Recent Posts

- Get HOMICIDE in four editions. Rated No.1 among The Five Best Crimes Biographies of All Time

- Peter Lance Biography

- HuffPost: DOJ report on MISSBURN case leaves out key detail: I.D. of the Mafia killer who broke the case for Hoover’s FBI

- On Halloween in 1994 CBS aired a new take on Orson Welles’ radio classic “War of The Worlds.” With 225,000+ views, it’s now become a YouTube cult favorite as well.

- Jason Leopold calls TRIPLE CROSS a “9/11 masterpiece”

Archives

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- March 2024

- January 2024

- November 2023

- June 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- September 2017

- June 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- June 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- March 2010

- August 2009

- November 2006

- November 2004

- October 2003

- September 2003

- February 2000

Categories

- 1000 Years for Revenge

- ABC's Path to 9/11 issue

- Ali Mohamed

- Ali Mohamed revelations

- Anwar al-Awlaki

- ARCHIVES

- awards

- bio

- BIOGRAPHY

- BOOK TV C-SPAN2

- BOOK WRITING

- BOOKS

- Colombo family "war"

- Commentary

- DUI investigation

- Emad Salem investigation

- FBI ORGANIZED CRIME

- Featured

- FICTION

- First Degree Burn

- Fitzgerald censorship attempt

- Fitzgerald censorship scandal

- Fox News

- Gotham City Insider

- Gregory Scarpa Jr.

- Gregory Scarpa Jr.

- Gregory Scarpa Sr.

- Harpercollins

- HUFFINGTON POST

- INVESTIGATIONS

- Khalid Shaikh Mohammed

- MAGAZINE ARTICLES

- Major Hasan Fort Hood massacre

- MEDIA COVERAGE

- Meier Kahane Assassination

- Meir Kahane assassination

- Murder Inc.

- Nat Geo whitewash

- NEWSPAPER REPORTING

- NOVELS

- Oklahoma City bombing

- Omar Abdel Rahman

- OPERATION ABLE DANGER

- POLICE CORRUPTION

- Produced

- R. Lindley DeVecchio

- Ramzi Yousef

- Ramzi Yousef sting 302's

- REPORTING & ANALYSIS

- RESEARCH

- Santa Barbara News-Press

- SCREENWRITING

- Stranger 456

- Stranger 456

- teleplays

- Tenacity Media

- Triple Cross

- Triple Cross

- TV NEWS COMMENTARY

- Uncategorized

- videos

- WIKIPEDIA

The real “smoking gun” in the 28 pages of the Joint Inquiry’s report now released: Prior to 9/11 The FBI didn’t focus on the Saudis

July 26th, 2016. By Peter Lance. On Monday, in a self-serving Op Ed page piece in the L.A. Times, the Saudi Ambassador to the U.S. declared, “There is no smoking gun in the 28 pages, let’s move on.”

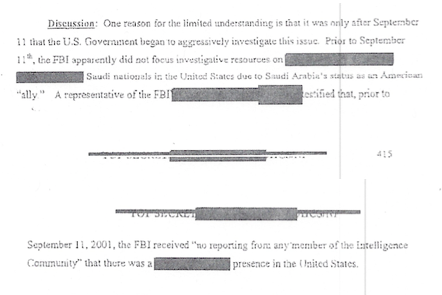

I beg to differ. Now that we have those 28 pages (from pp. 415 to 429) with limited redactions there is a stunning revelation at the bottom of page 415 – continuing to the top of the next page.

The REDACTED portion of the report was little more than a blank page and a series of lines. But the truth behind what was missing is another stunning indictment of the FBI. This is what it says:

“Discussion: One reason for the limited understanding is that it was only after September 11 that the U.S. Government began to aggressively investigate this issue. Prior to September 11th, the FBI apparently did not focus investigative resources on [REDACTED] Saudi nationals in the United States due to Saudi Arabia’s status as an American “ally.” A representative of the FBI [REDACTED] testified that, prior to September 11, 2001, the FBI received “no reporting from any member of the Intelligence Commity” that there was a [REDACTED] presence in the United States.”

Compare a screen capture from the REDACTED Report with one from the UN-REDACTED 28 pages just released:

THE COMPELLING EVIDENCE OF SAUDI INVOLVEMENT

The significance of this admission (which we’ve only now become aware of 13 1/2 years after publication of the Joint Inquiry’s report) is that post 9/11, congressional investigators couldn’t find the kind of “smoking gun” the Saudi Ambassador was talking about because before the attacks The Bureau never really looked for one.

