TRIPLE CROSS: Chapter One – The Deep Black Hole

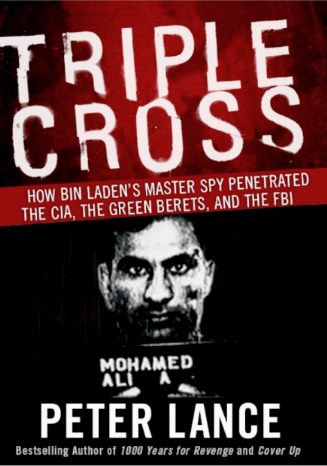

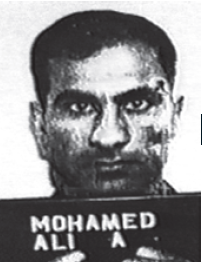

By Peter Lance (c) 2007 + 2009 On October 20, 2000, after tricking the U.S. intelligence establishment for years, Ali Mohamed stood in handcuffs, leg irons, and a blue prison jumpsuit before Judge Leonard B. Sand in a Federal District courtroom in Lower Manhattan. Over the next thirty minutes he pleaded guilty five times, admitting to his involvement in plots to kill U.S. soldiers in Somalia and Saudi Arabia, U.S. ambassadors in Africa, and American civilians “anywhere in the world.” The goal of the al Qaeda terrorists he trained, he said, was to “kidnap, murder and maim.” His career in espionage had earned him a death sentence in an Egyptian trial the year before. But now, before the federal judge, Ali was seeking mercy.

By Peter Lance (c) 2007 + 2009 On October 20, 2000, after tricking the U.S. intelligence establishment for years, Ali Mohamed stood in handcuffs, leg irons, and a blue prison jumpsuit before Judge Leonard B. Sand in a Federal District courtroom in Lower Manhattan. Over the next thirty minutes he pleaded guilty five times, admitting to his involvement in plots to kill U.S. soldiers in Somalia and Saudi Arabia, U.S. ambassadors in Africa, and American civilians “anywhere in the world.” The goal of the al Qaeda terrorists he trained, he said, was to “kidnap, murder and maim.” His career in espionage had earned him a death sentence in an Egyptian trial the year before. But now, before the federal judge, Ali was seeking mercy.

In short but deliberate sentences, Mohamed peeled back the top layer of the secret life he’d led since 1981, when radical members of his Egyptian army unit gunned down Nobel Prize winner Anwar Sadat. A highly educated master spy, fluent in four languages, Mohamed told of how he had risen from a young recruit in the virulently anti-American Egyptian Islamic Jihad to become Osama bin Laden’s most trusted security advisor. He described how al Qaeda cell members from Kenya had infiltrated Mogadishu, Somalia, in the 1993 campaign that ultimately downed two U.S. Black Hawk helicopters; how he had brokered a terror summit between al Qaeda and the hyper-violent Iranian Party of God known as Hezbollah; and how he had trained al Qaeda jihadis in Afghanistan and Sudan, teaching them improvised bomb building and schooling them in the creation of secret cells so that they could operate in the shadows.

On this last bit of tradecraft, he’d literally written the book. If there was ever a shadow man in the dark reaches of al Qaeda, it was the triple spy born Ali Abdel Saoud Mohamed. Because there is so little on the public record about him and because his career resulted in so much terror and death, we will produce his words from that plea session throughout this book, verbatim.

Perhaps his most telling admission came when Judge Sand asked his objectives. Mohamed answered by restating al Qaeda’s longstanding goal of driving the U.S. out of the Middle East; particularly Saudi Arabia, where troops had been stationed since August 7, 1990. What would make Mohamed’s leader, Osama bin Laden, think he could achieve that goal? At that point, without naming him, Mohamed cited the example of how President Ronald Reagan had withdrawn U.S. troops from Lebanon following the deadly Marine barracks bombing in 1983—an act of terror that some suspect Ali himself may have had a hand in

THE COURT: The overall objective of all of these activities you described was, what?

MOHAMED: . . . just to attack any Western target in the Middle East; to force the government of the Western countries just to pull out . . . not interfere in the—

THE COURT: And to achieve that objective, did the conspiracy include killing nationals of the United States?

MOHAMED: Yes, sir. Based on the Marine explosion in Beirut in 1983 and the American pull-out from Beirut, they will be the same method, to force the United States to pull out from Saudi Arabia.

THE COURT: And it included conspiracy to murder persons who were involved in government agencies and embassies overseas?

MOHAMED: Yes, your honor.

THE COURT: And to destroy buildings and properties of the United States?

MOHAMED: Yes, your honor.

THE COURT: And to attack national-defense utilities?

MOHAMED: Yes, your honor.

