HuffPost: DOJ report on MISSBURN case leaves out key detail: I.D. of the Mafia killer who broke the case for Hoover’s FBI

By Peter Lance June 27th, 2016. HuffingtonPost The NYT reported June 20th that a U.S. Justice Dept. inquiry into the notorious 1964 murders of civil rights workers, Goodman, Schwerner & Chaney, has ended with a 48 page report sent to Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood. Based on that report’s findings Hood has announced that the 52 year-old case is now closed.

By Peter Lance June 27th, 2016. HuffingtonPost The NYT reported June 20th that a U.S. Justice Dept. inquiry into the notorious 1964 murders of civil rights workers, Goodman, Schwerner & Chaney, has ended with a 48 page report sent to Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood. Based on that report’s findings Hood has announced that the 52 year-old case is now closed.

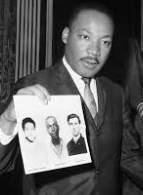

The three young voter registration volunteers were kidnapped and tortured by members of the Ku Klux Klan in Neshoba County during what civil rights leaders, including Dr. Martin Luther King, called “Freedom Summer.”

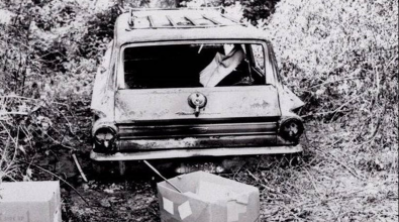

After they’d gone missing and their fire charred station wagon was later found, without their bodies, panic set in within the Justice Department of President Lyndon B. Johnson.

The incident inspired the film “Mississippi Burning,” which wrongly concluded that the case was solved after an African American FBI agent was sent to Mississippi and interrogated a KKK sympathizer.

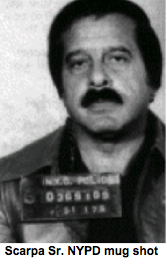

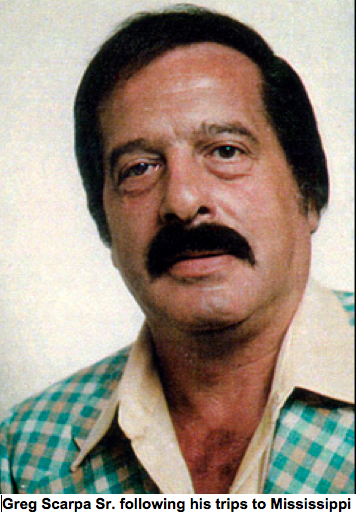

Although the DOJ report concludes that “The FBI conducted approximately 1000 interviews during the summer and fall of 1964,” the truth is that the location of the bodies, buried beneath an earthen damn on the farm of a Klan associate, was not discovered until after FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover sent Colombo crime family capo Greg “The Grim Reaper” Scarpa Sr. down to Mississippi.

As recounted in detail for the first time in my 2004 HarperCollins books “Cover Up” and in more depth in “Deal With The Devil,” ten years later, the Mafia hit man — who had for several years been a “Top Echelon Informant” on Hoover’s payroll — kidnapped and tortured a local KKK-friendly politician into giving up the burial site.

Only then did the Bureau break the case.

Only then did the Bureau break the case.

But there’s not a single word of Scarpa’s role in that 48 page report which merely notes that “in late July 1964, an informant provided accurate information about the location of the bodies.” The report otherwise attributes the discovery of the victims to good police work.

In fact, Scarpa’s Sr.’s mission in what the Bureau dubbed the MISSBURN case, was actually the first of two civil rights related interrogations he made at the behest of the FBI Director. The second took place in January, 1996 following the KKK firebombing and murder of civil rights leader Vernon Dahmer.

