Recent Posts

- Get HOMICIDE in four editions. Rated No.1 among The Five Best Crimes Biographies of All Time

- Peter Lance Biography

- HuffPost: DOJ report on MISSBURN case leaves out key detail: I.D. of the Mafia killer who broke the case for Hoover’s FBI

- On Halloween in 1994 CBS aired a new take on Orson Welles’ radio classic “War of The Worlds.” With 225,000+ views, it’s now become a YouTube cult favorite as well.

- Jason Leopold calls TRIPLE CROSS a “9/11 masterpiece”

Archives

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- March 2024

- January 2024

- November 2023

- June 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- September 2017

- June 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- June 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- March 2010

- August 2009

- November 2006

- November 2004

- October 2003

- September 2003

- February 2000

Categories

- 1000 Years for Revenge

- ABC's Path to 9/11 issue

- Ali Mohamed

- Ali Mohamed revelations

- Anwar al-Awlaki

- ARCHIVES

- awards

- bio

- BIOGRAPHY

- BOOK TV C-SPAN2

- BOOK WRITING

- BOOKS

- Colombo family "war"

- Commentary

- DUI investigation

- Emad Salem investigation

- FBI ORGANIZED CRIME

- Featured

- FICTION

- First Degree Burn

- Fitzgerald censorship attempt

- Fitzgerald censorship scandal

- Fox News

- Gotham City Insider

- Gregory Scarpa Jr.

- Gregory Scarpa Jr.

- Gregory Scarpa Sr.

- Harpercollins

- HUFFINGTON POST

- INVESTIGATIONS

- Khalid Shaikh Mohammed

- MAGAZINE ARTICLES

- Major Hasan Fort Hood massacre

- MEDIA COVERAGE

- Meier Kahane Assassination

- Meir Kahane assassination

- Murder Inc.

- Nat Geo whitewash

- NEWSPAPER REPORTING

- NOVELS

- Oklahoma City bombing

- Omar Abdel Rahman

- OPERATION ABLE DANGER

- POLICE CORRUPTION

- Produced

- R. Lindley DeVecchio

- Ramzi Yousef

- Ramzi Yousef sting 302's

- REPORTING & ANALYSIS

- RESEARCH

- Santa Barbara News-Press

- SCREENWRITING

- Stranger 456

- Stranger 456

- teleplays

- Tenacity Media

- Triple Cross

- Triple Cross

- TV NEWS COMMENTARY

- Uncategorized

- videos

- WIKIPEDIA

25 years later: Qaeda leader killed in Pakistan had links to blind Sheikh and Brooklyn mosque where FBI tracked terrorists in 1989