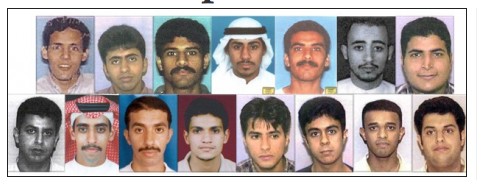

Fifteen of the nineteen 9/11 hijackers (above) were citizens of Saudi Arabia and as you’ll see below, in the first book in my HarperCollins 9/11 trilogy, “1000 Years For Revenge.” I reported on the multiple contacts prior to 9/11 between key Saudis with Khalid al-Midhar and Nawaf al-Hazmi, two of the “muscle hijackers” who flew AA Flight 77 in The Pentagon.

For C-Span2’s Book TV program at the time of “1000 Years” publication in 2003 I cited my findings on the short comings of The Joint Inquiry which preceded the 9/11 Commission.

This is an excerpt from The Introduction:

This book focuses exclusively on the Bureau, because it was the one U.S. law enforcement agency that had the responsibility and the knowledge to stop both attacks on the Trade Center. Further, the FBI’s continuing job of containing the al Qaeda threat is key to the safety of us all. An attempt by a Joint Senate-House Committee to get at the truth behind 9/11 was limited.

The committee, known as the Joint Inquiry, restricted itself to an examination of the intelligence agencies, and left out major components of the government, including the executive branch. After a ten-month investigation, the panel issued twenty-six pages of public “Findings” and “Recommendations,” but its full report remained classified for months. While citing multiple acts of negligence by the FBI and the CIA, the Joint Inquiry stopped far short of assessing blame.

Its report was considered so restrictive that Republican senator Richard Shelby, vice chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, issued his own eighty-four-page minority report chiding the overall Joint Inquiry for its failure to “assess accountability.” Later, senator Bob Graham, a Democratic candidate for president and a member of the original investigation, charged that the Bush administration’s apparent unwillingness to declassify the Joint Inquiry’s full report amounted to a “cover-up.”

By July 24, 2003 the Bush Administration had negotiated a deal with the Joint Inquiry staff to release a heavily redacted version of the 858-page report. But an entire 28-page section dealing with possible Saudi ties to the 9/11 attacks was left blank. One congressional investigator described the report as “a scathing indictment of the FBI…an agency that doesn’t have a clue about terrorism.”

The final report was so incomplete that its co-chairman, Rep. Porter J. Goss (DFL), admitted, “I can tell you right now that I don’t know exactly how the plot was hatched. I don’t know the where, the when, and the why and the who…. That’s after two years of trying.” In 2002, having given up hope that Congress would get to the truth, the organized families of 9/11 victims called for the creation of an independent panel, similar in scope to the Warren Commission established in 1964 to investigate the assassination of President Kennedy.

After fighting creation of such a commission through the summer and fall of 2002, the White House changed tack in September and agreed to an eleventh-hour compromise with Congress. The deal allowed President Bush to name the commission’s chairman and cochairman. But the first two appointees, Henry Kissinger and former Democratic senator George Mitchell, resigned within days, citing potential conflicts of interest.

In late December the president appointed former New Jersey governor Tom Kean to head the panel, but as hearings got under way in March 2003 serious questions were raised about whether the commission had the proper funding to do the job. Any probative findings relating to 9/11 aren’t expected until May 2004, and in its first report, issued July 8, 2003, commission staffers complained that their work was being hampered by the failure of the executive branch (particularly the Pentagon and the Justice Department) to quickly respond in the production of documents and testimony.”

In 2004 I devoted half of my second book, “Cover-Up” to a detailed examination of the failures of the 9/11 Commission. On April 15th, Mark Mazetti of The New York Times reported on threats being made by the Saudi Government to sell hundred of billions in U.S. assets if Congress went through with a bill to allow 9/11 victims families to sue The Kingdom.

As detailed throughout my third HarperCollins counter-terrorism book TRIPLE CROSS there were dozens of links between Saudi Arabia and the “planes as missiles” plot. Not only was Osama bin Laden, the son of a Saudi construction billionaire and all but 4 of the 19 hijackers from The Kingdom, but the most stunning revelation in terms of the FBI’s failure to stop the attacks involved al-Midhar and al-Hazmi.

What follows is an excerpt from that book reporting on the astonishing number of times these two Saudi terrorists showed up on the FBI and the CIA’s radar between January 2000 and 9/11.

The Muscle Hijackers and the One-Legged Terrorist

It’s not particularly surprising that the Operation Able Danger the DIA’s data sweep of open-source information would have picked up the soon-to-be muscle hijackers al-Midhar and al-Hazmi. Their visibility in the United States was so high in the eighteen months prior to their airborne assault on the Pentagon that the FBI’s failure to detect them seems to border on gross negligence—even with the CIA’s refusal to share the intel.

As early as 1999, while monitoring phone calls at the Sana’a Yemen safe house, the NSA picked up references to Khalid al-Midhar, Nawaf al-Hazmi, and his brother Salem, who would also become one of the suicide hijackers on 9/11.