But the most important aspect of that plea session was what was left unsaid. In that Southern District Courtroom nearly two years before the attacks of September 11, Ali Mohamed uttered nothing on the record about his most stunning achievements: how he had slipped past a State Department watch list and into America, seduced a Silicon Valley medical technician into marriage, joined the U.S. Army, and gotten himself posted to the highly secure base where the Green Berets and Delta Force train. He didn’t say a word about how he’d moved in and out of contract spy work for the CIA and fooled FBI agents for six years as he smuggled terrorists across U.S. borders, and guarded the tall Saudi billionaire who had personally declared war on America: Osama bin Laden.

“Those who know Ali Mohamed say he is regarded with fear and awe for his incredible self-confidence, his inability to be intimidated, [his] absolute ruthless determination to destroy the enemies of Islam and his zealous belief in the tenets of militant Islamic Fundamentalism.”

That’s how terrorism expert Steven Emerson described Mohamed after the FBI finally arrested him in 1998. Though the Bureau had been onto his terrorist connections since the 1989, it took the simultaneous attacks on the Embassies in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi to jolt them into the admission that the Justice Department had been conned; that whatever intelligence crumbs he’d thrown to the FBI, Mohamed had gotten back ten times more. Worse, he’d led a campaign of disinformation that lulled the Bureau into a vast underestimation of the al Qaeda threat.

Mohamed’s commanding officer at Fort Bragg, Lt. Col. Robert Anderson, was more specific: “Ali Mohamed is probably the most dangerous person that I ever met in my life.”

He wasn’t the devil himself, Anderson said, in an interview for this book. He was more like “The aide to the devil. He was a fanatic. He had an air about him; a stare, a very coldness that was pathological.” But Anderson noted that Ali “would shift into a very nice polite individual when it was to his advantage.”

Now, in the courtroom, as he stood cuffed and stooped over, feigning humility, Ali Mohamed played yet another role—that of the contrite and broken jihadi, a man willing to cooperate with the Feds. Finally, once and for all, the hope was that he would give up his secrets. But in the poker game between “asset” and FBI control agent, Mohamed held most of the face cards. He had stung the Bureau repeatedly over the years and he knew that in the end, they would want to hide the truth.

“Ali knew where the bodies were buried,” said one former FBI agent. “In fact, he dug most of the graves himself. There was just no way that [FBI] management wanted that story to come out.”

“With his connections to U.S. law enforcement and intelligence,” says Emerson, “I’ve never seen a terrorist with such a storied background.” As the man who had sat in a room with the “terror prince,” while bin Laden personally targeted the Nairobi embassy back in 1994, Mohamed should have been the star witness in the embassy bombing trial, which was just months away. Yet Patrick Fitzgerald, the lead prosecutor, never called him.

Why did the Feds let Ali Mohamed sit out that trial? Why did they make a secret plea arrangement with him and yet not force him to testify? Because Mohamed wasn’t just the government’s best witness to al Qaeda’s successes, he was also the best witness to the failures of the FBI and the CIA to stop bin Laden’s terror campaign.

It was a string of attacks that stretched from the murder of Rabbi Meier Kahane in 1990 through the bombing of the World Trade Center in 1993, up through the assault on the U.S.S. Cole in 2000, and on to the second attack on the Twin Towers in 2001. Mohamed had been an FBI snitch for much of that decade and he’d been on the Bureau’s radar since 1989. What he knew about the FBI’s missteps could fill a metaphorical book, and the U.S. Justice Department was determined that it would never be published.

And yet even today, years after pleading guilty to crimes that would have ended any other terrorist’s life via lethal injection, Ali Mohamed remains a legal black hole. Minutes after that hearing he was locked away, hidden from public scrutiny; It’s been nearly six years and one of the discoveries made in this investigation is that Judge Sands has yet to pronounce sentence.[x] Today Mohamed exists in a kind of legal no-man’s-land, a prisoner of the Feds whose name appears nowhere on the Bureau of Prisons inmates roster. His case file in the Southern District is heavily redacted or otherwise sealed. Only a handful of people in the Justice Department know the full details of his plea arrangement.

His wife, Linda Sanchez, remains loyal to him and hopeful that some day the Feds will set him free. “He’s done a lot for the government,” she said in an exclusive interview for this book. “Someday you’ll know it all, but I can’t discuss it.”

Mohamed’s lawyers, James Roth and Lloyd Epstein, have steadfastly resisted any attempts by journalists to get the full story. But from interviews with those who knew him in North Carolina and Silicon Valley, the depth of Mohamed’s deception is becoming more clear. “It boggles the mind that anyone who lived this close here could possible have anything to do with something this horrible,” said an old acquaintance from California. “It makes you wonder about anyone else we were so taken in by.” Another U.S. official who crossed Mohamed’s path had a different opinion. “You could sit and have lunch with him and he’d be as nice as pie. But if the call came to blow you up, there is no question in my mind that Ali would blow you up.”