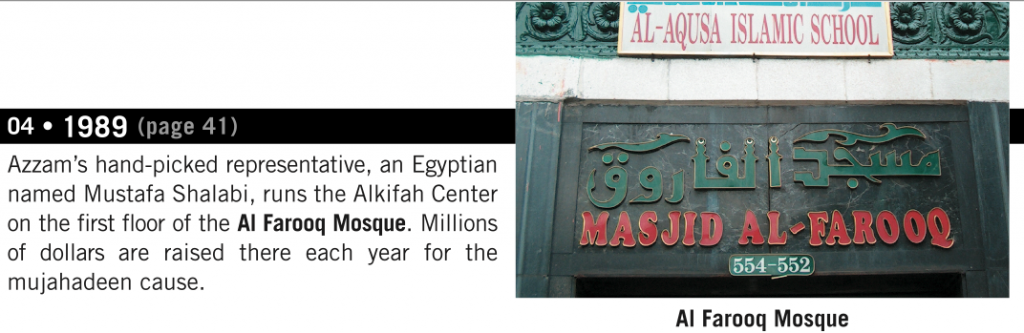

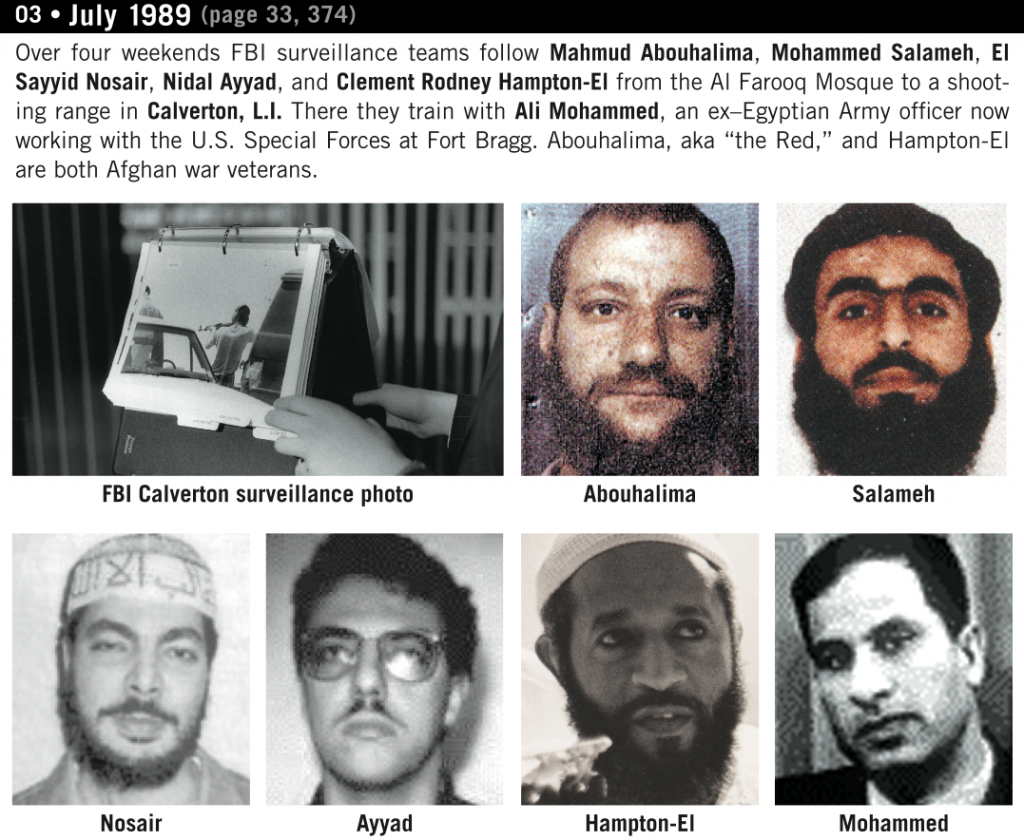

December 21st, 2014. By Peter Lance. Note to December 8th Miami Herald story. Twenty-five years after the FBI’s elite Special Operations Group followed a group of ME’s (Middle Eastern Men) from the al-Farooq mosque on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn to a shooting range on eastern Long Island where they took dozens of surveillance photos, Adnan El Shukrijumah, a senior al Qaeda leader suspected in his links to the 9/11 hijackers was killed December 7th in Pakistan. See story by Alfonso Chardy and Jay Weaver in The Miami Herald below. El Shukrijumah’s father Gulshair, served as prayer leader at the al Farooq mosque, which I proved in my first book for HarperCollins, “1000 Years For Revenge,” was a literal al Qaeda clubhouse.

