Recent Posts

- Get HOMICIDE in four editions. Rated No.1 among The Five Best Crimes Biographies of All Time

- HOMICIDE AT ROUGH POINT, the true crime story launched in Vanity Fair on how billionairess Doris Duke killed designer Eduardo Tirella outside the gates of her Newport, RI estate and got away with murder

- Peter Lance Biography

- HuffPost: DOJ report on MISSBURN case leaves out key detail: I.D. of the Mafia killer who broke the case for Hoover’s FBI

- With President Trump’s order to release files on JFK’s death, consider my 1983 ABC NEWS report on public concerns back then that The Feds were hiding the truth

Archives

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- November 2023

- June 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- September 2017

- June 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- June 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- March 2010

- August 2009

- November 2006

- November 2004

- October 2003

- September 2003

- February 2000

Categories

- 1000 Years for Revenge

- ABC's Path to 9/11 issue

- Ali Mohamed

- Ali Mohamed revelations

- Anwar al-Awlaki

- ARCHIVES

- awards

- bio

- BIOGRAPHY

- BOOK TV C-SPAN2

- BOOK WRITING

- BOOKS

- Colombo family "war"

- Commentary

- DUI investigation

- Emad Salem investigation

- FBI ORGANIZED CRIME

- Featured

- FICTION

- First Degree Burn

- Fitzgerald censorship attempt

- Fitzgerald censorship scandal

- Fox News

- Gotham City Insider

- Gregory Scarpa Jr.

- Gregory Scarpa Jr.

- Gregory Scarpa Sr.

- Harpercollins

- HUFFINGTON POST

- INVESTIGATIONS

- Khalid Shaikh Mohammed

- MAGAZINE ARTICLES

- Major Hasan Fort Hood massacre

- MEDIA COVERAGE

- Meier Kahane Assassination

- Meir Kahane assassination

- Murder Inc.

- Nat Geo whitewash

- NEWSPAPER REPORTING

- NOVELS

- Oklahoma City bombing

- Omar Abdel Rahman

- OPERATION ABLE DANGER

- POLICE CORRUPTION

- Produced

- R. Lindley DeVecchio

- Ramzi Yousef

- Ramzi Yousef sting 302's

- REPORTING & ANALYSIS

- RESEARCH

- Santa Barbara News-Press

- SCREENWRITING

- Stranger 456

- Stranger 456

- teleplays

- Tenacity Media

- Triple Cross

- Triple Cross

- TV NEWS COMMENTARY

- Uncategorized

- videos

- WIKIPEDIA

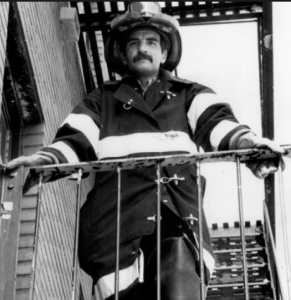

Never forget hero FDNY Fire Marshal Ronnie Bucca who gave his life 23 years ago on 9/11

By Peter Lance 9.11.24 On the 23rd anniversary of the worst intelligence failure since The Trojan Horse, please remember this extraordinary Fire Marshal who gave his life on 9/11. I first met Ronnie Bucca, an ex-Green Beret and veteran of the FDNY’s elite Rescue One Company, 26 years ago when I was introduced to him by Louis F. Garcia, who later became the Chief Fire Marshal in Manhattan.

By Peter Lance 9.11.24 On the 23rd anniversary of the worst intelligence failure since The Trojan Horse, please remember this extraordinary Fire Marshal who gave his life on 9/11. I first met Ronnie Bucca, an ex-Green Beret and veteran of the FDNY’s elite Rescue One Company, 26 years ago when I was introduced to him by Louis F. Garcia, who later became the Chief Fire Marshal in Manhattan.

At that time in 1997 I gave Ronnie a copy of my first novel, “First Degree Burn,” The hero of that thriller was a Fire Marshal for the FDNY, so I signed it “This is fiction, you’re the real thing.”

Little did I know how true those words were because 22 years ago today, after AA Flight 11 struck the North Tower of the WTC Ronnie roared down “lights & sirens” to Liberty Street with his boss, Fire Marshal Jimmy Devery.

They parked outside of Ten Engine & Ten Truck, donned their turnout coats and made their way up the back stairs of the South Tower after UA 175 had struck.

Against overwhelming odds Ronnie actually made it to the “fire floor” on 78 — reaching higher than any other FDNY member in either Tower that day except one: Battalion Chief Oreo Palmer.