The FBI knew about that safe house. In fact, the location was the result of a lead uncovered by their own criminal investigation of the East African embassy bombings. That wiretap of the home of Khalid al-Midhar’s brother-in-law led the CIA to monitor the summit in Kuala Lumpur, but even before that there is evidence that al-Midhar and al-Hazmi had entered the United States.

In a Pulitzer Prize-winning story for the Washington Post in late September 2001, Amy Goldstein reported that the two hijackers actually showed up at the Parkwood Apartments, a townhouse complex in San Diego, in late 1999.

This San Diego connection would prove key, because after the two hijackers returned to the United States and slipped past a Watch List in January 2000, they ended up living in rooms rented to them by a San Diego FBI informant. Tracked to the K.L. summit, al-Midhar’s passport was copied in Dubai and sent to the CIA’s Alec Station (where the FBI had an agent in residence).

Al-Midhar was later photographed at the K.L. summit by the Malaysian Special Branch. On January 8, when the conference ended, al-Midhar flew with al-Hazmi to Bangkok, Thailand—both of them using their own names on the flight manifests.

Sitting next to them in a three-seat configuration was Khallad bin Atash, the one-legged Saudi who had sent al-’Owali to his intended death in Nairobi. Atash had recently attempted to blow up an Aegis-class guided missile destroyer, the U.S.S. The Sullivans—a failed al Qaeda action that was a precursor to the Cole bombing.

At that point, the FBI was doing a full-court press on the embassy-bombing investigation. Al-’Owali’s tip on the Sana’a safe house had led to the discovery of al-Midhar by the Malaysians. The fact that Special Agent Frank Pellegrino of Squad I-49 had seen pictures of the K.L. summit meant that the Bureau was in the loop.

And yet following the January 8 flight, both the FBI and the CIA reportedly lost all three terrorists in the Thai capital. Worse, despite having identified al-Midhar as an al Qaeda associate, and realizing that he had a U.S. multientry visa, the CIA never added his name to the TIPOFF Watch List of some 70,000 suspected terrorists.

As such, using their own names, al-Midhar and al-Hazmi jetted from Bangkok to Los Angeles on January 15. There they were met by Omar al-Bayoumi, a Saudi suspected of being an intelligence officer, who had visited the Saudi consulate in Los Angeles the same day. Later, the two would-be hijackers moved to San Diego, where they lived openly for the next five months.

During that period, al-Bayoumi helped them get settled, finding them an apartment across from where he lived. It was later reported by Newsweek and the Washington Times that al-Bayoumi may have been the recipient of funds sent to his wife indirectly from Princess Haifa bin Faisal, wife of Saudi Arabia’s then-ambassador to the United States, Prince Bandar.

On historycommons.org, the brilliant 9/11 researcher Paul Thompson, author of The Terror Timeline, has summarized a series of news reports noting that Princess Haifa began sending cashier’s checks to Majeda Dwiekat, the Jordanian wife of one Osama Basnan, a Saudi living in San Diego. Basnan’s wife then reportedly signed many of the checks over to the wife of Omar al-Bayoumi.

Prince Bandar, who later stepped down as U.S. ambassador, emphatically denied any impropriety at the time the check scandal broke. But according to Thompson: Within days of bringing them from Los Angeles, al-Bayoumi throws a welcoming party that introduces them to the local Muslim community.

One associate later says that al-Bayoumi’s party “was a big deal…it meant that everyone accepted them without question.” He also introduces hijacker Hani Hanjour to the community a short time later. He tasks an acquaintance, Modhar Abdallah, to serve as their translator and help them get driver’s licenses, Social Security cards, information on flight schools and more.

The High Visibility of “Dumb and Dumber”

During their early months in San Diego, al-Midhar and al-Hazmi proved to be the antithesis of low-profile sleepers.

They took flight lessons at the Sorbi Flying Club, bought season passes to Sea World, played soccer in a local park, and interacted with many members of the Muslim community.

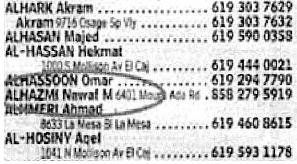

Al-Midhar bought a 1998 Toyota Corolla for $3,000 and registered it with the California DMV. After moving into a two-story town home at 6401 Mount Ada Road, al-Hazmi got a telephone.

He even had his full name listed in the phone directory:21 But the two Saudis showed little talent for flying.

Announcing that they wanted to learn to fly Boeing jumbo jets, they trained on twin-engine Cessnas, and demonstrated so little aptitude in the cockpit that their flight instructor, Rick Garza, nicknamed them “Dumb and Dumber.”

Throughout the spring and summer of 2000, the National Security Agency, which began monitoring al-Midhar’s brother-in-law’s home in Yemen in 1998, picked up multiple intercepts between San Diego and the safe house.

