1000 YEARS FOR REVENGE: Chapter 30 John Doe No. 2

At 9:00 a.m. on April 19, 1995, a twenty-foot GMC twin-axle model parked outside the America’s Kids Day Care Center at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. Inside was a 5,600-pound device made of ammonium nitrate and nitromethane, a racing fuel. At 9:02:13 a.m. it detonated. In an instant, 168 people, including nineteen children, were dead.

An hour and a half after the blast, on Interstate 35, an Oklahoma highway patrolman stopped a yellow Mercury Marquis that had been driving without a plate. Behind the wheel, carrying a loaded .45 caliber Glock pistol, was Timothy McVeigh, a former army sergeant. He was immediately arrested and locked up in the courthouse in nearby Perry, Oklahoma.

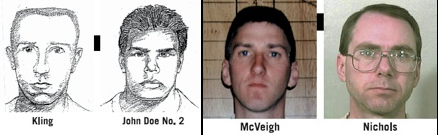

Soon, in a remarkable replay of the WTC investigation, the FBI traced a VIN number on the axle of the Ryder to a rental agency in Junction City, Kansas. There, witnesses gave police a description of two men who rented the truck. An artist’s sketch was prepared. One suspect, who gave his name as Robert Kling, was described as 5’ 10” and 180 pounds, with light hair and a medium build.

The second man, who would become known as “John Doe. No. 2,” was variously described as 5’9” to 5’10”, with a dark complexion, brown hair combed straight, and a tattoo on his left arm. Using the sketch in a door-to-door canvass, police traced “Kling” to a motel in Junction City, where he’d rented a room under his real name: Tim McVeigh. As his place of residence he’d given the address of a farm in Decker, Michigan, that was occupied by James Nichols. When an FBI SWAT team swooped down on the farm, they learned that Nichols’s younger brother Terry lived in Kansas.

The next morning, in a routine phone check, the police discovered that McVeigh was already in custody. When Terry Nichols learned the Feds were after him, he promptly surrendered.

But there was a problem. While the suspect sketch for John Doe. No. 1 was a dead ringer for McVeigh, Nichols was a pale-skinned Anglo with a thin neck and glasses. He looked nothing like the dark, swarthy John Doe No. 2 in the sketch. Furthermore, in the hours immediately after the bombing, an APB had gone out for suspects seen near a brown Chevy pickup. They were described as being of Middle Eastern extraction. Acting on what he’d heard in those early hours, David McCurdy, former U.S. congressman from Oklahoma and chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, announced that the bombing was the work of Middle Eastern terrorists.

The evidence linking Nichols and McVeigh to the bomb was convincing. The pair had first met in 1988 during Army basic training in Georgia. Nichols later served with McVeigh at Fort Riley, Kansas. The previous September, Nichols had bought two thousand pounds of ammonium nitrate fertilizer; two weeks later he bought another ton.

An associate, Michael Fortier, who became a government witness, described how McVeigh had experimented with pipe bombs and other explosives. McVeigh and Nichols had rented storage lockers together where materials were kept.

On April 17, a Ryder truck like the one that carried the bomb was seen behind Nichols’s house in Kansas. The next day, a Ryder truck and a pickup resembling Nichols’s GMC Sierra were seen near a lake where investigators soon found a substance believed to be fuel oil. Investigators later identified this as the point where the delicate mixture of racing fuel and fertilizer was combined.

But the FBI said it was pressing ahead in the hunt for “John Doe No. 2.” In fact, the federal indictment named Nichols, McVeigh, and “others unknown,” suggesting, at that point in early May, that the Feds still believed the two angry ex-Army buddies were involved in a broader conspiracy.

The Bureau then embarked on the biggest manhunt in American history. Ten thousand phone tips were processed, and dozens of John Doe No. 2 lookalikes were interviewed. The suspect was further described by witnesses at McVeigh’s motel as being 5’ 9”, with dark brown hair brushed back and olive skin.