As the flames roared around them, these two men did their best to protect the injured when the Tower collapsed and they died with their boots on — two of the more than 400 first responders who gave their lives that day.

Fire Marshal Devery, who had rescued a badly burned woman named Ling Young on the 51st floor got her to safety and survived.

THE PAUL REVERE OF THE “WAR ON TERROR”

Years before that Ronnie Bucca had predicted that the al Qaeda cell responsible for the first attack on the WTC (the 1993 bombing) would return to New York someday to finish the job.

Though many who encountered him thought he was delusional, the security clearance he had in an Army Reserve intelligence unit tasked to DIAC: the Defense Intelligence Analysis Center at Bolling AFB in D.C., gave him access to Top Secret intel.

Though many who encountered him thought he was delusional, the security clearance he had in an Army Reserve intelligence unit tasked to DIAC: the Defense Intelligence Analysis Center at Bolling AFB in D.C., gave him access to Top Secret intel.

What Ronnie saw demonstrated that for years the FBI had failed to connect “dots” of evidence in their own files pointing to Ramzi Yousef, the mastermind of the ’93 bombing and his obsession with taking down The Towers.

One night, at “Suspenders,” an FDNY watering hole at 2nd Avenue and 38th St., now called “Bravest,” Ronnie corralled FM Garcia and another Fire Marshal, Jimmy Kelty and said, “They’re coming back.”

Kelty shook his head. He’d heard this from Ronnie before. In fact, his brother Gene was a captain at 10 Ladder and 10 Engine on Liberty Street, the firehouse dedicated to protecting the WTC. Nobody wanted to see the Towers hit, said Jimmy. But they’d been locked down for years.

“Janet fuckin’ Reno couldn’t get into that underground garage,” he said.

Garcia agreed. It seemed like a long shot. But Ronnie knew the history.

“Call it payback for an old score,” said Bucca.

“I don’t follow,” said Kelty.

Ronnie pointed to the Maltese cross on the navy blue Ten and Ten T-shirt Jimmy was wearing; a gift from Gene.

“You know where that came from?”

“Knights of Malta? The Crusades, right?” said Garcia.

“Yeah,” said Ronnie. “The eleventh century. When the knights came down from Europe and hit the castles of the Saracens, they poured burning naphtha down on them. So the knights organized the first fire brigades. We’ve worn that cross ever since.”

Kelty eyed him. “Sooooo. You’re saying this thing with the Arabs started when?”

“A thousand years ago,” said Ronnie. He walked over to the window, looked out on Second, and pointed downtown toward the Trade Center. “We took their castles, and now they’re gonna come back and take ours.”

And on 9/11 they did — in a plot executed by Ramzi Yousef’s uncle Khalid Shaikh Mohammed.

Later, the first POW camp in Iraq was named for Ronnie who is as beloved in The Special Forces as he is in The Fire Service.

Because I’d met him so many years before, his widow Eve gave me permission to tell his story in what became my first of four investigative books for HarperCollins: “1000 Years For Revenge International Terrorism and The FBI: The Untold Story.”

Lou Garcia went on to distinguish himself as the Chief Fire Marshal for The City of New York and the Bucca family included my book in a memorial exhibit in Ronnie’s memory at Fort Totten in Queens, inside a building that was once the headquarters of The Army Corps of Engineers.

Eight years ago, “1000 Years” was cited in a piece by Mark Lungariello in The Journal News, a newspaper near the town of Tuckahoe, New York where the hero fire marshal lived with his wife Eve and children Ronnie Jr. and Jessica.

This excerpt from the book recounts how Ronnie miraculously survived a life-threatening injury during a rescue attempt in 1986 only to make his way in one year back to Rescue One, the “Green Berets of the FDNY.” It will help to redefine the word “hero” for you.

Whatever your faith is, say a prayer for Ronnie, the other fallen 400 and the many Members of Service who worked “the pile” and have never recovered, physically or mentally.

THE FLYING FIREFIGHTER

Just after noon on September 16, 1986, Ronnie Bucca was working as an outside vent man on the day tour at Rescue One, the busiest heavy rescue company in New York City. Ronnie, his lieutenant, and four other firefighters had just knocked down an electrical fire in the West 20s and were “taking up,” returning to the house on West 43rd Street, when they got the call from Dispatch. A 10-75, the FDNY code calling for backup assistance from a rescue company, had been transmitted for Box 22-1138 at 483 Amsterdam Avenue on the Upper West Side. 40 Engine and 35 Truck had responded. Dispatch indicated that the “fire ground” was on the fourth floor, moving toward “exposure two,” the right side of the building.