As it turned out, al-Midhar’s wife was about to give birth in the year 2000. But the NSA later claimed that it didn’t know that the calls from al-Midhar originated in the United States. It wasn’t until after 9/11 that the Feds realized that Ramzi bin al-Shibh, 9/11 “mastermind” Khalid Shaikh Mohammed’s number two on the entire planes-as-missiles operation, was al-Midhar’s cousin.

On June 3, 2000, lead hijacker Mohammed Atta arrived in the United States, and rented a room in Brooklyn, New York. He listed the same address in Hamburg, Germany: 54 Marienstrasse, where he’d been living with hijacker pilots al-Shehhi and Ziad Jarrah. In San Diego, neighbors of al-Midhar and al-Hazmi claimed that Atta and Hani Hanjour, the pilot of AA 77, visited them. There was a report that Hanjour actually roomed with them for a time, but didn’t stay.

On June 3, 2000, lead hijacker Mohammed Atta arrived in the United States, and rented a room in Brooklyn, New York. He listed the same address in Hamburg, Germany: 54 Marienstrasse, where he’d been living with hijacker pilots al-Shehhi and Ziad Jarrah. In San Diego, neighbors of al-Midhar and al-Hazmi claimed that Atta and Hani Hanjour, the pilot of AA 77, visited them. There was a report that Hanjour actually roomed with them for a time, but didn’t stay.

“Later, the Pentagon denied that the Able Danger data mining had uncovered Atta, al-Shehhi, and the two San Diego hijackers in early 2000,” says former Cong. Weldon. “But you can see how visible they were at this time. We’re not talking needles in haystacks here. With al-Midhar you’ve got a terrorist with known al Qaeda connections through the Yemeni safe house. Atta shows up in Brooklyn, and the LIWA people find out he’s linked to the Al Farooq Mosque, where the blind Sheikh ran his New York cell. This isn’t rocket science. These killers in our midst were highly visible.”

The FBI Blows Its Best Chance

Despite the FBI’s ongoing complaint that they were consistently blind-sided by the CIA on the presence of al-Midhar and al-Hazmi, both at the K.L. meeting and in their U.S. entry, the Bureau deserves equal criticism for its failure to locate the two muscle hijackers. Why? Because by the summer of 2000 they moved into the Lemon Grove section of San Diego, renting rooms from Abdussattar Shaykh, a local Muslim leader who was also an FBI informant.

The FBI later concludes that Shaykh is not involved in the 9/11 plot, but they have serious doubts about his credibility. After 9/11 he gives inaccurate information and has an “inconclusive” polygraph examination about his foreknowledge of the 9/11 attack. The FBI believes he has contact with hijacker Hani Hanjour, but he claims not to recognize him. There are other “significant inconsistencies” in Shaykh’s statements about the hijackers, including when he first met them and later meetings with them.

The 9/11 Congressional Inquiry later concludes that had the asset’s contacts with the hijackers been capitalized upon, it “would have given the San Diego FBI field office perhaps the U.S. intelligence community’s best chance to unravel the September 11 plot.”

After 9/11, when the Congressional Joint Inquiry discovered Shaykh’s identity and issued a subpoena for him to testify, Attorney General John Ashcroft refused to allow his agents to serve it. Sen. Bob Graham, the Democrat who cochaired the Joint Inquiry, used the term “cover up” to describe the stonewalling by Justice in refusing to disclose the depth of Shaykh’s apparent duplicity.

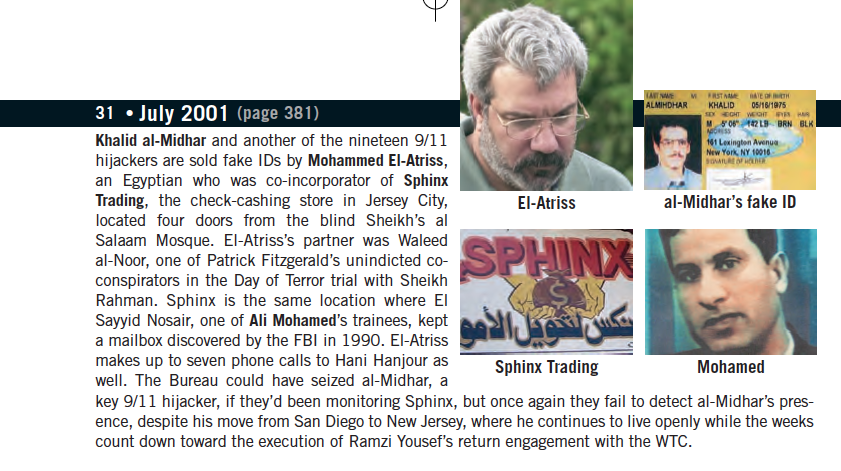

SPHINX TRADING THE LAST CHANCE

Recent Comments