On the morning of the bombing, a witness at a tire store said that McVeigh had stopped to ask directions to the Murrah Building. The man with him was “dark skinned.” Daina Bradley, who lost a leg in the explosion, remembered seeing the yellow Ryder truck pull up minutes before the blast; a man got out, she said, wearing a dark blue jacket and baseball cap. Bradley, who also lost her mother and two children in the bombing, testified that the man was not McVeigh. Nor, apparently, was it Nichols. According to his wife Marife, Terry was home in Herington, Kansas, at the time.

Perhaps the most probative description of John Doe No. 2 came from FBI Special Agent Henry C. Gibbons a twenty-six-year-veteran. In a sworn affidavit, Gibbons reported that on April 19 “a witness near the scene of the explosion saw two individuals running from the area of the Federal Building toward a brown Chevrolet truck. The individuals were described as males, of possible Middle Eastern descent.”

But once Nichols and McVeigh were charged, and federal prosecutors began gearing up for trial, the Justice Department quietly dialed back on the hunt for a third suspect. By 1997 Federal officials were asserting that the original sketch of the dark, olive-skinned man was based on a mistake by a witness. Nichols and McVeigh were eventually convicted and McVeigh executed, insisting to the end that there had been no outside help.

Both Bomb Makers in Cebu

The case for a Mideast connection to the blast is circumstantial but worthy of review, given what we now know about Ramzi Yousef’s capabilities, and about a curious series of events and connections leading up to the blast. None of them, in isolation, is conclusive, but as pieces of the larger “mosaic” they raise questions.

On the morning of April 19, while sitting in his cell in New York federal jail, Abdul Hakim Murad made a startling claim. After listening to a radio report on the OKC bombing, a Bureau of Prisons guard went to Murad’s cell. When the guard asked what Murad thought about the bombing, the prisoner shot back, “That was us.”

“What are you talking about?” asked the startled guard.

“Oklahoma City. The bomb,” said Murad. “We did that.”

The guard eyed him. How could he possibly be connected with a bombing in another state when he was in Federal jail?

Murad had just arrived in New York six days earlier after leaving the Philippines, where he’d been held in detention for more than two months.

But the terrorist asked for a paper and pen. He wrote downsome words and passed the note back to the guard.

It said “We claim credit in the name of the Liberation Army.” If a boast like that had come from just any prisoner, it might have been dismissed out of hand. But the claim of credit was now coming from the oldest friend of the world’s most notorious bomber.

Yousef was down the hall in the ultra-secure Special Housing Unit of the MCC, where. he’d been held since his rendition on February 8. But two other co-conspirators of his Manila cell were still on the loose. Wali Khan Amin Shah had escaped from the PNP at Camp Crame after his arrest on January 12, and Yousef’s uncle, Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, was virtually unknown to the Feds at this point.

Was it possible that Ramzi Yousef could have somehow been tied to this second strike on America? Murad’s claim seemed preposterous, but the FBI wasn’t taking any chances.

The day after the bombing, Special Agent Frank Pellegrino and Secret Service Agent Brian Parr were dispatched to the MCC. They interviewed the guard’s boss, Lieutenant Philip Rojas, who confirmed that Murad had made the statement.

Taking Credit For the Blast

The agents then summarized their findings in an FBI 302. In the trial of Yousef, Murad, and Shah for the Bojinka plot a year later, the Feds would actually point to that 302 as evidence that as late as April 19, 1995, Murad was still involved in a conspiracy.

That fact alone doesn’t necessarily tie Yousef to the Murrah Building bomb, but there’s a pattern of other circumstantial evidence connecting him to the device. All of it relates to McVeigh’s bombing partner, Terry Nichols.

Yousef and Shah applied for their final visas to the Philippines in Singapore on November 3, 1994. The very next day, at the Philippines consulate in Chicago, Nichols got his visa. Trial records and documents from the Philippine National Police show that Nichols was in Cebu City at the very same time as Yousef in December 1994—staying in a section of the Visayas island group that was a hotbed of Islamic fundamentalism.

