HuffPost: Blowback. The potential lethal fallout from the CIA-Saudi deal to arm Syrian rebels

By Peter Lance Huffington Post The New York Times reported Sunday on the history behind the White House’s secret 2013 authorization for the CIA to arm Syrian rebels with the clandestine help of Saudi Arabia. In intelligence circles they call it “blowback,” a deadly unintended consequence of a covert op and the current initiative should give us pause.

By Peter Lance Huffington Post The New York Times reported Sunday on the history behind the White House’s secret 2013 authorization for the CIA to arm Syrian rebels with the clandestine help of Saudi Arabia. In intelligence circles they call it “blowback,” a deadly unintended consequence of a covert op and the current initiative should give us pause.

Why? Because in the endless revolving door of espionage, leading to war, leading to collateral damage, few examples of blowback, underscore the lethal risks of clandestine partnerships more than the Agency’s use of the Saudis to fund the Mujahadeen rebels during the Afghan war.

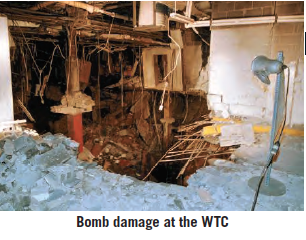

It was a operation begun in the late 1980’s with the best of intentions: to thwart what Ronald Reagan called “The Evil Empire.” But as I’ve documented in four books over the last ten years, that secret funding of “The Muj” can be linked, directly, not only to the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center, but the ultimate destruction of The Towers on 9/11 by a cell funded by the principal beneficiary of the secret Saudi-CIA aid: Osama bin Laden.

If we’re to accept George Santayana’s dictum that those who forget the past are “condemned to repeat it,” the U.S. should be extremely cautious about who we’re arming and the deadly long term effects that could easily blowback to the American homeland.

What follows is excerpt from my first HarperCollins book, “1000 Years For Revenge.”

The U.S. price tag for the covert aid reportedly reached $3 billion. As many as twenty-five thousand young jihadis poured in from around the globe to fight and train in guerrilla tactics.

Though later dubbed “Afghan Arabs,” there were blue-eyed Chechens, black South Africans and Filipinos along with Kurds, Yemenis, Uzbekis and Saudis.

They studied bomb making, hijacking and other covert ops. The difference was that veterans of the anti-fascist campaign in the 1930’s like Hemingway later went to Paris to write books, and in this case, the well-trained post-war jihadis decided to focus their attention on the West and blow things up.

During this period, intelligence officials believe that Ramzi Yousef (architect of the ’93 WTC bombing and the 9/11 “planes as missiles” plot) first connected with three men who would one day carve their names in the history of Islamic terror. Abdurajak Janjalani was a Libyan-trained Filipino whose nom de guerre was Abu Sayyaf.

During this period, intelligence officials believe that Ramzi Yousef (architect of the ’93 WTC bombing and the 9/11 “planes as missiles” plot) first connected with three men who would one day carve their names in the history of Islamic terror. Abdurajak Janjalani was a Libyan-trained Filipino whose nom de guerre was Abu Sayyaf.

Mahmud Abouhalima was a six-foot-two redheaded Egyptian who did two tours in Afghanistan. Dubbed “the Red,” Abouhalima, was a disciple of Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, leader of the al Gamm’a Islamiya, or IG, one of the most virulent Egyptian terror groups.

These Afghan connections would prove crucial to Yousef as his career advanced. Abouhalima, would be one of his key operatives as he built the original World Trade Center bomb in 1992. Sheikh Rahman would be at the heart of Yousef’s bombing cell, based in Jersey City. Later, the Abu Sayyaf terror group named for Janjalani, would provide Yousef the infrastructure he needed when he plotted the 9/11 attacks in Manila in 1995.

But the bomb maker’s chief sponsor over the years—the man who funded and guided him—was Osama bin Laden, the seventeenth son of a Saudi construction billionaire. Beginning in the early 1990s, Yousef emerged as the point man for bin Laden’s worldwide terror network. Al Qaeda, meaning “the base,” sprang directly from a string of refugee centers set up as fund-raising conduits for the Mujahadeen rebels. In short, when probing the origin of the 9/11 attacks, all roads lead back to Afghanistan and Peshawar in the final days of the Soviet invasion.