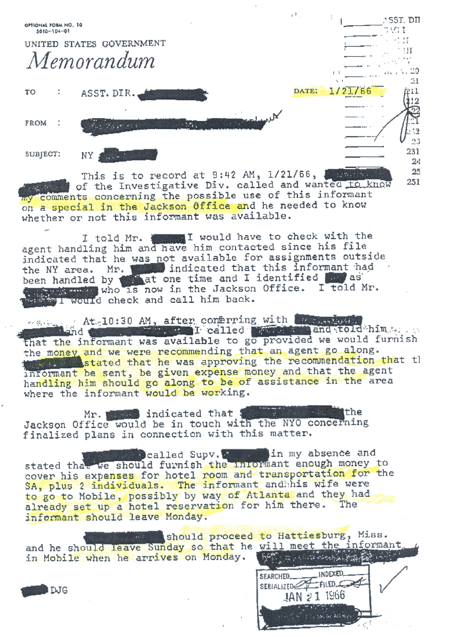

An Assistant FBI Director actually approved the mob killer’s assignment in a January 21, 1996 Airtel sent from Headquarters in D.C. to the Bureau’s New York Office (NYO). The heavily redacted communiqué, in which Scarpa Sr.’s name was blacked out, approved expense funds for him and his common law wife to travel via Mobile, Alabama to Hattiesburg, Mississippi where they would link with Special Agents.

Here now, is a full account of the way both investigations went down from “Deal With The Devil.”

THE SPECIAL GOES SOUTH

In the hot summer of 1964 J. Edgar Hoover finally found a way to make some affirmative use of the Brooklyn hit man who had been on his payroll for three years. “Whatever else he may have passed along in the way of intelligence,” says Fredric Dannen of the New Yorker, who wrote a definitive profile of Scarpa in 1996, “we know from the work he did in Mississippi that he became a clandestine asset for Hoover.”

The biggest crisis facing the U.S. Justice Department at that moment was the disappearance of three young civil rights workers, Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Chaney. Working for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), they had traveled to Philadelphia, Mississippi, on June 21 to look into the Klan’s role in burning the Mount Zion United Methodist Church and disappeared that same night.

When their empty, fire-charred Ford station wagon was recovered a short time later, the FBI was called in to work the case. Evidence later presented at trial would prove that the local KKK kleagle, or recruiter, Edgar Ray Killen, had conspired with a deputy sheriff to stop the young men for speeding as they left town.

After a chase, they were forced off the road, driven thirty-four miles to a remote location, and shot to death in cold blood. Their bodies were thrown back in the station wagon and driven to a nearby farm, where they were buried under fifteen feet of red clay in an earthen dam. The Ford was then set ablaze and dumped in a swamp.

As detailed in my second book, Cover Up, the disappearance immediately became a national news story and ignited a firestorm at the Justice Department. Dozens of special agents were rushed to Neshoba County to comb the fields, in what Hoover dubbed the MISSBURN case.

The 1988 film “Mississippi Burning” dramatized how the agents located the station wagon. But weeks passed without any significant leads as to the fate of the three young men, and the investigation stopped dead.

“Back then, a lot of local people feared the FBI as much as the Klan and nobody was talking,” says Judge W. O. Chet Dillard, who was a state’s attorney at the time. “Old J. Edgar figured that if he was gonna break that [case]— and he was hurtin’ to break it— he was gonna have to go to some extreme measures, and he did.”

Sometime in early August, the Bureau enlisted Gregory Scarpa, the FBI’s Top Echelon informant— who had earlier been contracted to murder the boss of his own crime family— to go to Mississippi to accomplish what the agents could not. “Hoover was getting a lot of pressure about the bodies not being found,” Scarpa’s common-law wife, Linda Schiro, testified in 2007.

“They approached Greg to go down to find the bodies.” Schiro, who was seventeen when she and Greg were flown to Mississippi, testified that they went to a hotel and found “eight or nine FBI agents” waiting. Scarpa winked at the agents, Schiro testified; then one of them knocked on the door of their room and gave him a gun.

“Greg changed his clothes,” she recalled, “and then he . . . left some money on the dresser. He told me that if he didn’t come back to . . . go back home.” An account of the story by Tom Robbins and Jerry Capeci, which ran in the New York Daily News in 1994, alleged that “Scarpa, according to sources, kidnapped [a] klansman” who had knowledge of the burial site.

“Armed with an FBI-supplied pistol,” they wrote, Scarpa “put the gun in his mouth and threatened to ‘blow his f—— ing brains out’ if he didn’t spill the beans.” But Judge Dillard, who interviewed a number of sources close to the incident, has a different account— one that suggests that Scarpa became even more violent during the interrogation.

“The man who knew where Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney were buried was the mayor of a local town,” says Dillard. “After Scarpa grabbed him, they took him to an undisclosed location, and while the agents waited outside, Scarpa started working on the guy.” Dillard says that Scarpa first “put a pistol to [the mayor’s] head, demanding to know where those boys were. But [he] told him a phony story.”