In the cab of the company’s big Mack R truck, Lt. Steve Casani, a blue-eyed Irish-Italian bear, turned to his driver (known as the chauffeur) and said, “Hit it.”

In the cab of the company’s big Mack R truck, Lt. Steve Casani, a blue-eyed Irish-Italian bear, turned to his driver (known as the chauffeur) and said, “Hit it.”

The siren roared and the enormous “toolbox on wheels” headed up Eighth Avenue to the Upper West Side. Heavy rescue companies like “One” were created to provide backup for working fire suppression units. Their job was to get inside, help move the hose, help vent the flames, and look for bodies, both civilians and Members of Service (other firefighters).

“By the time we got there,” recalled Casani, “The fourth floor was engulfed. 40 Engine needed help, so we went to work.”

Hydrants were tapped, hose lines were pulled, and 35 Truck’s ladder rose toward the roof of the five-story old-law tenement. As the men from Rescue One jumped off the truck, they quickly pulled their Scott Air Packs over their Nomex turnout coats.

Ronnie Bucca, a darkly handsome ex-Green Beret Reservist who’d made dozens of jumps with the 101st Airborne, was known for his attention to the gear. He took an extra second to buckle his harness so that the thirty-five-pound compressed air bottle on his back would stay secure.

It was a move that would soon save his life.

Ronnie grabbed a Haligan forcible entry tool and took off with firefighter Tommy Reichel into 485 Amsterdam, the tenement next to the fire building. A five-mile-a-day runner, Bucca took the steps two at a time. At 5’9” and 165 pounds Bucca was slightly built compared to some of the “beefalos” in the house, but what he lacked in size he made up for in tenacity and heart.

At the roof, Ronnie burst through the door and was immediately pushed back by the heat. Even under his mask he felt it. Next door, the fourth floor at 483 Amsterdam was an inferno. Just then, over the Handie-Talkie radio clipped to his turnout coat, he heard a Mayday from Lt. Dave Fenton from 35 Truck, who was trapped on the 5th floor. There was a fire escape outside, but in a classic New York irony, the windows were covered by security “scissor gates.” Designed to keep predators out, the gates had locked the lieutenant in, and he was running out of time.

Ronnie climbed through a gooseneck ladder onto the fire escape. As soon as he hit the rusted metal he slipped. The broken glass on the grid was like ice. Worse, smoke thick as pea soup was coming out of the windows behind the gates. Ronnie tightened his mask and switched on the Scott’s bottle. Compressed air filled his lungs. He moved cautiously to the edge of the fire escape and leaned over to smash the glass.

The smoke rushed out. Ronnie leaned over again and made a stab with the Haligan tool, trying to hook the gates and pop them free. But as he swung out, he slipped on the glass and went over the edge, going down past the fourth floor, then the third, falling face up as he dropped.

Miraculously, at the second floor level, the Scott’s Air Pack he’d so tightly cinched hit a metal conduit –a two-inch pipe across the alley that delivered electricity to the building. The force of the impact flipped Bucca 180 degrees and partially broke his fall.

He landed hard in a pile of debris on the ground level. The last thing he remembered was hearing a cracking sound. At that moment, Lt. Fenton broke free. He moved to a fifth floor window, which he smashed to help vent and get air. But when he looked down, Fenton saw Ronnie’s body lying in the alley. His boots were twisted outward as if his legs had snapped. Bucca wasn’t moving.

“Jesus,” Fenton thought as he clicked on the Handie-Talkie.

“Mayday. Mayday. Man down in the alley.” He didn’t wait for a response. Fenton took off down the stairs.

Now, as he fought the blaze with firefighter Tom Reilly on the fourth floor, Lt. Steve Casani heard the distress call. The two of them rushed to the window and looked down.

“Christ,” said Casani. “I just lost my first guy.”

Fenton was first to hit the alley. When he saw Ronnie he was sure he was dead. But he leaned down, felt Bucca’s neck, and got a pulse. There was respiration, but maybe not for long. Fenton quickly pulled off his own turnout coat and covered Ronnie as Casani and Reilly burst into the alley from upstairs.

Right away, Casani jumped on the radio. “I need a Stokes basket and a bus,” he said, using FDNY speak for a rescue stretcher and an ambulance. Roosevelt Hospital was closest, but Casani demanded they head to Bellevue, which had a trauma unit. The only problem was, Bellevue was fifty blocks south and clear across town. Reilly didn’t think he heard right.