Nichols had extensive Philippine connections. In 1989, after divorcing his first wife, a Las Vegas real estate broker named Lana Padilla, he married Marife Torres, a nineteen–year–old Filapina from Cebu City. Nichols was a disaffected ne’er-do-well who had railed against the government for years. An out-of-work farmer, he seems to have been virtually destitute from the early 1990s to the moment of his arrest. In 1992 Nichols was sued by Chase Manhattan Bank for $17,860 in unpaid credit card debt. In March 1994, in an effort to avoid paying taxes, he filed an affidavit declaring himself a “non resident alien. That same month he moved Marife to Marion, Kansas, where he answered a help-wanted ad in a farm journal and took a job as a simple ranch hand.

Yet Nichols seemed to have unknown sources of funding. From 1990 to 1994 he made a total of five trips to the Philippines, and lived with Marife for a time in Cebu City, not far from where the Abu Sayyaf terror group was active.

Before departing on his last trip to Cebu on November 22, 1994, Nichols gave ex-wife Padilla a series of letters and instructions to be implemented if he didn’t return within sixty days.

One handwritten note told McVeigh to clean out a pair of storage lockers and “Go for it.” The postscript said, “This letter would be for purposes of my death.” Fearing her ex-husband might be suicidal, Padilla opened her letter immediately. It directed her to a bag hidden in her kitchen containing twenty thousand dollars in cash.

There were keys to a storage locker, which contained a bizarre cache of wigs, ski masks, panty hose, and gold coins, along with gold bars and bullion estimated to be worth sixty thousand dollars. The Feds later claimed that this was the swag from a robbery Nichols had committed in Arkansas, but evidence presented at Nichols’s and McVeigh’s separate trials later challenged that theory.

Whatever the source of the income, the notes Nichols left with Padilla suggested that Nichols believed his last trip to the Philippines would be dangerous. He stayed in Cebu City from late November until January 16, 1995—the same period when Yousef was in Manila planning the plot against the Pope, the Bojinka airline bombings, and the suicide hijackings.

Edwin Angeles’s Affidavit

That might be dismissed as coincidental—except for a sworn affidavit from Edwin Angeles, the former leader of the Abu Sayyaf Group, who later cooperated with the PNP.

During a police interrogation in 1996, Angeles swore that he had met Yousef, Shah, and Murad in Davao City in the southern Philippines as early as 1991. Present at the meeting, he said, was a man named Terry Nichols, who was introduced to Angeles as “a farmer.” Angeles said that they discussed “training on bomb making and handling.”

In a summary of the police report on the interrogation, Angeles identified the site of the meeting as the Del Monte labeling factory in Davao City. He later drew a sketch of the so-called “farmer” that bore a striking resemblance to Nichols.

PNP intelligence documents show that Murad was training at a Philippines flight school from December 1990 to January 1991. Yousef was in the southern Philippines island of Basilan training Abu Sayyaf terrorists in the summer of 1991.

There was other official evidence of a possible Yousef-Nichols connection.

In 1996 Oscar P. Coronel, Chief of the Intelligence Division of the Philippines Bureau of Immigration, issued a report to his commissioner regarding interviews he conducted in reference to Marife Nichols. His handwritten notes in an attachment entitled “Summary Information Sheet” indicate that a “group of aliens of [the] Nichols group” included “Pakistanis, Abu Sayaf [sic], Arab Nationals” and “other middle east terrorist[s].”

Meanwhile, after Nichols left Manila, a phone card used by him and McVeigh in the name of Darryl Bridges showed a total of seventy-eight calls to a guest house in Cebu where Marife had been staying. The guesthouse was owned by her uncle, who had once lived in Saudi Arabia.

It was reportedly frequented by Muslim fundamentalist students from a nearby college. There were twenty-two attempts to get through to the guesthouse on February 14 alone. Was Nichols simply desperate to connect with Marife’s family, or was he calling for follow-up advice on how to build an ammonium nitrate-nitromethane bomb?