DEATH OF A PHARAOH

On October 6, 1981, Anwar Sadat, the Egyptian president who had won a Nobel Prize for making peace with Israel, sat in a reviewing stand near Cairo’s unknown soldier tomb. Surrounded by four layers of bodyguards during an annual troop review commemorating the Yom Kippur War, Sadat looked upward as an elite Egyptian Air Force squadron performed flybys overhead. Suddenly, one of the troop carriers passing the reviewing stand came to an abrupt stop. Five men jumped off, led by a radical Army lieutenant named Khalid al-Islambouli. They rushed the reviewing stand, throwing grenades and firing bursts from automatic weapons. Thirty-five seconds later, a bullet ripped through an artery in Sadat’s chest. “ Impossible,” he exclaimed, “impossible.” Then he fell dead.

On October 6, 1981, Anwar Sadat, the Egyptian president who had won a Nobel Prize for making peace with Israel, sat in a reviewing stand near Cairo’s unknown soldier tomb. Surrounded by four layers of bodyguards during an annual troop review commemorating the Yom Kippur War, Sadat looked upward as an elite Egyptian Air Force squadron performed flybys overhead. Suddenly, one of the troop carriers passing the reviewing stand came to an abrupt stop. Five men jumped off, led by a radical Army lieutenant named Khalid al-Islambouli. They rushed the reviewing stand, throwing grenades and firing bursts from automatic weapons. Thirty-five seconds later, a bullet ripped through an artery in Sadat’s chest. “ Impossible,” he exclaimed, “impossible.” Then he fell dead.

On the day of the assassination one of the shooters was gunned down immediately. A second escaped, but was captured shortly thereafter; three of the others were wounded. Still, the ringleader, al-Islambouli, was ecstatic. “I have slain Pharaoh,” he cried, “and I do not fear death.”

The murder of Sadat was a seminal event in what would become a decades-long jihad, or holy war, against the West. The assassination came a year after Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, the assassins’ spiritual leader, issued a fatwa, a religious order, condemning Sadat. Rahmanwas arrested, but later acquitted in the assassination plot. He would go on to make an indelible mark on the future of radical Islam.

THE BLIND SHEIKH

Blinded shortly after birth, Omar Abdel Rahman had memorized the Koran by the age of eleven. He earned a degree in Koranic studies in 1972 from the Al Azhar University in Cairo, where he was influenced by the writings Sayyid Qutb, an intellectual who was an early adherent of the Muslim Brotherhood.

The Brotherhood, or Ikhwan, was founded in 1928. It spawned two of Egypt’s most virulent terror sects: The al Gamma’a Islamayah (Islamic Group), run by Rahman, and the Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ), led by Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri, the scion of a prominent Cairo family. Begun as a student movement within the Brotherhood, the EIJ splintered off in the early 1970s to become a covert military arm, while the Ikhwan sought more mainstream political legitimacy. Since al-Islambouli, the lead Sadat shooter, was an outspoken EIJ member, al-Zawahiri was jailed as a co-conspirator. One of three hundred arrested, the bespectacled surgeon stood trial as “Defendant No. 113.” He was convicted on weapons charges and sentenced to three years in an Egyptian prison, where he later claimed that he was severely tortured.

But incarceration only served to radicalize the young doctor. He emerged in 1984 as a leading spokesman for jailed Islamic militants. One of his fellow inmates was Mustafa Shalabi, a thirty-year-old red-headed electrical contractor who, years later,would establish an early beachhead for the jihad at a mosque in Brooklyn.

In the decade to come, Rahman, al-Zawahiri, and Shalabi would collaborate with Osama bin Laden, weaving the threads of the IG and the EIJ into the radical new terror network called al Qaeda. Each of the three Egyptian leaders would have a significant impact on the life of Ali Mohamed, offering him direct access to bin Laden, the terror prince, himself.

LIGHTING ALI’S FUSE

Born in Kafr El Sheikh, Lower Egypt in 1952, Mohamed seems to have been launched on his trajectory after an incident that occurred in 1966, when he was fourteen. According to Jack Cloonan, the FBI agent who debriefed him after 9/11, “That’s when his fuse was lit.”

“He was up there in the Sinai,” says Cloonan, “with a very trusted uncle of his [who] was a goat herder, and the goats wandered over the border and somehow got into Israel. The Israeli army troops who were up there guarding that part of Sinai thought that these guys were driving these goats and crossing the border to cover up the tracks of infiltrators. So they came to Ali’s uncle and roughed him up. They killed some of his livestock, and then they took his uncle’s sandals off and took hot water that they were boiling for tea, and poured it over his feet.”