It was only after Scarpa checked with FBI agents to confirm the lie that he “put the barrel of the gun in the man’s mouth and cocked it.” Then, says Dillard, fearing reprisals from the Klan, the mayor lied a second time and the agents outside confirmed it.

INTERROGATION BY RAZOR BLADE

“It was at that point,” says Dillard, “that Scarpa took more drastic steps.” Taking out a straight razor, he proceeded to unzip the man’s fly. “He was threatenin’ to emasculate him,” says the judge. And that’s when the terrified Klansman “blurted out the location of the dam.”

Ten years later, a lawyer who represented Scarpa disclosed that Scarpa, the so-called Mad Hatter, had admitted to the interrogation by razor blade. On August 4, 1964, the three bodies were recovered six miles southwest of Philadelphia. Goodman and Schwerner had each been shot once in the head. Chaney, the black man in the group, was shot three times and beaten savagely.

Schiro testified that Scarpa later returned to the hotel and told her “they found the bodies.” She said that an FBI agent came by to retrieve the gun and handed Greg an envelope with cash “an inch thick” in a rubber band. After that, Schiro and Scarpa vacationed at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami Beach.

SCARPA’S NEXT MISSION

Eighteen months later, Hoover used Scarpa in a second mission to Mississippi to extract a confession from another KKK member.

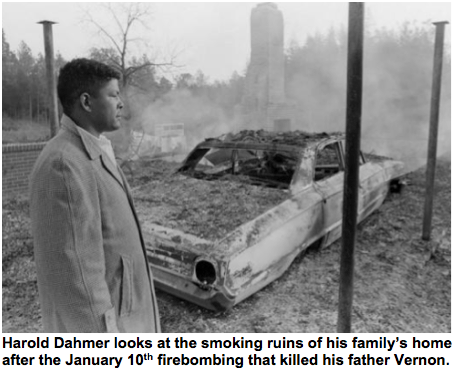

In early 1966, Vernon F. Dahmer, an African American farmer and shopkeeper who had allowed his store to be used for voter registration, was targeted by the Klan. On January 10, in the dead of night, two carloads of hooded Klansmen, brandishing shotguns and carrying twelve gallons of gasoline, showed up at Dahmer’s house and set it on fire.

In the blaze that followed, the fifty-eight-year-old Dahmer held the attackers at bay while his family escaped. But he later died in his wife’s arms.

As an indication of how seriously Washington reacted to the murder, President Johnson sent a telegram of condolence to the Dahmer family and Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach issued a statement vowing to devote “the full resources of the Justice Department to catching the perpetrators.”

“Once again, there were no leads,” says Judge Dillard. Eleven days after the firebombing, the FBI’s Criminal Investigative Division contacted the New York Office and dispatched Scarpa to Jackson, Mississippi, for what was referred to in an airtel as “a special.”

Again he abducted a Klan member and used violent means to extract a confession. But this time, according to Judge Dillard, he was directly “aided and abetted” in the kidnapping by an FBI agent.

The Bureau memo to the assistant director requesting Scarpa’s help also asked for “enough money to cover [informant’s] expenses for hotel room and transportation for the SA, plus two individuals,” indicating that Scarpa and Schiro were accompanied by an agent from New York.

The FBI’s preliminary investigation led to a Klan captain named Lawrence Byrd, who owned an appliance store called Byrd’s Radio and TV Service in nearby Laurel, Mississippi.

As Judge Dillard recounts in his book Clear Burning: Civil Rights, Civil Wrongs, Scarpa and another man, “wearing wigs,” arrived at the appliance store just before closing on January 26, 1966.

“Scarpa and this agent bought a TV set from Lawrence,” says Dillard. “They said they were going to pull around back and asked if he could bring it out to their car. When he came out they grabbed him, threw a blanket over him, and shoved him in the vehicle.”

At that point, says Dillard, they drove to Camp Shelby, a military base in nearby Hattiesburg, where the interrogation took place. There, according to Dillard, who later interviewed Byrd in the Jones County Hospital, Scarpa proceeded to “beat him within an inch of his life. . . .

