Operation Able Danger

Sept. 11th, 2010. The New York Times, the A.P. and Fox News break the story of how Tony Shaffer’s Afghan war memoir: “Operation Dark Heart” is being censored by the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) after it had already passed a vetting by U.S. Army reviewers. Fox News national security correspondent Catherine Herridge reported that DIA “Attempted to block key portions of the book that claim “Able Danger” successfully ID’d hijacker Mohammed Atta as a threat to the U.S. before the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks.”

Sept. 11th, 2010. The New York Times, the A.P. and Fox News break the story of how Tony Shaffer’s Afghan war memoir: “Operation Dark Heart” is being censored by the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) after it had already passed a vetting by U.S. Army reviewers. Fox News national security correspondent Catherine Herridge reported that DIA “Attempted to block key portions of the book that claim “Able Danger” successfully ID’d hijacker Mohammed Atta as a threat to the U.S. before the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks.”

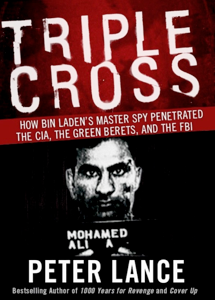

What follows is the most complete telling of the Able Danger story in print form: chapters from Peter Lance’s 2006 book (updated in 2009) TRIPLE CROSS: How bin Laden’s Master Spy Penetrated the CIA, the Green Berets and the FBI. For the first time, the book presents an explanation for why the Pentagon ordered destroyed 2.5 terabytes of al Qaeda related intelligence gathered by the Able Danger data miners.

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE OPERATION ABLE DANGER

If Ali Mohamed was Osama bin Laden’s operational spy, a man who combined the double threats of intelligence officer and on-the-ground commando, one of the soldiers who embodied that same skill set for America was a Bronze Star winner named Anthony Shaffer.

Commissioned as an officer in the Ohio National Guard in 1983, Shaffer was selected early in his career to train at “the Farm,” the CIA’s legendary school for clandestine operatives at Camp Perry, Virginia. Over twenty-four years in the military, Tony Shaffer worked a series of active duty secret ops and task force assignments, alternating between roles as an intelligence officer with the Pentagon’s J2 Directorate and as a clandestine operative with the J3. In September 1999, now a major, Tony Shaffer was running a top secret operation called Stratus Ivy, supporting various DOD “black” operations, when he was assigned to brief four-star general Pete Schoomaker, then head of SOCOM.

“With my unit’s permission,” says Shaffer, “I was able to brief General Schoomaker at a level that was beyond Top Secret. After the briefing he said to me, ‘I need you for a special project.’ He looked over at the STO Chief, the head of Special Technical Operations, and said, ‘I want Shaffer read into the project ASAP.’ The next day I was read into Able Danger.’” In the months that followed, Tony would serve as a liaison between the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), the Army and SOCOM.

“Able Danger had a duel purpose,” says Shaffer. “[After the] African embassy bombings, it was clear to the Pentagon that al Qaeda was our new enemy, and that eventually we would have boots on the ground against them. So the idea was to identify their members and to take them out. The operation wasn’t called Able Fun or Able Picnic. It was Able Danger, because the sense within the military community was that we needed to get these guys before they could get us again.” Over the decades, among the thousands of code names chosen by the Pentagon to describe secret and open source military operations, the prefix “Able” had traditionally been used in conjunction with NATO and nuclear weapons-related exercises. The fact that it was now being affixed to a secret operation relating to terrorism, suggests how seriously the army and the DIA took the al Qaeda threat.

Shaffer says that Able Danger was “the military version of Alec Station,” the CIA’s unit tasked with collecting al Qaeda-related intelligence. The operation’s data-mining center was located at the Land Information Warfare Activity (LIWA) at Fort Belvoir, Virginia. Known as “spook central,” Fort Belvoir housed the Information Dominance Center—a building full of army intelligence “geeks,” whose bullpen area was designed to look like the bridge of the Starship Enterprise from Star Trek.

The lead LIWA analyst running the data mine was Dr. Eileen Priesser, a double Ph.D. The operations officer was a decorated U.S. Navy captain named Scott Phillpott. Army Major Eric Kleinsmith was LIWA’s intelligence chief. J.D. Smith and Jacob L. Boesen, working as a contract analysts from Orion Scientific, designed many of the link charts in which the “deep data points” connecting the key al Qaeda players were represented graphically.

“You would ask them, for example, to look at Khalid Shaikh Mohammed,” says Shaffer, “and these search engines would scour the internet 24/7 looking at any number of open-source databases, from credit reporting agencies to court records and news stories to Lloyd’s of London insurance records. You name it. Once a known associate of KSM was found, they would go through the same process for that individual.” One IDC analyst I spoke to described it as “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon on steroids.”

The lead LIWA analyst running the data mine was Dr. Eileen Priesser, a double Ph.D. The operations officer was a decorated U.S. Navy captain named Scott Phillpott. Army Major Eric Kleinsmith was LIWA’s intelligence chief. J.D. Smith and Jacob L. Boesen, working as a contract analysts from Orion Scientific, designed many of the link charts in which the “deep data points” connecting the key al Qaeda players were represented graphically.

“You would ask them, for example, to look at Khalid Shaikh Mohammed,” says Shaffer, “and these search engines would scour the internet 24/7 looking at any number of open-source databases, from credit reporting agencies to court records and news stories to Lloyd’s of London insurance records. You name it. Once a known associate of KSM was found, they would go through the same process for that individual.” One IDC analyst I spoke to described it as “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon on steroids.”

Told to “Start with the words ‘Al Qaeda’ and go,” the LIWA data crunchers began an initial harvest in December 1999. The data grew fast and exponentially, and before long it amounted to two terabytes—equal to about 9 percent of the books in the Library of Congress. “It was a mile wide and an inch deep,” says Kleinsmith. “Naturally only a small percentage of the data related to terrorism,” says Tony, “So we would have to neck it down —cull it — until we had some substantive hits.” Within months, Operation Able Danger had uncovered some astonishing intelligence.

DISCOVERING THE HIJACKERS

“We found active an al Qaeda cell in the U.S linked to radical Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman,” says Shaffer, now a lieutenant colonel. “That was most frightening—that as late as early 2000 we detected that kind of al Qaeda presence here.”

Examining Sheikh Rahman’s Brooklyn cell—which operated out of Ali Mohamed’s old stomping grounds, the al Farooq mosque—the LIWA analysts made another alarming discovery. “We identified lead 9/11 hijacker Mohammed Atta, Marwan al-Shehhi, who flew UA 175 into the South Tower of the Trade Center, and two of the muscle hijackers aboard AA 77, which hit the Pentagon,” says Shaffer. That linkage was made months before any of the other Big Five intelligence agencies would trip to their presence.

Coming as it did in early 2000, the identification of Khalid al-Midhar and Nawaf al-Hazmi was a crucial find for the SOCOM operation.

Of all the 9/11 hijackers, these two Saudis had the longest records of al Qaeda involvement, and beginning in January 2000, they soon became the most visible of the 19 operatives. In fact, the two failed pilots appeared on the radar of the NSA, the CIA, and the FBI so many times in the eighteen months before 9/11 that the U.S. intelligence community had multiple opportunities to thwart the plot.

Al-Midhar and Al-Hazmi were the poster boys who came to symbolize the “stovepiping” between U.S. agencies in their failure to share intelligence before 9/11.

Until now, most of the blame for failure to track the two Saudis has been leveled at the Central Intelligence Agency. As recently as August 2006, in his 9/11 book The Looming Tower, New Yorker writer Lawrence Wright charged that the CIA’s hoarding of intelligence on al Midhar, al Hazmi, and another key al Qaeda operative “may, in effect, have allowed the September 11 plot to proceed.”

Until now, most of the blame for failure to track the two Saudis has been leveled at the Central Intelligence Agency. As recently as August 2006, in his 9/11 book The Looming Tower, New Yorker writer Lawrence Wright charged that the CIA’s hoarding of intelligence on al Midhar, al Hazmi, and another key al Qaeda operative “may, in effect, have allowed the September 11 plot to proceed.”

But even if the FBI had received no help from any other agency, we’ve uncovered compelling evidence that the agents of Squad I-49 (the bin Laden Squad in the FBI’s New York Office) should have tripped to the presence of the two hijackers in the U.S. months before they flew AA Flight 77 into the Pentagon.

After his capture following the Embassy bombings in 1998, Mohamed Rashed Daoud al-’Owali, the Saudi who drove the truck, gave FBI agents the number of a safe house in Sana’a Yemen maintained by Sameer Mohammed Ahmed al-Hada, the brother-in-law of Khalid al-Midhar.

“We got the number from a confession from Al-’Owhali ,” says former FBI agent and Squad I-49 operative Jack Cloonan. “We gave the information to the [CIA] Chief Station in Nairobi.”

The house was being used as an al Qaeda “logistics center” or “switchboard” in much the same way Khalid Dahab (Ali Mohamed’s protegé) had used his one-room apartment in Santa Clara, California—to patch through phone calls from bin Laden operatives worldwide. In fact, it was later revealed that the Saudi billionaire himself called the Yemen house multiple times between 1996 and 1998.