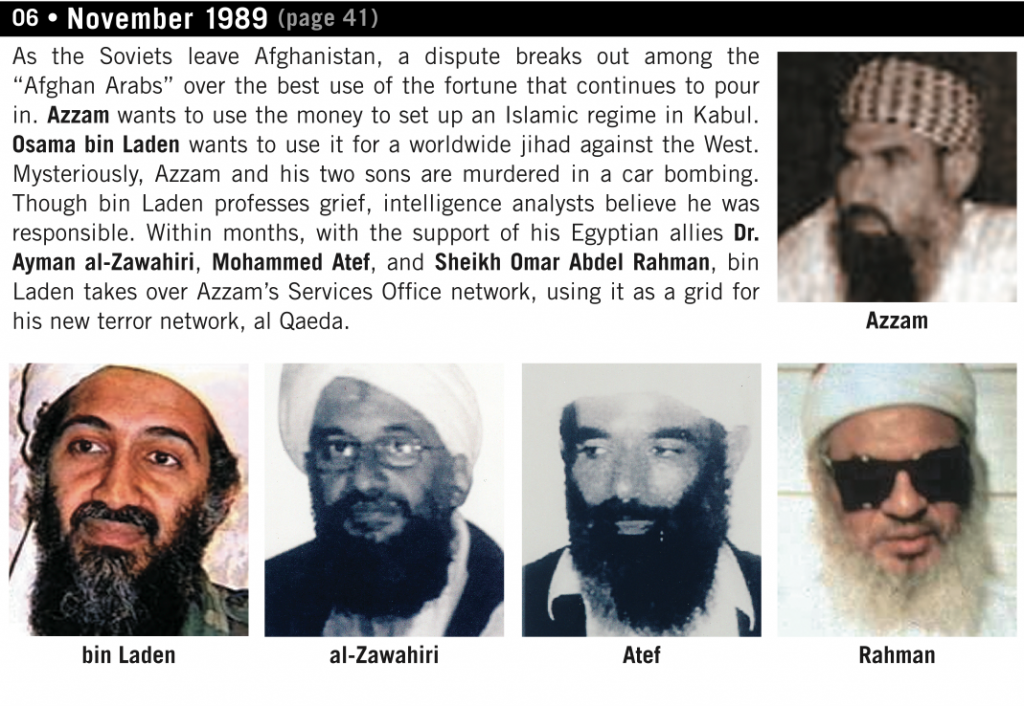

It was was the New York hub of the Maktab al-Khidamat, a network that collected millions of dollars a year for the Mujahadeen fighting in Afghanistan. Set up by Palestinian scholar Abdullah Azzam, the MAK, as it was known, was soon taken over by Osama bin laden, Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri and blind Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman in a jihadi coup d’etat in November of 1989.

It was was the New York hub of the Maktab al-Khidamat, a network that collected millions of dollars a year for the Mujahadeen fighting in Afghanistan. Set up by Palestinian scholar Abdullah Azzam, the MAK, as it was known, was soon taken over by Osama bin laden, Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri and blind Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman in a jihadi coup d’etat in November of 1989.

All of this is documented in the 32 page illustrated timeline from my book, published in 2003. If you scroll through that timeline you’ll understand how Adnan El Shukrijumah’s links through his father to the blind Sheikh help to connect new dots in the story of the FBI’s negligence on the road to 9/11.

As I reported in “1000 Years,” and later in my book “Triple Cross,” of the men photographed by the Bureau in the summer of ’89 at that Calverton, L.I. shooting range, three were convicted in the plot to bomb the World Trade Center in 1993, one was convicted in “The Day of Terror Plot” to blow up the bridges and tunnels into Manhattan and one killed Rabbi Meir Kahane which I contend was the first blood spilled by al Qaeda on U.S. soil.

Further, their leader, Ali Mohamed, the al Qaeda spy who trained bin Laden’s personal body guard while acting as an FBI informant, went on to plan the East African Embassy bombings in 1998. See illustrated timeline from “Triple Cross.”

BUREAU DROPS THE PROBE

But for reasons the FBI never explained, they ended their surveillance of the mosque and those cell members who went on to commit multiple acts of terror which took hundreds of lives over the next nine years.

In 2010 after I’d connected with Emad Salem, the courageous ex-Egyptian army officer who infiltrated the blind Sheikh’s cell for the FBI, we worked with decorated NYPD Detective James Moss of Brooklyn South Homicide to solve the 19 year-old cold case murder of Mustafah Shalabi, who ran the MAK (AlKifah) Center at the al Farooq mosque. That story is documented in this piece for PLAYBOY, “The Spy Who Came In For The Heat.”

In 2010 after I’d connected with Emad Salem, the courageous ex-Egyptian army officer who infiltrated the blind Sheikh’s cell for the FBI, we worked with decorated NYPD Detective James Moss of Brooklyn South Homicide to solve the 19 year-old cold case murder of Mustafah Shalabi, who ran the MAK (AlKifah) Center at the al Farooq mosque. That story is documented in this piece for PLAYBOY, “The Spy Who Came In For The Heat.”

As far back as March, 2003 The New York Times described the al-Farooq as a “Terror Icon,” after a federal lawsuit cited links between the mosque, a number of Brooklyn businessmen and a Yemeni cleric the Feds said had sent more than $20 million to al Qaeda.

THE NYPD’S ‘MOSQUE CRAWLERS”

But in response to that potential threat the NYPD began a domestic surveillance program unlike anything conducted by a local police department in U.S. history.

The program included paid informants called “mosque crawlers” who the intelligence unit ordered to “bait” Muslims into making inflammatory statements on jihadism.

In 2012 the AP won a Pulitzer Prize for an investigative series on the Department’s secret intelligence unit that had infiltrated the al-Farooq mosque among others in the Tri-State area.