The Yousef-Nichols Connection

Yousef had fled Manila by the time Nichols left in mid–January 1995, and there’s no hard evidence that the two ever met in December 1994. The only time that Yousef was known for certain to be in Cebu during this period was for a few hours as he fled back to Manila following his “wet test” on the PAL flight December 11. But the log book of the Dona Josefa apartments show visits to Room 603 by a man named “Nick” while Yousef was in residence.

It’s impossible to say whether that “Nick” was Terry Nichols, but the idea that two men connected to the two most notorious bombings on U.S. soil would be in the same remote town in the Philippines seems more than coincidental, especially considering that each of them was connected to a fertilizer-fuel device of enormous destructive power, delivered to its target in a yellow Ryder truck.

At McVeigh’s trial, his lawyer Stephen Jones tried to introduce evidence of “others unknown,” referencing a Philippine connection to the bombing, but the evidence was excluded. Jones had developed information that as early as August 1990 Nichols had asked a Philippines tour guide named Daisy Legaspi if she “knew someone who knows how to make bombs.” Further, a number of calls on the Darryl Bridges card had been to Starglad Lumber in Cebu. The manager of Starglad was one Serafin Uy, whose brother was slain after being suspected in a series of kidnappings in Mindanao.

When a U.S. consulate representative interviewed Uy, he said that Marife Nichols’s father—a former policeman he knew—had found a book on the making of explosives in Nichols’s personal effects left in Cebu. Jones was convinced that Nichols had gone to Cebu on that last trip to study bomb making from the master himself: Ramzi Yousef.

“Tim couldn’t blow up a rock,” Jones told Insight Magazine. But right after that trip Nichols and McVeigh reportedly began building a device of enormous destructive power—despite the fact that they were relatively inexperienced as bomb makers. That point was underscored at trial by Michael Fortier, the government’s star witness.

He testified that while the pair experimented with small pipe and bottle bombs, McVeigh’s one attempt at exploding an ammonium nitrate-fuel oil device in a milk jug, “didn’t work.”

“The one time that we know of when McVeigh experiments with an ANFO bomb it’s a dud,” Oklahoma attorney Mike Johnston said in an interview for this book. “Then Nichols goes to the Philippines while Ramzi is there, and after that these guys build an even more sophisticated ammonium nitrate-nitromethane device that takes down the Federal Building. What are the odds?”

Also interviewed for the book, Jones said that his own explosives experts, hired for McVeigh’s defense, doubted whether he or Nichols had the expertise to build the Murrah Building device. McVeigh made a crude sketch of the bomb for the experts, but when pressed on where he got the knowledge to build such a complicated device, McVeigh came up with a vague story.

“He said, ‘Well I found this book at the Kingman Library,’” said Jones, recalling McVeigh’s explanation. “And I said, ‘You found a book in the Kingman, Arizona, Public Library that tells you how to build a bomb that will blow up a building and kill a hundred and sixty eight people?’ And he said, ‘Yes.’”

Jones said he asked McVeigh for the book’s title, but the self-confessed bomb-builder couldn’t remember. So Jones’s investigators searched the Kingman Library.

“Of course, they couldn’t find anything like it,” he said.

McVeigh insisted to the end that he and Nichols had acted alone But his own lawyer remains unconvinced.

“There simply is no evidence,” said Jones, “that Terry Nichols or Tim McVeigh or anybody known to have been associated with them had the expertise, knowledge, skill [and] patience to construct an improvised device that would bring down a modern nine-story office building.”

In the absence of any other explanation, Jones believes today that Nichols and McVeigh got their bomb-building knowledge from Ramzi Yousef.

“The Philippines connection is the most credible, most consistent and frankly most complete explanation of how they built the bomb,” he said. “It’s not perfectly complete but there’s no other explanation. There’s nobody else that’s been identified. No other organization that’s been identified. There simply is a lack of evidence of anybody else.”