As a result, the NSA and the CIA planted bugs inside the house, installed phone taps, and even went so far as to monitor visitors coming in and out of the dwelling using spy satellites.

“The NSA and the Agency were monitoring it for two years,” says Cloonan.

It was the phone line in that Yemeni safe house that led the CIA to the discovery of the single most important al Qaeda planning session prior to the 9/11 attacks. It was scheduled for January 5th-8th 2000 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, the Southeast Asian capital known to intelligence analysts as “K.L.”

THE 9/11 SUMMIT

As early as 1998, the NSA had picked up references to al-Midhar, Nawaf al-Hazmi and his brother Salem, who would also become a suicide hijacker on 9/11. In fact, in his book Military Intelligence Blunders, Col. John Hughes-Wilson reports that, “Al Hazmi was well known to the NSA in Fort Meade, Maryland. Their signals intelligence operators had intercepted a message in 1999 proving that al Hazmi was an al Qaeda terrorist and that he was plotting to hijack American airliners.”

When al-Midhar left the Yemeni safe house in early 2000, agents from eight CIA offices and six allied intelligence services were reportedly asked to track him. Officials in the United Arab Emirates even made copies of al-Midhar’s passport when he traveled through Dubai, so that by the time he reached Kuala Lumpur, the CIA knew his full name and the fact that he was carrying a U.S. multiple entry visa.

By January 4th, a CIA operative made an extraordinary mistake that ignited one of the great interagency disputes on the road to 9/11. After receiving a copy of al-Midhar’s picture, the Agency failed to add him to the Watch List. Worse yet, deliberate steps were taken to prevent the FBI from getting the information. As the 9/11 Commission’s final report told the story: “An FBI agent detailed to the Bin Ladin unit at CIA attempted to share this information with colleagues at FBI headquarters. A CIA desk officer instructed him not to send the cable with this information. Several hours later, this same desk officer drafted a cable distributed solely within CIA alleging that the visa documents had been shared with the FBI. She admitted she did not personally share the information and cannot identify who told her they had been shared. We were unable to locate anyone who claimed to have shared the information. Contemporaneous documents contradict the claim that they were shared.”

Later, the FBI would claim that their agents weren’t informed of al-Midhar’s al Qaeda ties until he was back in the U.S. and within weeks of boarding AA Flight 77. But back in January 2000, while the Malaysian meeting was still in progress, a CIA officer assigned to the FBI’s Strategic Information Operations Center (SIOC) at the Bureau’s Washington headquarters reportedly briefed two separate FBI agents on al-Midhar’s activities.

As terrorism analyst Paul Thompson reports in his detailed review of the al-Midhar incident for historycommons.org: “This agent then sends an e-mail to another CIA agent describing ‘exactly’ what he told the two FBI agents. One section reads, ‘This continues to be an [intelligence] operation. Thus far, a lot of suspicious activity has been observed, but nothing that would indicate evidence of an impending attack or criminal enterprise. [The first FBI agent was] told that as soon as something concrete is developed leading us to the criminal arena or to known FBI cases, we will immediately bring FBI into the loop. Like [the first FBI agent] yesterday, [the second FBI agent] stated that this was a fine approach, and thanked me for keeping him in the loop.’ The two FBI agents are not told about al-Midhar’s US visa.”

The fact that a key CIA representative at the FBI felt that nothing observed at the Malaysian summit suggested “evidence of an impending attack” is stunning when one considers who was in attendance at the three-day session, which took place at a condominium overlooking a Jack Nicklaus-designed golf course. The condo was owned by Yazid Sufaat, a Malaysian who traveled to Afghanistan in the summer of 2000 and later acknowledged his al Qaeda ties.

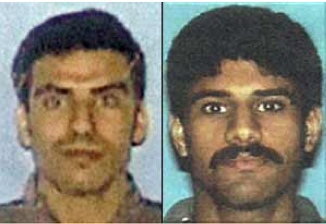

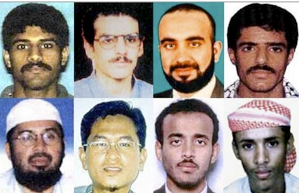

Participants in the January 2000 Malaysian meeting, in person or by phone.Top (left to right) Nawaf Al-Hazmi, Khalid Al-Midhar, Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, Khallad bin Atash. Bottom (left to right) Riduan Isamuddin (aka Hambali) Yazid Sufaat, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Fahad al-Quso.

Participants in the January 2000 Malaysian meeting, in person or by phone.Top (left to right) Nawaf Al-Hazmi, Khalid Al-Midhar, Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, Khallad bin Atash. Bottom (left to right) Riduan Isamuddin (aka Hambali) Yazid Sufaat, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, Fahad al-Quso.

Details of the Malaysian terror summit have been a matter of public record for some time, but of the eight attendees initially reported, the one most disputed by scholars and reporters is Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, who by then, was in the late stages of perfecting his nephew Ramzi Yousef’s planes operation.

A number of mainstream media accounts, from CNN to the Los Angeles Times, initially put KSM at the summit. Singapore-based terror expert Ronan Gunarata later testified before the 9/11 Commission that he had seen interrogation reports in which KSM admitted running the summit, and in a 2003 study of radical Islam in Southeast Asia,Dr. Zachary Abuza, a U.S. terrorism scholar, reported that KSM was at the conference.

But Khalid Shaikh’s attendance in Kuala Lumpur was later denied by U.S. officials, and some researchers like Dr. Abuza are now backtracking on whether he was physically in at the K.L. condo. As Michael Isikoff and Mark Hosenball reported in Newsweek, KSM’s presence at the meeting “would make the intelligence failure of the CIA even greater. It would mean the agency literally watched as the 9/11 scheme was hatched—and had photographs of the attack’s mastermind . . . doing the plotting.”

In any case, KSM’s number-two in the planes-as-missiles plot, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, was there, along with Khallad bin Atash, a senior al Qaeda operative who played a key role in executing the African Embassy bombings. Atash, who lost a leg reportedly fighting in Afghanistan and now wore a metal prosthesis, would go on to mastermind the attack on the U.S.S. Cole later in 2000. One of his operatives from the Cole plot, Fahad al-Quso, was also present at the K.L. summit, along with Riduan Ismuddin, a.k.a. Hambali, the head of Jemaah Islamiya, the Indonesian wing of al Qaeda. It was Hambali who served with his wife on the board of Konsonjaya, the Malaysian front company that funded the Yousef-KSM Manila cell where the 9/11 plot was born.

To use a metaphor Patrick Fitzgerald would understand from his mob-busting days, the K.L. summit was the equivalent of the infamous Mafia summit in 1957 at Apalachin, New York, which finally alerted the FBI to the presence of the national organized crime syndicate J. Edgar Hoover later identified as “La Cosa Nostra.”

“Arguably it was like the Commission meeting,” ex-FBI agent Jack Cloonan concurs.

The Malaysian summit was so high-profile that, according to intelligence scholar James Bamford, it was monitored, as it took place, at the highest levels of the intelligence community– even at the White House. “Updates were circulated to senior officials on January 3 and 5,” wrote Bamford in his compelling study A Pretext for War. Included on the list, per Bamford, was Alec Station at CIA, where Squad I-49 had a representative. White House national security advisor Sandy Berger was reportedly kept up to speed on the conference and according to Bamford FBI director Louis Freeh himself was briefed on January 6th

At the request of the CIA, the three-day meeting at Sufaat’s condo was even photographed and videotaped by the Malaysian intelligence service, known as the Special Branch.

Attended by a who’s-who of top al Qaeda operational killers, that meeting set the stage for not only the Cole bombing and the 9/11 attacks, but also the October 2002 Bali bombings, to which Hambali was later linked. Even if KSM wasn’t there physically, the presence of his deputy bin al-Shibh, Hambali, and Khallad bin Atash should have set off flashing red lights throughout the U.S. intelligence community—especially at the CIA and the FBI, which was now investigating the African embassy bombings ex post facto.

LINKING THE K.L. SUMMIT TO THE AFRICAN BOMBINGS

We now know, from the testimony during the March 2006 penalty phase at the trial of accused “twentieth hijacker” Zacarias Moussaoui, that the one-legged Khallad was also an operational leader of the embassy bombing plot. After his capture, Mohamed Rashed Daoud al-’Owali admitted that before the August 1998 bombing he was instructed to go to Pakistan. There he met bin Atash, who told him to prepare for a “martyrdom mission” in which he would drive a truck full of explosives into a target.

“That information came to the FBI on or about Sept. 9, 1998,” says a source close to Moussaoui’s defense team. “Later al-’Owali gives up the Sana’a Yemen safe house of al-Midhar’s brother-in-law Ahmed al-Hada. That intelligence led to the NSA and CIA wiretaps. So you have to ask yourself, why wasn’t the FBI all over that K.L. meeting? Why wait for the CIA to give them photographs? Why didn’t they have their own wiretaps on the Sana’a safe house and track al-Midhar on their own? Clearly they had criminal jurisdiction to pursue the leads as a result of Khallad’s ties to the Embassy bombing.”