AL QAEDA’S NEW YORK CELL

By the late 1980s, New York City was beginning to feel the early stirrings of a clandestine movement born out of a war half a world away. An estimated fourteen thousand jihadis had dispersed after the Russians abandoned Afghanistan in 1989 and untold numbers began to settle in New York and New Jersey. Ali Mohammed, the secretive ex-Egyptian Army officer who conducted paramilitary training of the cell at a shooting range in Calverton, Long Island, later told federal investigators that al Qaeda sleeper agents called “submarines” were burrowing deep into U.S. cities.

When the Afghan war ended, “we got the hell out of there,” said Milt Bearden, the former CIA station chief in Islamabad. “Afghanistan was off the front burner.” But America’s sudden abandonment of the region, a theater of ops it had invested so heavily in, was a strategic mistake of historic proportions.

When the Afghan war ended, “we got the hell out of there,” said Milt Bearden, the former CIA station chief in Islamabad. “Afghanistan was off the front burner.” But America’s sudden abandonment of the region, a theater of ops it had invested so heavily in, was a strategic mistake of historic proportions.

A few months after the World Trade Center bombing in 1993, Jack Blum, the former special counsel to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, drew a direct link between the devastation below the Trade Towers and U.S. support for the “Afghan Arabs” in the war against the Soviets.

“Large chunks of our Government don’t want to look at the disposal problem at the end of our war,” said Blum. “Nobody wants to acknowledge this is our glorious victory in Afghanistan coming home to bite us.” At that moment, the man with the sharpest set of teeth was preaching from a mosque located on the third floor above a toy store in Jersey City.

Born in 1938 near the Nile Delta, Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman lost his sight as an infant. By the age of eleven, driven by a relative who forced him to get up at 4:00 a.m. and study Islamic scripture in Braille, the young Omar had memorized the entire Koran. He went on to distinguish himself at Cairo’s Al Azhar, the oldest university in the Islamic world, where he earned a degree in Quaranic studies in 1972.

Abdel Rahman preached that Muslims had a duty to kill political leaders who didn’t adhere strictly to the Sharia, the holy law of Islam. He was jailed for nine months in the notorious Qala prison, and reportedly subjected to brutal torture, which only steeled his resolve.

In 1988, having been jailed, tried, and acquitted once again for his alleged role in a wave of terror against Egyptian Coptic Christians, the Sheikh made his way to Peshawar, Pakistan, near the Afghan border.

It was the height of the anti-Soviet war, and Peshawar, a kind of Wild West town near the Afghan frontier, was the staging area for the U.S. supply operation. Here the blind Sheikh soon became allied with the head of the largest Afghan Mujahadeen rebel faction backed by the CIA.

As billions of dollars poured in from the U.S. and the Saudis, the Sheikh reconnected with another former Al-Azhar instructor, Sheikh Abdullah Azzam. A Palestinian Ph.D., Azzam was one of the founding fathers of the modern radical Islamic jihad. His slogan was “Jihad and the rifle alone: no negotiations, no conferences, no dialogues.”

As billions of dollars poured in from the U.S. and the Saudis, the Sheikh reconnected with another former Al-Azhar instructor, Sheikh Abdullah Azzam. A Palestinian Ph.D., Azzam was one of the founding fathers of the modern radical Islamic jihad. His slogan was “Jihad and the rifle alone: no negotiations, no conferences, no dialogues.”

Terrorism analyst Steven Emerson has said that Azzam “is more responsible than any Arab figure in modern history for galvanizing the Muslim masses to wage an international holy war against all infidels and non believers.”

Exhorting Muslims to “unsheathe [their] sword[s]” against the perceived enemies of Islam, Azzam crossed the world from 1985 to 1989. He visited dozens of U.S. cities, and began setting up a network of offices designed as recruiting posts and fundraising centers for the Mujahadeen in their battle with the Soviets. Informally they were known as NGOs — non-governmental organizations — entities that purportedly raised money for charitable purposes.

The first center, established in the early 1980s in Peshawar, was called Alkifah. Over the next decade, Azzam set up branches at mosques in the U.S., the U.K. France, Germany, Norway, and throughout the Mideast. The network was formally known as the Services Office for the Mujahadeen, or Makhtab al-Khidimat (MAK).

FROM AFGHANISTAN TO BROOKLYN

The flagship Alkifah center in the U.S. was established on the ground floor of the El Farooq mosque in Brooklyn. A counterpart was created at the Islamic Center in Tucson. Soon Azzam had opened similar offices in Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and thirty other U.S. cities. During the late 1980s the network raised millions each year for the Afghan struggle.