Attorney Mike Johnston agrees, but he believes Yousef had a different paymaster than Osama bin Laden. On March 14, 2002, he filed suit in U.S. District Court against the Republic of Iraq. Suggesting that Yousef was an Iraqi agent, the complaint alleged “dramatic similarities” between the 1993 Trade Center bomb and the Oklahoma City device.

In a motion for Summary Judgment filed March 3, 2003, Johnston added a tantalizing new piece of evidence to his theory that Yousef designed the bomb for Nichols and McVeigh. He claimed that a cell phone rented in Manila for Abdul Hakim Murad “showed continued usage until March 1995”—that is, after Murad’s arrest, suggesting that someone else involved with the Yousef cell was using it.

Four calls on the phone were made from the Philippines to area code 918, which is in eastern Oklahoma. According to Johnston, the Daryl Bridges phone card used by Nichols and McVeigh showed calls to Starglad Lumber in Cebu “during this exact time.”

“You had the most notorious bomb building terrorist on earth in the same Philippines city as one of the Oklahoma City conspirators,” said Johnston. “Both Nichols and McVeigh were lightweights when it came to explosives. Terry goes to Cebu and when he comes back he helps build a device with the same kind of design and explosive power as the Trade Center bomb. That’s a fact pattern that simply defies probability.”

O.K. City Bomb Threatens Day of Terror Mistrial

Is it conceivable that Ramzi Yousef, in the midst of planning three ambitious acts of terror, found the time to teach Terry Nichols how to build a weapon of mass destruction?

Yousef was clearly a teacher. Testimony in the Bojinka case would show that he made diagrams of his Casio-nitroglycerine bomb for both Murad and Wali Khan Amin Shah. He’d given bomb-making lessons to the Abu Sayyaf Group, and had planned to visit Egypt, France, and Algeria to teach al Qaeda terror cells how to build his undetectable bomb.

The Oklahoma City device reportedly bore similarities to both the UNFO bomb Yousef used at the Trade Center and the ANFO bomb he was suspected of designing to destroy the Israeli Embassy in Bangkok.

But Yousef’s own attorney scoffs at any hint of an Oklahoma City bombing tie.

“The allegations of a connection between my client and the Murrah Building bomb are completely specious,” said Bernie Kleinman, who has represented Yousef since after the Bojinka trial. “It was Stephen Jones’s ridiculous attempt to find some other basis for representing his client. There’s zero in that. There were a lot of guys in the Philippines looking for wives, and Nichols happened to be there when Yousef was there. I also thought it was funny that the one purported witness [Edwin Angeles] turned out to be an incredibly good sketch artist. What a coincidence. It was like the people who see UFOs.” Nevertheless, Kleinman said he suspects Nichols and McVeigh may have had outside help—from right-wing militia groups.

At one point after sentencing, McVeigh was actually on the same cellblock as Yousef in the Supermax prison. Incredibly, the two convicted bombers were able to converse. A source close to Yousef in the prison said that the bomb maker had expressed the opinion that McVeigh was incapable of building the OKC device on his own.

As to Yousef’s connection to Nichols, Kleinman said he asked his client about the issue only once. “He didn’t say ‘No,’ said Kleinman. “But there was an expression on his face like ‘What a stupid thing to say.’”

Still, conspiracy Web sites and journalists on the political right and left alike have continued to support the theory, and in October 2002 it was given further credence by an article and editorial in the Wall Street Journal.

Whether Yousef was involved or not, the timing of the OKC bombing threatened to cause a mistrial in the case against his supporter in the Trade Center bombing, Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman. The day after the Murrah Building devastation, lawyers for the defendants in the Day of Terror case alleged that the graphic news from Oklahoma City prevented their clients from getting a fair trial. Their motion came three months into the epic proceeding, after 7,500 pages of testimony had been heard. A mistrial at that point would have been incredibly costly for the government, and in the absence of any hard evidence that the jury had been prejudiced by the OKC publicity, Judge Mukasey denied the motion. Also, just as he’d done earlier in the days following Yousef’s arrest, he refused defense requests to sequester the jury.

Recent Comments