David Kaplan and Kevin Whitelaw reported in U.S. News & World Report that “The content of some of [al-Midhar’s] conversations, in fact, was reported to the FBI at the time, but neither the FBI nor the NSA investigated much further, officials now say.”

In The Looming Tower, Lawrence Wright reports that they even had a link chart up “on the wall of the bullpen” in Squad I-49 “showing the connections between Ahmed al-Hada’s phone and other phones around the world.”

“Had the line been drawn from the Hada household in Yemen to Hazmi and Mihdar’s San Diego apartment,” writes Wright, “al-Qaeda’s presence in America would have been glaringly obvious.”

But whose fault was it that the line wasn’t drawn? In his account Wright puts most of the blame on the CIA, but clearly in its investigation of the African Embassy bombings and what we now know to be their state of awareness of the importance of al-Midhar and that Sana’a (al Hada) safehouse, Squad I-49 of the FBI’s NYO ought to be held equally accountable for not connecting the dots.

Remember, by now, after keeping his name secret for two years, the FBI was pressing a worldwide manhunt for Khalid Shaikh Mohammed. The FBI had lost him twice, once at the Su Casa Guesthouse in Islamabad the day Yousef was busted in February 1995, and then in 1996 after Greg Scarpa Jr.’s patch-through at the M.C.C. had led the Feds to Doha, Qatar. But by 1999 KSM was in close contact with lead hijacker Mohammed Atta and two of the other 9/11 pilots: Marwan al-Shehhi (identified by the Able Danger operation) and Ziad Jarrah, who went on to commandeer the cockpit of UA Flight 93 that crashed in Pennsylvania. They were all living in an apartment together at 54 Marienstrasse in Hamburg, Germany with KSM’s number two Ramzi bin al-Shibh.

Described by the 9/11 Commission as the Hamburg “core group,” Atta, bin al-Shibh, al-Shehhi, and Jarrah met with bin Laden and Mohamed Atef in Afghanistan in late 1999, and two of them (bin al-Shibh and Atta) linked up with KSM in Karachi within weeks of the Kuala Lumpur summit.

The fact that the CIA had photographic evidence of the K.L. meeting’s attendees and didn’t share that with the FBI became an inter-agency flashpoint after 9/11. In The Cell, which he cowrote with ABC correspondent-turned-FBI spokesman John Miller, reporter Michael Stone even claimed that a June 11, 2001, meeting at the JTTF in New York, in which CIA agents refused to disclose details from the Malaysian meeting relating to the Cole bombing, ended up in a “shouting match.”

One of Stone’s key sources was none other than retired FBI agent Jack Cloonan.

When I interviewed Cloonan, who learned the details of the meeting immediately after it ended, he got much more specific, noting that Steve Bongardt, a veteran of the FBI’s TWA 800 investigation, had attended the meeting along with two other FBI agents.

“Dina Corsi, an FBI analyst from Headquarters comes up [to New York] with a CIA officer,” says Cloonan, “and they show three pictures of this meeting in Kuala Lumpur that CIA has known the significance of for months and they say they can’t share it with us.” Then “they ask, ‘Do you know anybody in these photographs?’ And Steve says, ‘Are these from the surveillance in Malaysia?’ But they won’t answer the question: ‘Can’t tell you.’ We’re talking about the so-called ‘wall’ now. Because the Cole investigation is a criminal investigation, ergo [according to Corsi], ‘We can’t share this information with you.’”

But Cloonan insists that there was no reason for Corsi, one of their own, to keep the contents of the photos secret. “Why are they there,” he wonders, if not to share the intelligence? “What sensitive sources and methods [would they be] compromising?” The so-called shouting match nearly turned into something more, as Cloonan tells it: “Bongardt gets so angry he almost goes over the table” at Corsi and the CIA officer. That meeting ultimately led Bongardt to write one of the most chilling and ironic e-mails in FBI history. Addressing the management at FBI Headquarters, he predicted that “Someday somebody will die—and, ‘wall’ or not, the public will not understand why we were not more effective.”

PROOF THAT THE FBI HAD ACCESS TO THE K.L. PHOTOS

But in our extensive interview on May 4, 2006, Cloonan gave me a stunning new piece of information that puts the alleged failure of the CIA to share the intelligence on the K.L. meeting in a whole new light. As it turns out, one of the key FBI agents in the FBI’s squad I-49 had seen some of the Malaysian summit pictures months before.

“Frank Pellegrino was in Kuala Lumpur” sometime following the summit, Cloonan admitted. “And the CIA chief of station said, ‘I’m not supposed to show these photographs, but here. Take a look at these photographs. Know any of these guys?’”

But as Cloonan described it, “Frank doesn’t know. He’s working Khalid Shaikh Mohammed,” and thus would not have recognized any of the faces.

When I suggested that Khalid Shaikh Mohammed may have been at the summit, Cloonan denied it, but then admitted that he wasn’t sure. Still, keep in mind—even if KSM, the man the FBI calls the 9/11 “mastermind,” did not attend this key planning session prior to the attacks, there was another significant al Qaeda face in the crowd that Pellegrino should have recognized immediately: Riduan Isamuddin, a.k.a. Hambali.

As chronicled by former CNN Manila bureau chief Maria Ressa in her compelling investigative book Seeds of Terror, “Khalid Shaikh Mohamed began visiting Malaysia starting in 1994 and tapped Hambali, whom he first met in Afghanistan, as his operative. He gave the seed money of about 95,000 ringgits, or $33,000, to Hambali to launch Jemaah Islamiyah’s operations there.”

Pellegrino had arrived in Manila within weeks of the fire in the Yousef-KSM bomb factory on January 6th, 1995. He was present at Camp Crame for most of Col. Mendoza’s interrogation of Abdul Hakim Murad, Yousef’s oldest friend, a pilot trained in 4 U.S. flight schools, who was to be the lead pilot in “the planes operation.” Mendoza and the PNP had documented Hambali’s importance as a key member of the al Qaeda cutout Konsonjaya. How was it possible that Pellegrino, a a top FBI agent who was now in Patrick Fitzgerald’s elite squad I-49 couldn’t connect the dots on Hambali, even after seeing the photographs of the KL summit from the CIA?

I wanted to ask Pellegrino that question, but he too refused to talk to me.

In any case, one lesson that the FBI should have learned from the Malaysian summit was just how well coordinated al Qaeda was. Far from the “loosely organized group” of Sunni Muslims somehow disconnected from the World Trade Center bombing, as Patrick Fitzgerald suggested in 2005, al Qaeda was a tightly integrated network with directions coming from the top down directly via bin Laden and Dr. al-Zawahiri. It was an international network capable of staging a summit conference, with operatives from half a dozen countries working together to plan acts of terror on three continents.

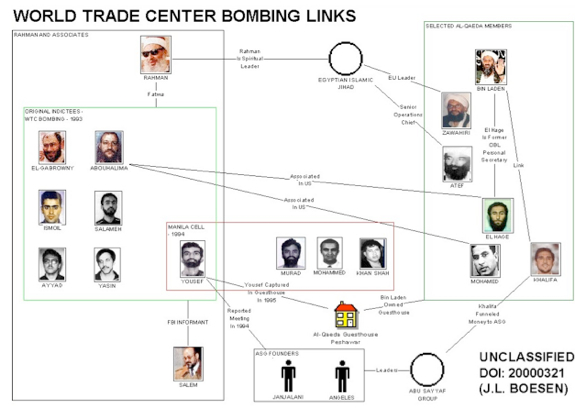

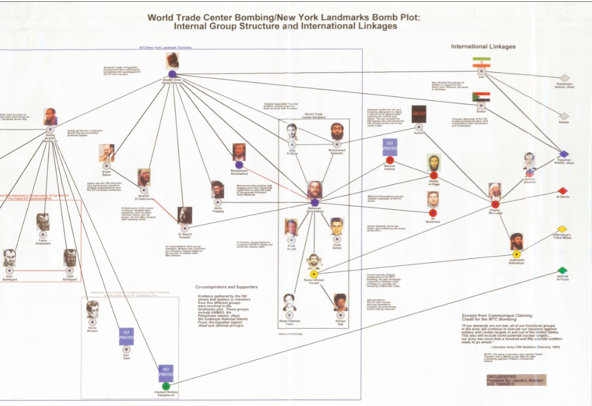

In its data-mining initiative, the Able Danger team at Fort Belvoir was making that same kind of connection with many of the same players. Eventually they would identify Aden Yemen as a key al Qaeda “hotspot” within days of the Cole bombing. In harvesting what eventually grew to 2.5 terabytes of data, they found linkages that corroborated my findings precisely: namely, that the New York cell of Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, trained by Ali Mohamed, was directly tied to al Qaeda’s leadership. The Able Danger findings corroborated what I had laid out in my last two books: that both attacks on the WTC, the 1993 bombing and the September 11 planes-as-missiles operation, were designed, funded, and directly controlled by al Qaeda’s leadership. In fact, the LIWA/DIA data miners went even further—putting Ali Mohamed and bin Laden’s brother-in-law Mohammed-Jamal-Khalifa in the al Qaeda inner circle.