“Lieu, East 31st? At noon on a Tuesday? We’re on the fuckin’ West Side.”

“Then call the fuckin’ P.D.” growled Casani. “Have ‘em clear Fifth.” He looked down at Ronnie. “I am not gonna lose this kid.”

Minutes later the siren roared. Casani was in the back of an FDNY rescue unit gripping Ronnie’s hand as the ambulance cut through Central Park and did sixty behind Rescue One’s Mack R, cutting a swath through the noon traffic down Fifth Avenue. As the chauffeur looked left and right, virtually every intersection had been blocked off by an NYPD sector car, an FDNY ambulance, or a piece of fire apparatus. It was perhaps the greatest single midday hospital run in FDNY history, and soon the radio stations got word.

The anchor on WINS Radio said that traffic was being blocked on Fifth Avenue between 96th and 34th streets. Mayor Koch and Cardinal O’Connor were on their way to Bellevue. A firefighter had been badly injured after a five-story fall; his name was being withheld pending notification of next of kin.

Ronnie’s brother Robert, a former medic with the 82nd Airborne who was then a cadet at the Police Academy, got the first call. He asked the FDNY to patch him through to Ronnie’s wife, Eve, who was in the kitchen of their modest home north of the city. Eve’s father, Bart Mitchell, had been an FDNY Battalion Chief with the 12th in Harlem.

Her grandfather was a retired FDNY lieutenant who’d worked the Bronx. Growing up, she’d heard the phone ring dozens of times before, but never for something like this. Robert told her not to worry. He’d pick her up in an NYPD sector car for the trip downtown.

When they roared up to Bellevue with siren and lights flashing, there was a small crowd of reporters outside keeping the deathwatch. Ronnie’s older brother Alfred, who worked for the Transit Authority, was outside along with Ronnie’s parents, Joe and Astrid, and a few of his buddies from the 11th Special Forces. Together they moved past the press gauntlet.

In the hallway outside ICU, Eve could feel her heart pounding until the door opened and Lt. Casani walked out, still in his bunker coat. She hesitated, studying his face. Then he grinned. “It’s gonna be all right.” He opened his coat and hugged her.

“At that moment I knew we had a miracle,” said Eve, thinking back. She moved quickly inside toward Ronnie’s bedside and saw that though he was lying flat, barely moving, he was conscious. She bent down and kissed him. Ronnie lifted a finger and Eve squeezed it. He motioned for her to come close and whispered, “Wasn’t my time, Hon.”

Eve bit down on her lower lip, holding back tears. Just then, a young female resident came up behind her. Dr. Lori Greenwald-Stein was holding a set of X-rays. She motioned Eve aside and put the X-rays up on a light box. Ronnie had sustained multiple contusions and lacerations. He’d broken his knee and the first lumbar vertebrae in his back. It was a compression fracture; otherwise Ronnie would have been paralyzed.

Eve closed her eyes.

“Lucky to be alive,” said the doctor. Then she leaned in and whispered, “But if he walks, it’ll probably be with a cane.”

Grateful as she was, Eve rocked back at the news. Her husband had been a firefighter for nine years, and was planning to go the distance. Her father had done thirty-five, and so had his father before him. “Ronnie was always first into the burning building,” said Eve. “As a paratrooper he was the first one out of the plane. The idea that at the age of thirty-two he might spend the rest of his life as a cripple, didn’t even occur to him.”

Later, when some of the family members had left, Eve moved close to Ronnie’s bed. Eyeing the monitors measuring his vitals, she tried to cope by using her Irish. “Hmmm,” she said. “Pretty cheesy way to get out of the house painting.”

Ronnie tried to smile, but his face ached. He gestured her closer. Eve bent down next to him and he whispered, “I’m goin’ back.”

“You mean Rescue?”

Ronnie nodded. Eve was stunned. As well as she knew her husband—how he’d made it out of the Queens projects to qualify for the Green Berets; how he’d earned a position in an elite Screaming Eagles air assault unit; how he’d been cited for bravery by the FDNY—she couldn’t quite believe what she was hearing. Rescue One was the Special Forces of the FDNY.

They went on seven to nine hundred runs a year. The idea of qualifying back into that house after suffering such trauma was unthinkable. Besides, after a life-threatening injury that was sure to leave him at least partially disabled, Ronnie could retire with a three-quarter tax-free pension. A thousand other men would have opted out. Now, looking down at him in the half-body cast, Eve was apprehensive.

“What about light duty?”

“No,” said Ronnie. “It’s Rescue.”