Davin Cohen, the Deputy Police Commission who ran the unit had been a former CIA official, raising questions about whether the Agency was conducting illegal surveillance on the U.S. homeland by using the NYPD as a surrogate.

On April 15th of 2014 the A.P. reported that the unit had been disbanded after coming under fire by community activists who accused the department of abusing civil rights.”

The Guardian later reported that in its six years of operation the so-called “demographics unit” didn’t produce a single actionable terrorism lead.

But in the ongoing struggle between protecting civil liberties and uncovering viable threats to the U.S. homeland, crucial leads were missed, particularly by the FBI.

In The Afterword to my latest HarperCollins book “Deal With The Devil,” I document why and how it took the Bureau so long to identify and interdict the al Qaeda cell that began metastasizing at the al-Farooq a quarter of a century ago when George Herbert Walker Bush was President.

TERRORIST LEADER KILLED IN PAKISTAN HAD BROWARD BACKGROUND

By Alfonso Chardy and Jay Weaver. MIAMI HERALD December 8th, 2014. A former Broward County college student who slipped out of South Florida just before the 9/11 terrorist attacks and later rose to the top ranks of al-Qaida was killed by Pakistani soldiers on Saturday.

Adnan El Shukrijumah was killed along with two other militants during a Pakistani Army assault in a mountainous tribal area bordering Afghanistan, the military said in a statement.

Shukrijumah’s death marks the end of a hunt for an elusive figure who came under the scrutiny of the FBI after al-Qaida’s attacks on U.S. soil. He was initially suspected of associating with some of the 9/11 hijackers while attending his late father’s mosque in Miramar as well as Broward Community College.

The FBI believes Shukrijumah left his family’s Miramar home weeks before the 9/11 attack, ostensibly traveling to Trinidad on business to buy sunglasses and children’s clothes for resale in South Florida flea markets.

Over the next decade, Shukrijumah would grow into a globe-trotting fugitive sought by the FBI as a leading operative for al-Qaida.

As al-Qaida’s head of external operations, the 39-year-old Shukrijumah occupied a position once held by Sept. 11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. The FBI listed the Saudi-born Shukrijumah as a “most wanted” terrorist and the U.S. State Department had offered up to a $5 million reward for his capture.

Shukrijumah was also under indictment on charges of directing an alleged suicide-bomb plot in 2009 against the New York City subway system.

For all Shukrijumah’s reported plotting and globe-trotting, his mother, Zuhrah, maintained that her son was falsely accused of being a terrorist. Asked in July 2011 at her Miramar home whether she had heard from him, she told the Miami Herald: “I don’t know if he is alive.”

But at some point in the late 1990s, the FBI says Shukrijumah became convinced that he must participate in “jihad,” or holy war, to fight perceived persecution against Muslims in places like Chechnya and Bosnia. He eventually went to a training camp in Afghanistan where he studied the use of weapons, explosives and battle tactics.

U.S. officials warned that Shukrijumah was especially dangerous to the nation because of the time he spent in America. The mystery surrounding his whereabouts — and whether he played a direct role in 9/11 — remained among the key unanswered questions.

“They are us. They know us intimately,” said Michael Scheuer, a former top analyst in the CIA unit created after 9/11 to track down al-Qaida founder Osama bin Laden, whom U.S. forces killed May 2, 2011, in a raid on his Pakistan hideout.

Shukrijumah became a leading member and perhaps the head of al-Qaida’s foreign operations subcommittee, a post that makes decisions on plans and recruitments, Rohan Gunaratna, a terrorism expert and author of the book Inside Al-Qaida: Global Network of Terror, told The Herald in 2011.

“He has moved up in the ranks because he’s very clever and because he knows the main target, the United States,” Gunaratna said.

Shukrijumah was born on Aug. 4, 1975, in Saudi Arabia. As the son of two foreigners, he wasn’t eligible for Saudi citizenship but obtained the citizenship of Guyana, on the northern shoulder of South America, through his father. Three siblings also were born in Saudi Arabia.

Shukrijumah spoke better English than Arabic, apparently because of time he spent in Trinidad, said Sofian Abdelaziz Zakkout, a Miami social worker who met him briefly in 2000 as the head of the American Muslim Association of North America.