They threatened to string him up and leave him out there naked in the winter, where the animals could get at him,” says the judge. “Lawrence was a tough guy— a big, raw-boned country boy— but he was beat up so bad he was never the same after that,” Dillard told writer Fredric Dannen.

In fact, an FBI 302 memo dated February 2, 1966, suggests that Byrd was so terrified that he refused to reveal the details to the FBI agents who later questioned him, stating only that he had been the victim of “an armed robbery by unknown persons.”

The memo insisted that Byrd was “still in a state of semi-shock.” On March 2, 1966, Byrd signed a twenty-two-page confession to his participation in the Dahmer firebombing, implicating himself and seven other Klansmen. Linda Schiro later testified that Greg “got the guy from the Ku Klux Klan . . . to admit that he was [the] one who burnt that house down.”

In 1998, Samuel K. Bowers, the imperial wizard of a Mississippi KKK faction, was found guilty in the Dahmer firebombing murder. 26 The FBI later attributed nine murders and three hundred beatings, arsons, and bombings to Bowers’s klavern, or local unit, of the Ku Klux Klan’s White Knights.

He had previously served six years for the Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney killings, which were executed by the same Klan cell. Edgar Ray Killen, who was the actual ringleader in the MISSBURN murders, escaped conviction in 1967 after an all-white jury deadlocked. But in 2005, when new evidence was developed, he was found guilty of manslaughter.

At the age of eighty, Killen was sentenced to sixty years in prison. Then, in February 2009, Killen filed suit against the FBI, arguing that his civil rights had been violated— because of the Bureau’s use of Gregory Scarpa Sr., a Mafia killer, in solving the Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney kidnap-murders.

“The information that Scarpa obtained by use of torture violates Killen’s civil rights . . . [his] right to due process [and] the right to confront witnesses,” his lawyer said.

One former DEA special agent, Mike Levine, was astonished by Hoover’s decision to enlist a known Mafia strongman to further the cause of justice.

“Here the FBI uses a member of a violent secret society— La Cosa Nostra— to travel down to Mississippi on multiple missions to torture confessions out of two guys who were also members of a violent secret society— the Klan. Since when does the federal government have to stoop to levels like that to make cases? This was during the same era when the CIA was trying to get mob guys to kill Castro.”

As Levine notes, such behavior on the Feds’ part was roundly denounced during congressional hearings in the 1970s, 31 and the popular assumption was that it stopped. “But the fact that the Bureau continued to use a multiple murderer like Scarpa right up into the early 1990s,” says Levine, “just proves that it didn’t.”

Anthony Villano, Scarpa’s control agent from 1967 to 1973, also disapproved. In his 1977 memoir, Brick Agent, Villano wrote, “When I heard the story [about Mississippi] and confirmed it was [Scarpa] I was ashamed that the people I worked for had to go outside the Bureau to find someone to perform their dirty work. An agent could have done what [Scarpa] did, but using him, of course, reduced the potential for scandal about the behavior of agents on the job.”

THE FBI’S VERSION OF THE CASE

On it’s official website the Bureau describes the Dahmer investigation and subsequent arrests of Bowers and other Klansman this way:

Let the investigation begin. At 3:15 that morning, an FBI agent in Meridian, Mississippi, got a phone call about the attack and quickly opened an investigation in concert with local authorities. Nearly 20 FBI agents began canvassing the area.

They interviewed local Klansmen and Klan informants and gathered 120 pieces of evidence—including tire tracks and shell casings—that were analyzed by the FBI Lab in Washington. They also learned that the day before the attack, a Sunday radio program had announced that Dahmer would help blacks register to vote by making his country store one of the few spots in the area where they could pay their $2 poll tax.

Our agents soon identified a number of suspects and compiled a 1,100 page report outlining the case. On March 27, a complaint was filed against fourteen men. Thirteen were arrested by the next day. The 14th—Sam Bowers, the Imperial Wizard of the Mississippi White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, who had ordered the attack—turned himself in several days later.

As with the FBI’s 48 page report on the MISSBURN investigation there is no reference to the Mafia killer whom J. Edgar Hoover flew down to Mississippi twice to get “justice” for The Bureau.

CONFLICTING ACCOUNTS

At least three published descriptions of Scarpa’s work for the FBI in Mississippi commingle the 1964 MISSBURN and 1966 Dahmer interrogations into one mission.