THE SMOKING GUN LINK CHART

How do we know this? The connections were documented in a declassified link chart sent to me by Jacob L. Boesen who worked on many of the Able Danger charts. Declassified on March 21, 2000, the chart showed Ali Mohamed (with his photo from the Fort Bragg video) inside a box with bin Laden, Al-Zawahiri, Atef, Wadih El-Hage, and Mohammed Jamal Khalifa. That box linked to the Sheikh Rahman-Ramzi Yousef New York cell via the Egyptian Islamic Jihad and the Abu Sayyaf Group in the Philippines, which also linked to the Yousef-KSM-Murad-Wali Khan Manila cell responsible for the 9/11 attacks.

The chart not only vindicates my findings, but defies the conclusion later reached by Fitzgerald and Dietrich Snell, his SDNY colleague (a senior counsel on the 9/11 Commission) who determined the “origin of the plot” and pushed it forward two years to Afghanistan in 1996, removing Yousef from the plot and suggesting that at the time KSM was not even a member of al Qaeda—a conclusion that is almost comical in light of the documented evidence of al Qaeda’s control of the suicide-hijack plot.

That March 21, 2000, link chart, reproduced below, is the smoking gun document proving that the government understood both Ramzi Yousef and Ali Mohamed were involved with the multiple acts of mass murder and terror perpetrated by bin Laden’s network, from the killing of Rabbi Meier Kahane in 1990 forward. It’s a graphic representation of the FBI’s failures to contain all that horror, and it confirms my contention that Fitzgerald, Snell, Jamie Gorelick, and other key DOJ officials sought to hide the full truth behind the Justice Department’s failures from the American public.

A link chart designed by Jacob L. Boesen, a contract employee of Orion Scientific who designed most of the Able Danger Link Charts. This one, dated March 21st, 2000, just a few weeks before the Able Danger data was destroyed, shows Ali Mohammed in the inner circle with Osama bin Laden in a photo taken from a Fort Bragg training video.

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO OBLITERATING THE DOTS

“The Ali Mohamed link chart opens a whole new series of questions that have to be answered,” said former Congressman Curt Weldon (R-PA) one of the original backers of the LIWA unit at Fort Belvoir, and the man who first disclosed the story of the Able Danger operation to The New York Times in August, 2005.

Vice chairman of both the House Armed Services and the Homeland Security committees, Weldon said he was “blown away” by the data-mining capabilities of the Information Dominance Center as early as 1997, when he tapped the LIWA analysts for intelligence in preparation for a meeting in Vienna. At the height of the conflict in the former Yugoslavia, Weldon had heard that a certain Serb named Dragomir Kric had a back-channel to Serbian dictator Slobodan Milosevic, who was then holding three U.S. pilots as POWs in Belgrade. Weldon was about to chair a congressional delegation (CODEL) of Democrats and Republicans who would fly to Austria and meet with Russian leaders to try and broker a way out of the crisis.

“Before we left on that trip I wanted to know something about Kric, so I called [CIA director] George Tenet,” Weldon told me. “I said, ‘The Russians are convinced that this guy Kric can give us information that will allow us to get Milosevic to free those pilots. As the CIA Director, can you tell me something about him?’ Tenet called me back and gave me 2 or 3 sentences about Kric: that he was from a very influential family; that they had a bank and that he was tied in with the Communists in Russia. But the Agency didn’t know much else about him.”

Weldon then approached his contacts at Fort Belvoir, who did a quick data-mining run on the Serb. “They came back to me with ten pages of information about this man,” said Weldon. “The fact that he owns the apartment building where Milosovic lives. The fact that their wives are very close. An incredibly detailed profile that I got almost overnight from this tiny under-funded operation on an army base, when our own CIA didn’t seem to have a clue who Kric was.”

Weldon says that after he returned from meeting the Russians he got phone calls from both the FBI and the CIA. So many members of his congressional delegation had raved about the LIWA report on Kric that the Agency and the Bureau both asked where he was getting his intelligence.

“I met with them on a Monday afternoon,” said Weldon. “One FBI agent and a CIA case officer in my office on the Hill, and they were both stunned. Neither of them had even heard about LIWA or this type of data-mining capability.”

Years later, when he heard that LIWA had been enlisted by the Special Operations Command to harvest intelligence on al Qaeda—and that they’d made the startling links to the blind Sheikh and the four 9/11 hijackers—Weldon said he wasn’t surprised.

“This was intelligence that the Able Danger operation got in early 2000 that absolutely, if properly acted upon, could have stopped the 9/11 plot cold,” he insisted.

Maj. Eric Kleinsmith, the former chief of intelligence at LIWA, seemed to agree. “We were able to collect an immense amount of data for analysis that allowed us to map al Qaeda as a worldwide threat with a surprisingly significant presence within the United States.” he said at a 2005 Senate hearing.

But by April 2000, Kleinsmith and other LIWA personnel on the Able Danger project were told by DOD lawyers that this vast amount of open source data may have violated Executive Order 12333, an intelligence directive signed in 1981 by President Ronald Reagan after the Senate and House hearings into CIA domestic spying abuses in the 1970s.

“The EO,” as it’s known, was designed to prevent the Pentagon from storing data indefinitely on “U.S. persons,” a term defined to include American citizens, U.S. corporations; even permanent resident aliens.

“’U.S. person’ information is something that we are skittish about in the Defense Department,” said William Dugan, Assistant Secretary of Defense in the George W. Bush administration, in testimony before that same Senate hearing. “We follow the rules strictly on it.”

As a result of the Pentagon’s alleged concerns about the 2.5 terabytes of Able Danger data containing information on “U.S. persons” along side al Qaeda terrorists, Kleinsmith says that he and his deputy got a direct order:

“I, along with CW3 Terri Stephens, were forced to destroy all the data, charts, and other analytical products that we had not already passed on to SOCOM related to Able Danger.”

“Imagine,” said Weldon. “You’ve got this embarrassment of riches with probative al Qaeda intelligence—the names of four of the September 11th hijackers in the spring of 2000, almost a year and a half before the attacks. You’ve got Atta, the lead hijacker on the American flight that hits the North Tower of the Trade Center; al-Shehhi, who sends UA 175 into the South Tower; and al Midhar and al Hazmi, who hit the Pentagon. They’re identified in open-source data and then, under the guise of conforming to this EO, it gets destroyed. Well, guess what? There was no legal justification for it whatsoever.”

Indeed, EO 12333 has ten provisions allowing for the retention of data including “Information that is publicly available” and “Information obtained in the course of a lawful foreign intelligence, counterintelligence . . . or international terrorism investigation.”

“All of the initial Able Danger data runs involved open-source, non-classified data,” says Lt. Col. Anthony Shaffer, the DIA liaison to the Able Danger operation, “and clearly we were dealing with terrorism. So the excuse that came down from DOD, that this data had to be destroyed in order to protect so-called ‘U.S. persons,’ just doesn’t wash.”

“All of the initial Able Danger data runs involved open-source, non-classified data,” says Lt. Col. Anthony Shaffer, the DIA liaison to the Able Danger operation, “and clearly we were dealing with terrorism. So the excuse that came down from DOD, that this data had to be destroyed in order to protect so-called ‘U.S. persons,’ just doesn’t wash.”

“That’s what makes what happened in April 2000 all the more outrageous,” said ex- Cong. Weldon. “And as we’ve looked into this, it has turned into a cover-up that’s bigger than Watergate. Richard Nixon lost the presidency over a third-rate burglary. This was an affirmative destruction of data that could have helped save the lives of 3,000 people.”

THE MUSCLE HIJACKERS AND THE ONE-LEGGED TERRORIST

It’s not particularly surprising that the Able Danger data sweep of open-source information would have picked up the soon-to-be muscle hijackers al-Midhar and al-Hazmi. Their visibility in the U.S. was so high in the eighteen months prior to their airborne assault on the Pentagon that the FBI’s failure to detect them seems to border on gross negligence—even with the CIA’s refusal to share the intel.

As early as 1999, while monitoring phone calls at the Sana’a Yemen safe house, the NSA picked up references to Khalid al-Midhar, Nawaf al-Hazmi and his brother Salem, who would also become one of the suicide hijackers on 9/11. The FBI knew about that safe house. In fact, the location was the result of a lead uncovered by their own criminal investigation of the Embassy bombings. And yet the Bureau seemed in no hurry to establish their own wiretaps on the Sana’a residence or to insist on copies of NSA or CIA intercepts—cooperation one would expect the FBI to demand in the investigation of 224 murders in East Africa.

That wiretap of the home of Khalid al-Midhar’s brother-in-law led the CIA to monitor the summit in Kuala Lumpur, but even before that there is evidence that al-Midhar and al-Hazmi had entered the U.S.

In a Pulitzer Prize-winning story for the Washington Post in late September 2001, Amy Goldstein reported that the two hijackers actually showed up at the Parkwood Apartments, a townhouse complex in San Diego, in late 1999. This San Diego connection would prove key, because after the two hijackers returned to the U.S. and slipped past a Watch List in January 2000, they ended up living in rooms rented to them by a San Diego FBI informant.