All of this would come to have deadly importance in 1989, when the Services Office was taken over by Osama bin Laden and morphed into his terror network called al Qaeda.

It was Azzam who introduced the blind Sheikh to the young Saudi billionaire. At the age of twenty-two, bin Laden had arrived in Peshawar in the mid 1980s with a military transport plane full of bulldozers and equipment from his family construction conglomerate, the Bin Laden Group. Dubbed “the Contractor,” bin Laden quickly used the equipment to build roads, storage depots, and tunnels for the Mujahadeen then battling the Soviets. Before long, Azzam convinced bin Laden to help fund his worldwide Services Office network of NGOs.

During the late 1980s, as the Afghan war waged on and the cash poured in, bin Laden became devoted to Azzam. But soon after the Soviets were defeated, a conflict developed between Azzam and bin Laden over the best use of the fortune in aid that still flowed through the centers of the MAK. Azzam wanted the money to help install a pure Islamic government in Afghanistan, in a revolution akin to the one that had swept Iran in 1979.

During the late 1980s, as the Afghan war waged on and the cash poured in, bin Laden became devoted to Azzam. But soon after the Soviets were defeated, a conflict developed between Azzam and bin Laden over the best use of the fortune in aid that still flowed through the centers of the MAK. Azzam wanted the money to help install a pure Islamic government in Afghanistan, in a revolution akin to the one that had swept Iran in 1979.

But bin Laden’s plan was much more ambitious. He wanted the Services Office money directed to a worldwide “global jihad,” that would carry the war to secular Islamic nations and the West. Like the blind Sheikh, bin Laden was a puritanical disciple of Taymiyah and Qutb, who saw America in particular as a “satanic state.”

Azzam argued openly and bitterly with the blind Sheikh who backed bin Laden along with two other Egyptians: Dr. Ayman Al Zawahiri, head of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ), and Mohammed Atef, an ex-Cairo police official who became bin Laden’s right–hand man.

LIKE A MAFIA RUBOUT

The power struggle for control of the Services Office rivaled the internecine warfare of two Mafia families. Finally, after a violent triple homicide, the Egyptian-backed bin Laden bloc prevailed.

On November 24, 1989, Azzam and his two sons were killed by a car bomb in Peshawar, Pakistan, as they drove to juma (Friday prayers). The murders remain unsolved, and although he expressed public grief at their deaths, some U.S. intelligence officials believe that Osama bin Laden himself gave the order for the hit.

At that moment, one of Azzam’s most productive U.S. based Services Office outposts was the Alkifah Center in Brooklyn. And as it turned out, the FBI had it under surveillance as far back as 1989, when George Herbert Walker Bush was in the White House.

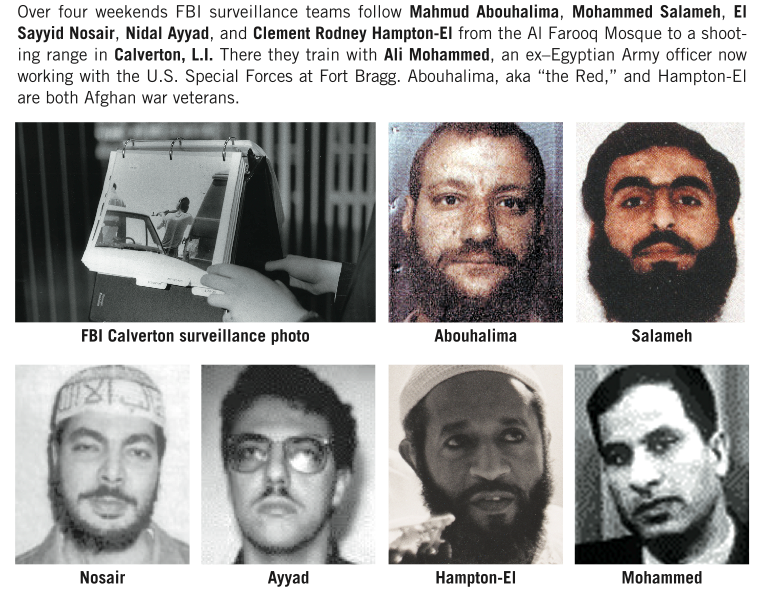

On four weekends in July, the FBI’s Special Operations Group (SOG) followed a group of “ME’s” — or “middle eastern men,” in Bureau speak — from that mosque to the Calverton shooting range in eastern, Long Island.