In Mafia Son, a 2009 biography of Scarpa’s son Gregory Jr., author Sandra Harmon writes that in 1964, after receiving the gun from the FBI agent in the Mississippi hotel, “Greg Sr. drove a rented car to a small appliance store owned by a Klansman named Byrd.” In Harmon’s account, Scarpa drove “south for several hours” tailed by “a second car filled with federal agents”; rather than Camp Shelby, she gives the location of Byrd’s interrogation as “a lonely country cabin tucked deep in the Mississippi woods.”

Supplying what purports to be actual dialogue from the incident, Harmon then mixes details from Scarpa’s interrogation of the KKK mayor from the MISSBURN case and appliance store owner Byrd from the Dahmer case. She even furnishes details, purportedly from Byrd’s mouth, about the abduction of Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney—an incident that took place eighteen months earlier.

Jerry Capeci, a respected reporter on organized crime whose “Gang Land” column appeared for many years in the New York Daily News and the New York Sun, is credited with being the first reporter to break the Scarpa connection to the MISSBURN story in that June 21, 1994, Daily News article he wrote with Tom Robbins. But in a subsequent column published in the Sun on January 12, 2006, Capeci also combines details of Scarpa’s involvement in the Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney investigation with the mobster’s subsequent role in the Vernon Dahmer murder.

In that Sun column, Capeci writes that Scarpa was flown to Miami in the 1964 MISSBURN case before he went to Mississippi, then cites details that could only have occurred in 1966 in connection with the Dahmer firebombing investigation, which involved TV and appliance dealer Lawrence Byrd: “Scarpa stopped at his store,” writes Capeci, “said he was new in town, and put down a deposit on a television set. He promised to pick it up by closing time. When he returned, he got the merchant to help him carry the TV to his car, slapped him over the head with a pipe, tied him up, and threw him in the trunk of the car. He drove to a prearranged location, a shanty deep among tall loblolly pines where FBI agents were hidden outside.”

Like Sandra Harmon in Mafia Son, Capeci includes verbatim dialogue that purports to be from Scarpa’s interrogation of Byrd: “What happened to the three kids?” he has Scarpa saying, adding the line he included in his 1994 story with Robbins: “Tell me the f——ing truth or I’ll blow your f——ing brains out.”

Similarly, in a January 17, 2006, piece for the Village Voice, where he worked after leaving the Daily News, Robbins writes in reference to the MISSBURN incident that Scarpa “walked into a Philadelphia appliance shop owned by a Klan-tied merchant whom the FBI believed knew the fate of the missing civil rights workers. Scarpa convinced the man he had just come to town and wanted a new TV set. But when he returned to pick it up that evening, he slugged the merchant, tossed him in the trunk of a car, and drove him to a remote spot where bureau agents were standing guard.”

What makes Robbins’s combination of the 1964 and 1966 Scarpa missions interesting is the fact that in his Village Voice piece he actually cites the January 21, 1966, FBI memo on Scarpa’s recruitment in the Dahmer case. “An agent is seeking permission to use Scarpa ‘on a special’ again in Mississippi,” writes Robbins—proof that he knew of two missions, not just the one he and Capeci reported on in 1994—the MISSBURN initiative that they confused with the Dahmer case.

These mistakes by Robbins and Capeci are worth noting because it was an interview they did with Linda Schiro in 1997 that led to the dramatic dismissal of murder charges against Scarpa’s fourth major FBI contacting agent, Lin DeVecchio, in 2007. We’ll examine the details of that case later.

But whatever conflicts may exist in published accounts of Scarpa’s story, one thing is clear: He was a ruthless gangster with little regard for human life and we can now say with certainty that J. Edgar Hoover himself understood that. Nonetheless, the Director continued to encourage the Bureau’s use of “34” as an informant.

Testifying in 1986 before the President’s Commission on Organized Crime, Marty Light, one of Scarpa’s former lawyers, reflected: “Greg was the type of guy who would arrange to have dinner with you. He would laugh, make jokes, ask about your family and then when dessert came, he would just whack you right on the spot.” Years later, Scarpa crew member Joseph Ambrosino was asked at trial why they called his boss the Grim Reaper. “He was crazy,” Ambrosino, replied. “He killed a lot. He was nuts.”

Recent Comments