Tracked to the K.L. summit, al-Midhar’s passport was copied in Dubai and sent to the CIA’s Alec Station (where the FBI had an agent in residence). He was later photographed at the K.L. summit by the Malaysian Special Branch. On January 8th, when the conference ended, al-Midhar flew with al-Hazmi to Bangkok, Thailand—both of them using their own names on the flight manifests. Sitting next to them in a three-seat configuration was Khallad bin Atash, the one-legged Saudi who had sent al-‘Owali to his intended death in Nairobi. Atash had recently attempted to blow up the Aegis-class guided missile destroyer, the U.S.S. The Sullivans – a failed al Qaeda action that was a precursor to the Cole bombing.

At that point, the FBI was doing a full-court press on the Embassy bombing investigation. Al-‘Owali’s tip on the Sana’a safehouse had led to the discovery of bin Atash by the Malaysians. The fact that Special Agent Frank Pellegrino of Squad I-49 had seen pictures of the K.L. summit meant that the Bureau was in the loop. And yet following the January 8th flight, both the FBI and the CIA reportedly lost all three terrorists in the Thai capital. Worse, despite having identified al-Midhar as an al Qaeda associate, and realizing that he had a U.S. multi-entry visa, the CIA never added his name to the TIPOFF watch list of some 70,000 suspected terrorists.

As such, using their own names, al-Midhar and al-Hazmi jetted from Bangkok to Los Angeles on January 15th. There they were met by Omar al-Bayoumi a Saudi , suspected of being an intelligence officer, who had visited the Saudi consulate in L.A. the same day. After three weeks the two would-be hijackers moved to San Diego, where they lived openly for the next five months. During that period al-Bayoumi helped them get settled, finding them an apartment across from where he lived.

It was later reported by Newsweek and the Washington Times that al-Bayoumi may have been the recipient of funds sent ito his wife indirectly from Princess Haifa bin Faisal, wife of the then-Saudi ambassador to the U.S., Prince Bandar. According to terrorism analyst Paul Thompson in historycommons.org, Princess Haifa began sending cashier’s checks to Majeda Dwiekat, the Jordanian wife of one Osama Basnan, a Saudi living in San Diego. Basnan’s wife then reportedly signed many of the checks over to the wife of Omar al-Bayoumi. Prince Bandar, who later stepped down as U.S. ambassador, emphatically denied any impropriety at the time the check scandal broke. But according to Thompson:

Within days of bringing them from Los Angeles, al-Bayoumi throws a welcoming party that introduces them to the local Muslim community. One associate later says that al-Bayoumi party “was a big deal . . . it meant that everyone accepted them without question.” He also introduces hijacker Hani Hanjour to the community a short time later. He tasks an acquaintance, Modhar Abdallah, to serve as their translator and help them get driver’s licenses, Social Security cards, information on flight schools, and more.”

THE HIGH VISIBILITY OF “DUMB AND DUMBER”

During their early months in San Diego, Al-Midhar and al-Hazmi proved to be the antithesis of low-profile sleepers. They took flight lessons at the Sorbi Flying Club, bought season passes to Sea World, played soccer in a local park, and interacted with many members of the Muslim community. Al-Midhar bought a 1998 Toyota Corolla for $3,000 and registered it with the California DMV. After moving into a two-story town home at 6401 Mount Ada Road, Al-Hazmi got a telephone. He even had his full name listed in the phone directory.

But the two Saudis showed little talent for flying. Announcing that they wanted to learn to fly Boeing jumbo jets, they trained on twin-engine Cessnas, and demonstrated so little aptitude in the cockpit that their flight instructor, Rick Garza, nicknamed them “Dumb and Dumber.”

Throughout the spring and summer of 2000, the National Security Agency, which began monitoring al-Midhar’s brother-in-law’s home in Yemen in 1998, picked up multiple intercepts between San Diego and the safe house. As it turned out, al-Midhar’s wife was about to give birth in the year 2000. But the NSA later claimed that it didn’t know that the calls from al-Midhar originated in the U.S. It wasn’t until after 9/11 that the Feds realized that Ramzi bin al-Shibh, KSM’s number two on the entire planes-as-missiles operation, was al-Midhar’s cousin.

On June 3, 2000, lead hijacker Mohammed Atta arrived in the U.S., and rented a room in Brooklyn, New York. He listed the same address in Hamburg, Germany: 54 Marienstrasse, where he’d been living with hijacker-pilots al-Shehhi and Ziad Jarrah. In San Diego, neighbors of al-Midhar and al-Hazmi claimed that Atta and Hani Hanjour, the pilot of AA 77, visited them. There was a report that Hanjour actually roomed with them for a time, but didn’t stay.

“Later, the Pentagon denied that the Able Danger data mining had uncovered Atta, al-Shehhi, and the two San Diego hijackers” in early 2000,” says former Cong. Weldon. “But you can see how visible they were at this time. We’re not talking needles in haystacks here. With al-Midhar you’ve got a terrorist with known al Qaeda connections through the Yemeni safe house. Atta shows up in Brooklyn, and the LIWA people find out he’s linked to the al Farooq mosque, where the blind Sheikh ran his New York cell. This isn’t rocket science. These killers in our midst were highly visible.”

THE FBI BLOWS ITS BEST CHANCE

Despite the FBI’s ongoing complaint that they were consistently blindsided by the CIA on the presence of al-Midhar and al-Hazmi, both at the K.L. meeting and in their U.S. entry, the Bureau deserves equal criticism for its failure to locate the two muscle hijackers. Why? Because by the summer of 2000 they moved into the Lemon Grove section of San Diego, renting rooms from Abdussattar Shaykh, a local Muslim leader who was also an FBI informant In fact, Shaykh was considered so important to the Bureau that he was later described as a “tested” undercover “asset.” Newsweek’s Michael Isikoff first broke that story after 9/11, and terrorism researcher Paul Thompson has advanced it on his website, historycommons.org. Citing Isikoff’s groundbreaking reporting, Thompson completed the mosaic of what must go down as one of the most profound FBI failures in the years leading up to 9/11. Because of the significance of the lapse, we are reproducing Thompson’s account in full:

While hijackers Nawaf al-Hazmi and Khalid al-Midhar live in the house of an FBI asset, Abdussattar Shaykh, the asset continues to have contact with his FBI handler. The handler, Steven Butler, later claims that during the summer Shaykh mentions the names “Nawaf” and “Khalid” in passing and that they are renting rooms from him. On one occasion, Shaykh tells Butler on the phone he cannot talk because Khalid is in the room. Shaykh tells Butler they are good, religious Muslims who are legally in the U.S. to visit and attend school.

Butler asks Shaykh for their last names, but Shaykh refuses to provide them. Butler is not told that they are pursuing flight training. Shaykh tells Butler that they are apolitical and have done nothing to arouse suspicion. However, according to the 9/11 Congressional Joint Inquiry, he later admits that al-Hazmi has “contacts with at least four individuals [he] knew were of interest to the FBI and about whom [he] had previously reported to the FBI.” Three of these four people are being actively investigated at the time the hijackers are there. The report mentions Osama Mustafa as one, and Shaykh admits that suspected Saudi agent Omar al-Bayoumi was a friend. The FBI later concludes that Shaykh is not involved in the 9/11 plot, but they have serious doubts about his credibility.

After 9/11 he gives inaccurate information and has an “inconclusive” polygraph examination about his foreknowledge of the 9/11 attack. The FBI believes he has contact with hijacker Hani Hanjour, but he claims not to recognize him. There are other “significant inconsistencies” in Shaykh’s statements about the hijackers, including when he first met them and later meetings with them. The 9/11 Congressional Inquiry later concludes that had the asset’s contacts with the hijackers been capitalized upon, it “would have given the San Diego FBI field office perhaps the U.S. intelligence community’s best chance to unravel the September 11 plot.”

After 9/11, when the Congressional Joint Inquiry discovered Shaykh’s identity and issued a subpoena for him to testify, Attorney General John Ashcroft refused to allow his agents to serve it. Sen. Bob Graham, the Democrat who co-chaired the Joint Inquiry, used the term “cover up” to describe the stonewalling by Justice in refusing to disclose the depth of Shaykh’s apparent duplicity.

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE ABLE DANGER PART TWO

In the summer of 2000, there was another significant opportunity for the U.S. intelligence community to interdict Ramzi Yousef’s suicide-hijacking plot. Although the Able Danger unit’s initial data run was ordered destroyed, the Army’s Special Operations Command set up a follow-up unit. Contracted out to Raytheon’s Intelligence and Information Systems facility at Garland, Texas, several of the key LIWA data miners were brought over to do a new “harvest” of open-source material on al Qaeda. Among them were Dr. Ellen Preisser and Jacob L. “Jay” Boesen, who continued to produce link charts for the operation.

“By late summer, that second Able Danger configuration had re-confirmed the previous hits on Atta, al-Midhar, al Hazmi and al-Shehhi,” says Lt. Col. Anthony Shaffer, “but they also identified Aden Yemen at one of the top three al Qaeda hotspots in the world.”