Of the “ME’s” photographed by the FBI that July, three —Abouhalima, Salameh, and Ayyad— would later be convicted as Ramzi Yousef’s co-conspirators in the World Trade Center bombing and Nosair, would soon use his Calverton .347 magnum training to ignite the first act of al Qaeda violence on American soil, the murder of right-wing rabbi Meir Kahane.

On his return to Egypt in 1990, Sheikh Abdel Rahman was placed under house arrest, but he escaped when his followers used a double to pose for him. By that summer, Rahman had made his way to Sudan. There, even though he’d been on a U.S. terrorism Watch List for three years, the Sheikh was granted a visa to enter America. This was another blunder on the part of U.S. intelligence that became a significant dot on the chart.

PAYBACK FOR THE BLIND SHEIKH’S HELP WITH THE CIA-SAUDI FUNDING OF THE MUJAHADEEN

Later the CIA would try to blame his admission on a corrupt case officer who helped Abdel Rahman’s lawyer obtain illegal U.S. visas for his clients. But the State Department later determined that although he was on the list of “undesirables,” the Sheikh got three sanctioned visas from CIA agents posing as State Department officials at the U.S. Embassy in Khartoum.

Many intelligence analysts believe that Abdel Rahman’s entry was payback by the Agency for his help in the CIA’s support of the Afghan “freedom fighters.” At the time, no one in U.S. intelligence circles or seemed to notice that the chief Afghan warlord, backed by the CIA, was denouncing the U.S. with the same level of hatred he’d shown toward the USSR.

The night he flew into JFK in July of 1990, Omar Abdel Rahman was picked up by Mahmud Abouhalima, the redheaded Egyptian who had fired AK-47s at Calverton. This was the same man who would drive the aborted getaway cab on the night of Kahane’s murder four months later and later be convicted in Ramzi Yousef’s February 26th, 1993 bombing of the WTC which killed six and injured a thousand.

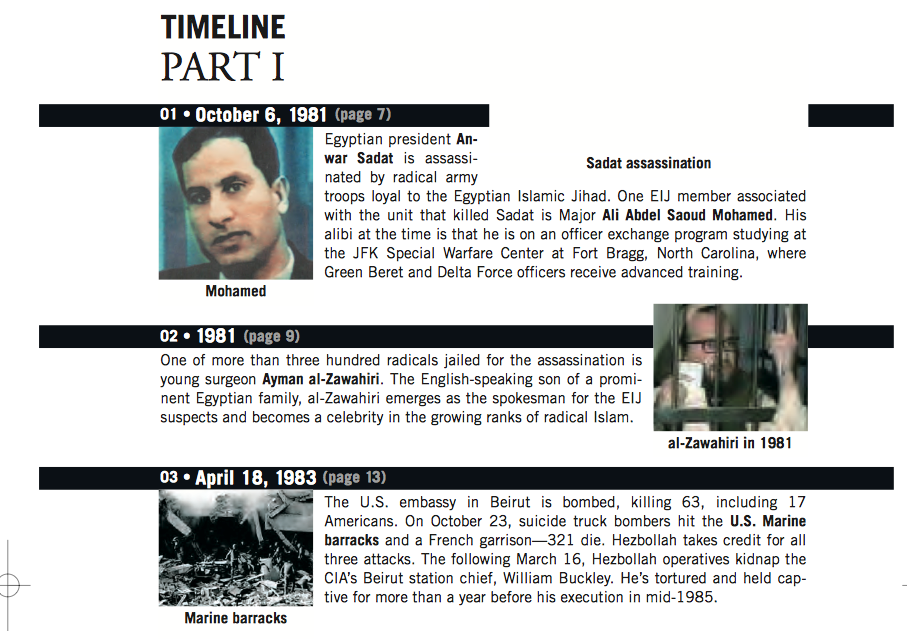

In my third HarperCollins book “Triple Cross” all of the dots in this daisy chain of terror were connected: from the 1983 murder of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, up through the covert CIA-Saudi funding of the Mujahjadeen, through bin Laden’s takeover of Azzam’s MAK network and it’s deadly morphing into al Qaeda, through the terror network’s funding of both attacks on the WTC.

For the 32 page illustrated TIMELINE click on the image below. As the French say, in their own more subtle variation on Santanya’s warning: plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose: the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Recent Comments