And a year later, almost to the day, Ronnie Bucca was rappelling down a wall at The Rock, the FDNY’s Fire Academy on Randall’s Island. After months of rehab—he began walking slowly, with a cane, then graduated to a treadmill and moved on to weight training—Ronnie Bucca had shed his body brace and completed the “rope course.” It was the last phase of re-training, allowing him to qualify back into Rescue One.

He had finished each of the course evolutions: moving the hose, working the ladder, proving he could lower himself on a rope down the side of a building or lower an injured victim. Even the Mask Confinement Course, where he had to wear a Scott’s mask with its face plate blackened and get through a complicated maze with a limited amount of air in the bottle. This was the one phase of rescue training where most firefighters washed out. But Ronnie did it under the clock, with seconds to spare.

“It’s difficult to emphasize what an achievement this was for him,” said Paul Hashagen, a big 6’5” Rescue One chauffeur who had gone through Probie School with Ronnie. “You’ve got eleven thousand men in the department. A few hundred of the most competitive guys make it into Special Operations Command (SOC) which comprises the Squads and a Rescue company in each of the five boroughs. But everybody wants Manhattan, and there are only twenty-five spots in Rescue One. To re-qualify back into that house after a five-story drop where you broke your back— I’ve got to tell you, that’s astonishing.”

But Ronnie Bucca was half Sicilian and half Swedish on his mother’s side. Eve always said he got his stubbornness from both of them.

Now, as he rappelled down to the bottom of the wall, a half dozen of his “brothers” surrounded him and let out a war whoop.

One of them pasted a joke shipping label on the back of his helmet. It said, “This side up,” but the arrow was pointing down.

The men cheered and lifted him up on their shoulders. Ronnie Bucca, henceforth known throughout the FDNY as “the flying firefighter,” was back.

Months later, Ronnie raced into a burning “taxpayer,” a one-story corner building down on Avenue D in Alphabet City. It was a three-alarm response. Heavy flames licked out of the first floor windows of an abandoned paint store where squatters had come to live in the frigid cold. The old paint cans left in the store were giving off a lethal combination of volatiles, creating a toxic cloud so black that Bucca couldn’t see his hand in front of him. He clipped a Nomex search rope with a carabiner onto a metal door jamb so he could find his way out.

He donned his mask and gave himself air from the Scott’s pack, feeling his way on his hands and knees. It was the Mask Confinement Course all over again, only this time he was crawling past thousand-degree flames. As he inched his way into the store, Ronnie heard a faint whimper. The sound of a little girl.

Feeling his way along some old shelves, he found a door to a back room. Ronnie reached up and tried the knob but it was locked, so he used a modified Haligan tool to pop it open. Searing heat came out as he crawled inside. He could hear the little girl moaning. Ronnie pushed forward and shined his light.

There, huddled inside an old storage cabinet, he saw her two little eyes. She couldn’t have been more than eight, the same age as his daughter Jessica. She was dressed in a urine-soaked oversized Knicks T-shirt. The little girl was half-dead. So Ronnie reached into the cabinet and grabbed her. She was gagging, coughing.

He took off the Scott’s mask and put it around her face, giving her air. The child’s respiration was starting to slow, so Ronnie quickly doubled back along the search rope until he could feel the chill from the outside air.

He was barely out the door when a woman screamed and rushed over. It was the girl’s grandmother. She threw her arms around Ronnie and hugged him for dear life as he passed the child into the hands of an EMS medic. Ronnie dropped down on the curb. The pain in his back was throbbing, but he’d refused to take any medication beyond aspirin; he didn’t want to let on to Lt. Casani or the other men how much the broken back still dogged him. He was about to get up and go back inside when the lieutenant came over and motioned for him to stay down. “They’re all out,” he said, and Ronnie nodded.

He unclipped the buckle on the strap of the Scott’s harness—the one that had saved his life. As he watched the old lady jump into the ambulance with the little girl who was alive because of him, Ronnie knew that all the retraining and the rehab had been worth it.

Later, half a world away in a terror camp near the Afghan-Pakistani border, a fierce young jihadi would begin another kind of training. Ronnie Bucca had dedicated his life to putting fires out. Soon, it would be Ramzi Ahmed Yousef’s mission to start them.

CLICK HERE: for Ronnie’s Wikipedia entry:

CLICK HERE: Internet Writing Journal interview: how Ronnie tried to stop al Qaeda’s attack on The Twin Towers

CLICK HERE for my Huffington Post: “Al Qaeda and The Mob: How the FBI Blew It on 9/11.”

Recent Comments