Again, this connect wasn’t surprising, since the CIA had earlier tracked Khallad bin Atash, the one-legged Embassy bombing plotter with heavy Yemeni ties. Also, another attendee of the Malaysian summit, Fahad al-Quso, was based in Aden.

At this point, Shaffer, the DIA’s liaison to the Able Danger operation, was asked by Special Operations Command to contact the FBI.

“We had been working a parallel operation to the FBI looking at The 17th of November, a terrorist organization in Athens,” says Shaffer. “The FBI had asked us for help in preparation for the Olympics and we were actually tasked to use the same basic data mining methodology. It was because of that link that SOCOM came to me and said, ‘Would you please broker meetings between us and FBI regarding passing, some of the al Qaeda information?’ So I went to my FBI contact on The 17th of November and asked to meet with the agents in the WFO [Washington Field Office] who worked bin Laden.”

Shaffer says that three separate meetings with Bureau agents were scheduled between the summer and September 2000. But each meeting was cancelled “on the advice of SOCOM attorneys.” The reason? “SOCOM lawyers would not permit the sharing of the ‘U.S. person’ information regarding terrorists located domestically, due to ‘fear of potential blowback,’ should the FBI do something with the information and something should go wrong.” That’s what Shaffer ultimately reported to a House committee investigating the Able Danger data destruction.

Until recently, both Shaffer and ex-Cong. Weldon believed that Pentagon officials had ordered the FBI meetings cancelled for the same reason they gave to explain the destruction of the 2.5 terabytes of data: concern that EO 12333 might have been violated. But in light of my discovery of J.L. Boesen’s March 21, 2000 link chart showing Ali Mohamed in the al Qaeda inner circle, both Weldon and Shaffer have come to suspect another reason for the data destruction.

“I can tell you that right after the story broke on Able Danger,” says Shaffer, “people from the army came to me and said, ‘We don’t want to be blamed for 9/11.’ And I couldn’t understand that position back then, Because why would the army be blamed? If anything, with the LIWA data mining, we had been ahead of the curve, and we had done our best to sound the alarm. But then, seeing this link chart with Ali Mohamed’s picture coming a week or so before the data was destroyed, gave me a sense that there could be another explanation.”

“Imagine if you are a high ranking general in SOCOM,” said Weldon. “And you have authorized this extraordinary data mining operation which turns up amazing evidence of an al Qaeda presence in the U.S. in the spring of 2000. Then the LIWA people show you a link chart with a picture of this fellow Ali Mohamed so close to bin Laden. And then you ask who he is, and you find out straightaway that he was an al Qaeda spy who was active-duty Army, and that he had infiltrated the JFK Special Warfare School at Fort Bragg back in 1987. Not only that, but he stole classified documents on SOCOM troop locations. He may have even trained al Qaeda cell members in Somalia who helped take down those two Blackhawks in 1993. He definitely took the pictures of the Nairobi Embassy and precisely targeted the suicide truck bomb that killed hundreds of people in ’98. He was bin Laden’s personal security advisor. That is the ultimate example of blowback. How do you think an Army general would react to that kind of news? That the Green Berets had let an al Qaeda spy into their midst when the senior Bush was in the White House. It is entirely possible that the Pentagon did a damage assessment in April of 2000 and hit the panic button. They just used EO 12333 as the excuse.”

Weldon, a loyal conservative, came to believe that the suppression of intelligence on al Qaeda was a scandal that transcended political administrations, parties, and agencies.

“From the FBI to the DIA and the CIA there has been an affirmative attempt to cover up the mistakes of the past—of which Ali Mohamed was perhaps one of the most egregious examples,” he said. “The consequence was that as we got closer to 9/11 we weren’t getting smarter about the al Qaeda threat, we were having blinders put on. Key dots were being hidden for the oldest excuse inside the Beltway: CYA—the avoidance of embarrassment.”

The situation got so bad that at one point Tony Shaffer says he saw a series of link charts from the original LIWA data runs in which “yellow stickies” had been pasted over the pictures of key al Qaeda operatives like Mohammed Atta, on the orders of SOCOM lawyers.

“THE CLOSE-TO-ABSOLUTELY-PERFECT RECORD”

In September 2000, on the twentieth anniversary of the NYO’s Joint Terrorism Task Force, representatives of the seventeen federal, state and local law enforcement agencies that made up the JTTF assembled for a celebration. In the course of the party, SDNY U.S. Attorney Mary Jo White praised the FBI’s flagship task force for what she called a “close-to-absolutely-perfect record of successful investigations and convictions.” Later, White wrote an essay calling the JTTF members the “true heroes of the city.”

“For twenty years,” wrote White, “the JTTF has been a huge success story, measured both in terms of arrests and convictions of terrorists that the public knows about and (even more important) in the mostly unseen work of the JTTF, in detecting and preventing terrorist acts that do not result in prosecutions or publicity.”

“For twenty years,” wrote White, “the JTTF has been a huge success story, measured both in terms of arrests and convictions of terrorists that the public knows about and (even more important) in the mostly unseen work of the JTTF, in detecting and preventing terrorist acts that do not result in prosecutions or publicity.”

Naturally, in assessing the JTTF’s “next to perfect record,” White avoided certain details, such as how the JTTF’s boss, Carson Dunbar, had thwarted the FBI’s best chance of stopping the first attack on the Twin Towers by alienating Emad Salem and failing to authorize the surveillance he pleaded for on two of Ali Mohamed’s trained cell members Abouhalima and Salameh.

She left out the fact that her star prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald and his elite Squad I-49 had advance warning of the African embassy bombings, including wiretaps on the key cell members, and the fact that Ali Mohamed, one of the cell’s ring leaders, had worked as the FBI’s own west coast informant. She skipped over the fact that Special Agent Frank Pellegrino had seen the surveillance photos of the 9/11 Malaysian summit and failed to recognize either Hambali or Khallad bin Atash, who was weeks away from wreaking bin Laden’s next act of “havoc” for the jihad.

With the same arrogance Special Agent John Zent had shown in flashing his Bureau I.D. to intimidate those Fresno sheriff’s detectives in 1992, White was trading on the myth—often stoked by the media—that “the best and the brightest” in the FBI’s two bin Laden offices of origin would keep New Yorkers safe from Osama bin Laden’s terror war. There was even a hint of irony in the location of the JTTF’s anniversary party, the same place where Neal Herman’s retirement party had been held on September 11, 1999: the spectacular 50,000 square foot restaurant Windows on the World, located on the top floor of the World Trade Center’s North Tower.

As the Feds partied on, bin Laden’s jihadis were working day and night from Afghanistan to San Diego to Brooklyn to bring those Towers down. None of the revelers seemed to remember Ramzi Yousef’s 1993 warning, found on Nidal Ayyad’s computer, that his “calculations were not very accurate” but that the Trade Center would again be a target. Or Murad’s warning to SA Frank Pellegrino that: “Ramzi wanted to return to the U.S.” to attack the Towers a second time. Or even Yousef’s chilling warning during that late night flyby of the WTC in 1995 that the Trade Center might still be vulnerable.

BIN LADEN’S NEXT WARNING

Perhaps sensing how persistently U.S. intelligence agencies underestimated their resolve, the terrorists of al Qaeda were very good about telegraphing their moves. Within weeks of that JTTF party, SOCOM lawyers had cancelled Lt. Col. Tony Shaffer’s last chance to share the Able Danger intelligence with the FBI. But while the Pentagon seemed unwilling to have the FBI connect the dots, Osama bin Laden himself was using the world media to call his next play.

On September 21st, 2000, he issued another fatwa, this one released to Al Jazeera, the Arabic television network, on videotape. As a hint of al Qaeda’s next flash point, the Saudi terror leader brandished a jewel-encrusted Yemeni dagger. He also reminded the Feds of al Qaeda’s loyalty to the spiritual leader of the New York cell—blind Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, whom the Able Danger data-miners had clearly linked to al Qaeda just months before.

Bin Laden’s last major fatwa in 1998, the “Jihad against Jews and Crusaders, had been signed by Ayman al-Zawahiri and Abu-Yasir Refai Taha, who had taken over for the jailed blind Sheikh as head of the al Gamma’a Islamiyah. Now, on this tape, bin Laden was flanked by Taha and al-Zawahiri again; and next to them sat Mohammed Abdel Rahman, one of the blind Sheikh’s sons.

After a rambling speech, the younger Rahman urged their followers to “avenge your Sheikh” and “go to the spilling of blood.” Then, almost as if to thumb his nose at the New York FBI, bin Laden himself told the faithful to remember El Sayyid Nosair. For those in the Bureau who continued to insist that there was no connection between the two attacks on the Trade Center, this video should have been proof positive that they were wrong. Osama bin Laden was personally invoking the name of the very al Qaeda operative—trained by Ali Mohamed—who had spilled the first al Qaeda blood on U.S. soil with the murder of Rabbi Kahane almost a decade earlier.

Yet a number of top U.S. intelligence analysts, including former CIA director James R. Woolsey, continued to insist that Saddam Hussein had been the primary force behind the 1993 World Trade Center attack, and that Ramzi Yousef had been an Iraqi agent. It was a completely specious theory, but one that many in the Bush administration would seize upon to help justify the invasion of Iraq in March 2003.