From that moment as a teenager, says Cloonan, Ali Mohamed decided “he was going to get revenge.” Years later, after he’d infiltrated Silicon Valley, Ali would recruit a young Egyptian medical student with a similar revenge story involving an accidental border crossing. Khalid Dahab was the son of an airline pilot and a female medical doctor from a wealthy family in Alexandria. As a schoolboy in 1973, Dahab became radicalized after his father’s Cairo-bound flight was reportedly shot down by Israeli fighter jets. As Cloonan observes, such revenge motivations are “a paramount driving force” for much of modern radical Islam. As another source with the State Department’s Diplomatic Security service puts it: “A man on the West Bank is killed by Israeli tanks. His daughter grows up and just lives to avenge that death. One night she straps on a suicide vest and blows up a café full of innocent people celebrating a wedding in Tel Aviv. The next day a village gets leveled in Gaza in retaliation. It’s a circle of hate.”

For Ali Mohamed, the circle was more like a straight line. After attending Cairo Military Academy, he earned two bachelors degrees and a masters in psychology from the University of Alexandria; then, in 1971, he joined the Egyptian Army. Over the next thirteen years he became an intelligence officer, rising to the rank of major in an Egyptian special forces unit. Fluent in Egyptian and Arabic from an early age, Ali soon mastered English and Hebrew as well. He was frequently assigned to protect Egyptian diplomats overseas, where his experience broadened.But he longed to play a more active role in special operations. “This guy loves action. Loves the intrigue,” says Cloonan. So Mohamed volunteered for a series of dangerous clandestine missions, participating in operations in Libya and elsewhere. “He landed with helicopters to take over a jail and shoot it out with the Libyans,” Cloonan says. It was only one of many special ops he would do in the years that followed.

THE PERFECT ALIBI

By 1981, Ali Mohamed had joined al-Zawahiri’s Egyptian Islamic Jihad. In fact, the man who later became his commanding officer in the U.S. Army, says that Ali once confessed to being in the very same unit that shot Sadat. But if he was ever a suspect in that slaying, he had the perfect alibi: At the time of the assassination, Mohamed was assigned to a U.S.-Egyptian officer exchange program at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Training alongside the Fifth Special Forces, Mohamed was tutored by Green Beret officers in reconnaissance, unconventional warfare, and counterinsurgency tactics. As Joseph Neff and John Sullivan reported in the Raleigh News & Observer, he graduated from the program after four months, collecting a diploma with a Green Beret on it. He also participated in Operation Bright Star, a semi-annual U.S./Egyptian joint military exercise.

Yet, as a devoted Muslim who prayed five times a day—and wasn’t afraid to express his political views—Mohamed was under increasing pressure in the Egyptian Army.

“Being Special Forces made him of real interest to certain cells within the Brotherhood,” says Cloonan. “But his religious fervor also made Ali a target in the Egyptian army.” Mohamed’s association with the Egyptian Islamic Jihad raised suspicions. According to Nabil Sharef, a former intelligence officer, now a university professor, Mohamed was considered too religious, and potentially radical.

By 1984, as Egypt’s new president, Hosni Mubarak, sought to thin the Egyptian army’s ranks of Islamic zealots, Ali’s brand of religious fervor forced his discharge.

“He got mustered out,” says Cloonan, “and he was bitter.” But soon, after leaving uniform, Ali attracted the attention of Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri, who assigned him a series of missions to test his capabilities and prove his bona fides.

“One of the first things they ask him to do,” Cloonan says, “is surveillance on airplanes, because they want to hijack a plane. So Ali goes out—because he’s got some of the best training going—and does surveillances on aircraft in Cairo. How you bridge the fence, how to get on board, how you’re going to do it from A to Zed. That’s pretty scary, because guess what happens down the road when you talk about airplanes and hijacking?”

Ali soon swore a bayat, an Islamic oath of allegiance, to al-Zawahiri and the EIJ. “You’re my sheik. You’re my Emir,” says Cloonan, quoting Mohamed’s pledge to the doctor. “I pledge my bayat to you.” Working for the doctor as a de facto spy, Mohamed proved himself further by getting hired by Egyptair, the Egyptian state airline His job description was, security advisor.

“It gives him access” says Cloonan. “And no one’s going to raise a question.”

During his eighteen-month tenure at Egyptair, Mohamed was able to study the latest air piracy countermeasures. As the disciple of a radical Islamic leader like al-Zawahiri, Mohamed was undergoing his first real test as a double agent, and he passed with flying colors. His next assignment from the doctor was more of a challenge. “Zawahiri says, Infiltrate the United States government,” says Cloonan, “An intelligence service.”

So Ali Mohamed set his sights on the Cairo station of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Recent Comments