He was 20 when the family came to Miramar, and he registered at what was then Broward Community College. School officials said he enrolled under the name Jumah A. El-Chukri “from summer 1996 to summer 1998, majoring in chemistry, but not graduating.”

His mother, Zuhrah, said he initially was interested in chemistry but switched to computers because it was an easier subject.

“He didn’t have enough knowledge,” she said. “He would study for one semester and start and stop.”

In between, she added, he traveled to buy flea market items, worked odd jobs in grocery stores and shops, sold used cars and phone cards, and assembled cell phones.

At one point, she said, her son returned to Saudi Arabia for the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca required of Muslims at least once in their lives if they can afford it.

Sept. 11 mastermind Khalid Sheik Mohammed first identified Shukrijumah as an al-Qaida operative while under U.S. interrogation after Mohammed’s capture in Pakistan in 2003, according to widely published reports.

Many contradictory reports have emerged about Shukrijumah.

He was sometimes described as a nuclear technician and commercial airplane pilot. Most of his aliases were variations of the word “Thayer,” Arabic for pilot. But there’s no public evidence that he ever took lessons in flying or nuclear technology.

One U.S. military intelligence analyst assigned to a unit in Afghanistan that tracked “high value” al-Qaida targets in 2006-07 said that while Shukrijumah’s name came up in some reports, he “was not on our top 10 list.”

Yet he was connected to so many alleged plots, and reportedly spotted in so many countries — Panama, Honduras, Mexico, Trinidad, Canada, Britain, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Yemen — that he was called the Elvis Presley of al-Qaida.

While much was known about Shukrijumah, gaps remained. The most crucial: whether he was in contact with the 9/11 hijackers and pilots. Sixteen of the 19 hijackers lived in or visited South Florida before the attacks.

One U.S. immigration inspector told investigators she was “75 percent sure” she saw Shukrijumah with Mohamed Atta, one of the 9/11 pilots, and another man at the former Immigration and Naturalization Service building on 79th Street in Miami on May 2, 2001.

According to a 2004 report by the national panel that investigated the 9/11 attacks, Atta sought to extend the visa of one of his two companions, probably Ziad Jarrah, the pilot of United Airlines Flight 93, which crashed in a Pennsylvania field.

The 9/11 Commission report noted that “to date” no information had surfaced associating Shukrijumah with the plot, but it didn’t rule it out, given that he “is considered a well connected al-Qaida operative.”

One of those connections, according to the report, was his father, an imam who testified on behalf of Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, the Egyptian who is serving a life sentence in a U.S. prison for a plot to bomb the United Nations headquarters in New York, along with the Lincoln and Holland tunnels and the George Washington Bridge.

U.S. authorities discovered that plot as a result of investigations into the first attack on the World Trade Center, in 1993. A key plotter in that attack was Ramzi Yousef, a nephew of Khalid Sheik Mohammed.

Shukrijumah’s father, Gulshair, served as an imam, or prayer leader, at al Farooq mosque in Brooklyn, where Rahman once preached. He moved the family to Miramar in 1995, when he became imam of al Hijra Mosque, which then was next door to the family home.

In March 2001, FBI agents deployed an informant to infiltrate the mosque run by Shukrijumah’s father because they were targeting another Broward Community College who attended, Imran Mandhai.

The informant recorded Mandhai vowing to establish a jihad cell that would target electrical substations, Jewish institutions and a National Guard armory. Mandhai tried to recruit Shukrijumah, but he resisted and declined to join, according to the recordings.

The feds kept their focus on Mandhai and his co-conspirator, Shueyb Mossa Jokhan. After 9/11, the FBI and federal prosecutors ramped up their investigation and eventually indicted the pair in spring 2002. Mandhai was convicted of conspiracy to destroy electrical stations and other targets; Jokhan testified against him.

Former U.S. Attorney Jeffrey Sloman, who prosecuted the case along with current Miami-Dade Circuit Judge John Schlesinger, said it was the country’s first successful terrorism-related prosecution after 9/11.

Sloman said he thought it was more than sheer coincidence that Shukrijumah was in Broward at the time the likes of Mohamed Atta and other terrorists were in South Florida.

“It’s pretty scary,” he said. “Not even Carl Hiaasen could make this stuff up.”

Information from the Associated Press was used to supplement this story.

Read more here: http://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/broward/article4368512.html#storylink=cpy

Recent Comments