In any case, bin Laden’s video fatwa with the Yemeni dagger should have been another profound warning to the Feds. “Here he was flaunting his U.S. indictment, saying we will get you,” recalls a former FBI agent who worked terrorism. “And a few weeks later he did.”

On October 12th, al Qaeda suicide bombers, piloting a small inflatable dinghy, drove it into the side of the U.S.S. Cole, an advanced guided missile destroyer docked for refueling in Aden, Yemen. The blast blew a four-story hole in the ship and killed seventeen U.S. sailors.

“We had data just days before the Cole bombing,” says Lt. Col. Shaffer, “that Aden was a hotspot. I communicated this information to SOCOM and they reportedly passed it on to CENTCOM, but for unknown reasons the threat assessment was not communicated to Commander Lippold, the skipper of the Cole.”

“I met with Kirk Lippold, whose career has basically ended,” said Weldon in a February 2006 speech. “He said to me, ‘I had three choices that day. I could have refueled at sea. I could have refueled at a different city. If I would have known there was any potential problem in Aden, I would not have gone into port. But no one told me.’ Seventeen sailors came home in body bags.”

In another sad irony on the lead up to 9/11, it turned out that the National Security Agency’s tap on the Sana’a Yemen safe house of Khalid al-Midhar’s brother-in-law had yielded up to a half dozen calls to the U.S. even after the Cole bombing. But according to Josh Meyer, reporting in the Los Angeles Times, “the NSA didn’t disclose the existence of the calls until after Sept. 11th.”

FINALLY, THE CONTRITE SPY

Eight days after the Cole bombing, Ali Mohamed stood stoop-shouldered before Judge Leonard B. Sand in that Southern District courtroom. Patrick Fitzgerald stood at his side with four other assistant AUSAs, including Michael Garcia, who convicted Ramzi Yousef for the Bojinka plot, and Andrew McCarthy who had worked with Fitzgerald to put the blind Sheikh away. The record does not reflect whether Dietrich Snell, who co-prosecuted the Bojinka case, was also present, but Mary Jo White was on hand, along with Jack Cloonan, who now says that Ali finally confessed to the embassy bombings eighteen months after his arrest in September 1998.

But the “confession” came only after the Feds agreed to give Ali the “exit strategy” he’d been angling for all along. “Ali paints himself into a corner,” says Cloonan, “and he just basically runs out of room. His frustration level is increasing and it is weighing on him physically and mentally. On the day in question when he ultimately admits to what his role was, it is Pat [Fitzgerald who] brings him up to the precipice. I know at one point that day I said to Ali words to this effect:

But the “confession” came only after the Feds agreed to give Ali the “exit strategy” he’d been angling for all along. “Ali paints himself into a corner,” says Cloonan, “and he just basically runs out of room. His frustration level is increasing and it is weighing on him physically and mentally. On the day in question when he ultimately admits to what his role was, it is Pat [Fitzgerald who] brings him up to the precipice. I know at one point that day I said to Ali words to this effect:

‘I’m not going to look at you as any less of a human being. You deserve some peace, because ultimately that’s what we all want, isn’t it? Because you may have done some things that I don’t particularly agree with, or that frankly might have been deadly or in violation of the law [but that] doesn’t mean that I’m going to treat you any different. You have to find a way out and we’re giving you a way out. Do you understand that? We’re giving you a way out. We can literally lift this 900-pound gorilla off of your shoulders. What you need is an exit strategy. You need to feel as though you’re not being an apostate, that you’re a traitor to the cause, that you’ve disgraced yourself, that you’ve disgraced Islam. Think long and hard about what we said. This man over here, Mr. Fitzgerald, has treated you very, very fairly. You know that. Do you know that he’s a powerful man? My colleague Dan [Coleman] here has done similarly. He’s talked to you about his family. He’s talked to you about the importance of family and how they’re going to help you. I think what you need to do is sit with your attorney and you need a private moment to pray. We’re going to go outside, and when I come back in, and we all come back in, things are going to be different.’”

Cloonan says that Mohamed then consulted with his lawyer, James Roth.

“About ten minutes into this, Jim Roth came outside and said, ‘He’s ready. He did it.’

“We walked in and sat down. Ali was physically shaken. He slumped in his chair, head down, literally a shell of the man that we sort of knew, tears in his eyes. He said, ‘This is what I did.’ Then, I remember writing down the notes. He was saying, ‘Yes Mohamed Atef asked me with Zawahiri and bin Laden’s blessing to do the surveillance on the U.S. embassy in Nairobi.’

“I had to make sure I heard that right. ‘This is what I did, this is who I did it with, this is how I did it, and I did other things. Everything that I’ve told you up to this point has been a lie. I am telling you the truth from here on out.’

“I think we had to stop at that point.” says Cloonan, “because I think we were all—Ali, Jim, Pat, Dan and myself—I think we were in mixed emotions. We knew the significance of [the confession] in our world. It may not have meant much to everybody else, but the system worked. We were successful. Slow, maybe, but successful.”

Fitzgerald and the agents of Squad I-49 may have been successful in finally pulling the truth out of Mohamed with respect to the Embassy bombing. But it had come years too late. They had been outflanked by the al Qaeda spy for years, seemingly incapable of detecting his agenda when he was “fully operational.”

Ali Mohamed was living proof that the FBI, under three presidential administrations, had been deceived by an asset expert at playing one intelligence agency off against another, even as he betrayed his adopted country for the jihad. Worse, the price the Feds paid for Ali’s so called “cooperation” was a plea deal that allowed him to avoid execution and life behind bars. In an echo of ex- agent Jack Cloonan’s reference to “an exit strategy,” Judge Sand actually discussed the possibility that if Ali Mohamed did not get the maximum sentence, he would one day be granted “supervised release.”

Ali Mohamed was living proof that the FBI, under three presidential administrations, had been deceived by an asset expert at playing one intelligence agency off against another, even as he betrayed his adopted country for the jihad. Worse, the price the Feds paid for Ali’s so called “cooperation” was a plea deal that allowed him to avoid execution and life behind bars. In an echo of ex- agent Jack Cloonan’s reference to “an exit strategy,” Judge Sand actually discussed the possibility that if Ali Mohamed did not get the maximum sentence, he would one day be granted “supervised release.”

THE COURT: Your offer is to plead guilty to five counts charging you with conspiracy to kill nationals of the United States, conspiracy to murder, kidnap and maim at places outside of the United States, conspiracy to murder, conspiracy to destroy buildings and property of the United States, and conspiracy to destroy national-defense utilities of the United States. Do you understand that pursuant to the relevant statutes, conviction on those five counts would subject you to a total maximum sentence of incarceration of life imprisonment plus any term of years. Do you understand that you would be subject to that potential sentence?

MOHAMED: Yes, your honor.

THE COURT: Do you understand that in addition to that, you would be subject to a term

of supervised release of five years on Counts One, Two, Three and Five and three years’ supervised release on Count Six? Do you understand that?

MOHAMED: Yes, your honor.

The details of Ali Mohamed’s deal remain secret to this day. But at least one knowledgeable attorney—David Runhke, who represented another of the embassy bombing defendants—has concluded that his arrangement with the Feds was clearly in Ali’s favor. “

“Mohamed has made some kind of deal with the government,” Ruhnke believes, “that will surely have him out of prison on some date certain that he knows about.”

THE UNDISCOVERED SLEEPERS

With Ali Mohamed’s plea, the curtain fell on the career of one of world history’s most audacious and accomplished spies. But the story was far from over. Having failed, before the fact, to extract from Mohamed the details of the embassy bombing plot he had planned and helped to supervise, Patrick Fitzgerald and his Southern District colleagues now had the potential of exposing hundreds of al Qaeda agents who had burrowed into the U.S.—many with Ali’s own help.

In the year 2000, Benjamin Weiser, the New York Times reporter who has done perhaps the most extensive newspaper reporting on Mohamed, sought to unseal a series of summaries that shed additional light on what the Egyptian agent was willing to tell the Feds. In one of the proffer sessions, according to Weiser, an FBI report stated that Ali “knows, for example, that there are hundreds of ‘sleepers’ or ‘submarines’ in place who don’t fit neatly into the terrorist profile. These individuals don’t wear the traditional beards and they don’t pray at the mosques.”

In his 1999 confession to Egyptian authorities, Ali’s Santa Clara protégé Khalid Dahab had admitted that he and Mohamed had recruited at least ten sleepers in Santa Clara alone. Now, after Ali’s deal with the Feds, the question was just how many other al Qaeda agents there were in this country and when he would give them up.

So far, the evidence suggests that he hasn’t.

As this investigation has revealed for the first time, almost six years after entering that guilty plea, Ali Mohamed has yet to be sentenced. His own wife, Linda Sanchez, told me that directly, and it was confirmed by Jack Cloonan (at right). Yet we can say for certain that even today, as he remains in witness protection somewhere in the New York area, Ali Mohamed has never fully betrayed Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden, or the jihad which he was willing to kill for.

As this investigation has revealed for the first time, almost six years after entering that guilty plea, Ali Mohamed has yet to be sentenced. His own wife, Linda Sanchez, told me that directly, and it was confirmed by Jack Cloonan (at right). Yet we can say for certain that even today, as he remains in witness protection somewhere in the New York area, Ali Mohamed has never fully betrayed Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden, or the jihad which he was willing to kill for.

How do we know this? Because if Ali had ever given the Feds the name or location of a single one of those sleepers, they would have been arrested or indicted by now.

“You might argue that in the beginning, the Bureau might have kept some of the names secret, if they had them, for intelligence purposes—to get a sense of the larger network that might be operational here,” says a former agent in the NYO. “But they certainly wouldn’t have held off on arrests after 9/11, and certainly not now, six years after Ali’s confession.”

“The fact that he knows where tens, maybe hundreds of al Qaeda agents or sympathizers are, burrowed into America like moles, just goes to show you that we still don’t have the full truth from Ali Mohamed, “ says the agent. “Keep in mind that he was finally arrested three years before 9/11. If he’d given up a single one of those sleepers, it might have helped interdict the plot.”

But in the high-stakes poker game between captured terrorist and an FBI anxious for him to sell out in return for leniency, Ali Mohamed got much more than he was ever willing to give.

“His hold card, and the reason he’s still not been sentenced,” says a defense lawyer close to the embassy bombing case, “is the sheer embarrassment that the Justice Department would face if somebody like me ever got a crack at Mohamed on the stand.”

As the Embassy bombing trial approached, would Ali Mohamed, the Feds’ star witness, take the stand? Some senior reporters who covered the Justice Department suggested he would. But, as always, Ali Mohamed possessed an infinite capacity for surprise.

WILL WE EVER KNOW THE FULL TRUTH?

We certainly know more of it now. The Ali Mohamed story offers a stunning illustration of how often the FBI and DOJ dropped the ball in underestimating the al Qaeda threat. The findings of the Able Danger team underscored the connections between al Qaeda’s leadership and the Yousef/Rahman New York cell, and reinforced evidence disclosed by the Justice Department’s own inspector general that the Feds should have had plenty of advance warning about the presence in the U.S. of key hijackers like al-Midhar and al-Hazmi in early 2000, more than a year and a half before the 9/11 attacks.

But on September 18, 2006, the inspector general for the Department of Defense decided to tell the Able Danger story another way. In a heavily redacted ninety-page report, the IG rejected claims by Lt. Col. Anthony Shaffer, Navy Capt. Scott Phillpott, and former Cong. Curt Weldon that the Able Danger unit had tracked those two muscle hijackers, along with Marwan al-Shehhi and Mohammed Atta, prior to 9/11.

“We concluded that prior to Sept. 11, 2001, Able Danger team members did not identify Mohammed Atta or any other 9/11 hijackers,” the report stated. “While we interviewed four witnesses who claimed to have seen a chart depicting. . . . Atta and possibly other terrorists or ‘cells’ involved in 9/11, we determined that their recollections were not accurate.”

Further, the report concluded that “DIA officials did not reprise against LTC Shaffer, in either his civilian or military capacity, for making disclosures regarding Able Danger.”

Reaction from ex-Cong. Weldon was swift:

“The DOD IG cherry picked testimony from witnesses in an effort to minimize the historical importance of the Able Danger effort,” said Weldon. “The IG narrowly focused their investigation on the witnesses’ recollections of the 9/11 hijackers and a chart. The report trashes the reputations of military officers who had the courage to step forward and put their necks on the line to describe important work they were doing to track al-Qaeda prior to 9/11.”

Though the names of most witness were redacted, it’s clear that the DOD IG’s office conducted multiple interviews with Shaffer, Phillpott, and Dr. Ellen Preisser, who worked on the Able Danger team at LIWA and Garland, Texas. While each of them repeatedly insisted they had seen Atta’s photo and/or name in the early Able Danger data harvest, the IG’s investigators seemed bent on impeaching their accounts.

Potentially the most damaging allegation, singled out in the coverage of the IG’s report in the Washington Post, had to do with Phillpott’s allegedly varying accounts of Atta’s picture.

“The report concludes that Philpott may have exaggerated knowing Atta’s identity because he supported using Able Danger’s techniques to fight terrorism. It shows that while Shaffer has consistently asserted that he believes he saw Atta’s photograph, Philpott recanted his initial recollection.”

“If you read that Post story, it makes it seem like Scott lied,” says Mike Kasper, a computer programmer who runs www.abledangerblog.com a website dedicated to the scandal. “But when you study the report, you can see that Capt. Phillpott never denied seeing Atta’s picture.

“In fact,” said former Cong. Weldon, “the IG’s investigators came at Scott and Ellen Pressier more times than detectives would confront a suspect in an episode of Law & Order. They kept trying to get they caught up inconsistent statements, but in the end, Capt. Phillpott said he saw Atta.”

On page 18 of the report, there’s a direct quote from Phillpott, who was up to receive a new naval command at the time of the IG’s investigation. This is what he says after the IG’s investigators have informed him that he’s “changed his story”

It’s also clear that, in attempting to impeach Capt. Phillpott, the IG relied heavily on the word of Dietrich Snell, the 9/11 Commission senior counsel, who found Phillpott’s account of the Able Danger findings “not sufficiently reliable to warrant revision of the [Commission] report or further investigation.” That was Snell’s conclusion following a July 12,2004, meeting with Phillpott ten days before the Commission’s “final report” was to go to press.

It’s also clear that, in attempting to impeach Capt. Phillpott, the IG relied heavily on the word of Dietrich Snell, the 9/11 Commission senior counsel, who found Phillpott’s account of the Able Danger findings “not sufficiently reliable to warrant revision of the [Commission] report or further investigation.” That was Snell’s conclusion following a July 12,2004, meeting with Phillpott ten days before the Commission’s “final report” was to go to press.

We considered Mr. Snell’s negative assessment of Capt. Phillpott’s claims particularly persuasive given Mr. Snell’s knowledge and background in antiterrorist efforts involving al Qaeda. Mr. Snell considered Capt. Phillpott’s recollection with respect to Able Danger’s identification of Mohammed Atta inaccurate because it was ‘one hundred per cent inconsistent with everything we knew about Mohammed Atta and his colleagues at the time.’ Mr. Snell went on to describe his knowledge of Mohammed Atta’s overseas travel and associations before 9/11 noting the “utter absence of any information suggesting any kind of a tie between Atta and anyone located in this country during the first half of the year 2000,’ when Able Danger had allegedly identified him.

But in this book we’ve demonstrated that there was massive evidence on the high visibility of 9/11 hijackers al Midhar and al-Hazmi, who were living openly in San Diego as early as January 2000. We showed how Atta himself entered the U.S. on June 3 and rented a room in Brooklyn near the al Farooq Mosque, using his own name. Just how difficult would it have been for the Able Danger analyststo track his movements via airline reservations and immigration sources, since, according to the IG’s report, the Able Danger data harvest was “collecting data from 10,000 web sites each day?”

In an interview following release of the report, one operative close to the data-mining operation told me that “we also accessed INS databases in the data harvest, so picking up Atta who had to get airline tickets and a visa prior to his arrival in early June was no big deal.”

There’s further evidence to assess the credibility of the IG’s report.

It documents expenditure of upwards of $1 million to fund the Able Danger operation when it moved from LIWA at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, to Garland, Texas, in the summer of 2000. The first appropriation signed off on by SOCOM was for $750,000; then, that fall, General Pete Schoomaker, the chief of SOCOM, was encouraged enough by the hits the team was getting that he approved another quarter million for an additional month. Yet the IG’s report characterizes the data mining operation as little more than “a proof of concept for data mining,” lacking in any significant intelligence results.

Quoting an unnamed colonel, the report concludes that “in terms of . . . identifying al Qaeda and analyzing its vulnerabilities, the team was only ‘30 percent’ successful’ and ‘it was not validated.’” Another official is quoted as saying “We didn’t get the mission accomplished.”

“So what I want to know,” said Weldon in a 2006 interview, “as a lawmaker with some oversight on Pentagon spending . . . if this program was so worthless, why did SOCOM spend a million dollars on it in a matter of a few months?”

Perhaps the most insidious aspect of the DOD Report was its characterization of Lt. Col. Anthony Shaffer as “basically the delivery boy” for DIA on the Able Danger project. Shaffer was also described in the report as “minimally qualified” at HUMINT (human intelligence).

Yet a cursory examination of Shaffer’s service record shows that he spent more than twenty-two years of his army career as a human intelligence officer. His decorations for HUMINT work include the Joint Commendation Medal, the Defense Meritorious Service Medal, and the Bronze Star. From 1993 to 1995 Shaffer was actually the chief of army controlled HUMINT operations—in effect, the army’s top human intelligence officer. In his civilian capacity Shaffer was selected as part of the Exceptional Intelligence Professional Program in 1998 for promotion to GS-14 by Lt. Gen. Patrick Huges, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency. Only ten intelligence operatives out of a pool of ten thousand were selected for this highly competitive program.