First Blood: Meir Kahane’s murder. Al Qaeda’s 1st U.S. attack.

By Peter Lance. Tablet Magazine. In the fall of 2009 I received a cryptic email from Emad Salem, the ex-Egyptian Army major who was the FBI’s first undercover asset in what would become known as the war on terror. I’d told Salem’s remarkable story in my last three books, which were critical of the bureau’s counterterrorism record. Because I had treated him fairly, Salem reached out to me after years in the Federal Witness Protection Program.

By Peter Lance. Tablet Magazine. In the fall of 2009 I received a cryptic email from Emad Salem, the ex-Egyptian Army major who was the FBI’s first undercover asset in what would become known as the war on terror. I’d told Salem’s remarkable story in my last three books, which were critical of the bureau’s counterterrorism record. Because I had treated him fairly, Salem reached out to me after years in the Federal Witness Protection Program.

We made plans to meet in early November, after a lecture I was giving at New York University. But Salem didn’t show. I went back to my hotel that night and had chalked it up as a lost opportunity. The phone rang at 2 in the morning. It was Salem, summoning me to a meeting outside 26 Federal Plaza, the building that houses the FBI’s New York office. Very cloak and dagger, but that’s how this man rolls. You don’t infiltrate the cell responsible for the 1993 World Trade Center bombing without practicing a little tradecraft. Anyway, when my cab pulled in to Foley Square a few minutes later, Salem was standing in the shadows.

That was the start of a series of interviews that led to some astonishing revelations about two of the most infamous al-Qaida murders since Osama Bin Laden formed his terror network. The first one—in fact, arguably the first blood spilled by al-Qaida on U.S. soil—occurred on the night of November 5, 1990, just after Rabbi Meir Kahane, the founder of the ultra-nationalist Jewish Defense League, finished a speech at the Marriott East Side in New York.

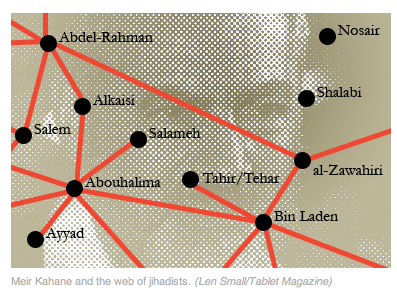

Kahane, a volatile figure who had been expelled from the Israeli Knesset in the mid-1980s and returned to the United States to warn American Jews about what he believed to be a “second holocaust” at the hands of radical Islam, was gunned down by El Sayyid Nosair, an Egyptian émigré. The New York Police Department initially labeled him a lone gunman. I have argued that it was much more than that: an unsolved murder with dire implications for the war on terror.

Now, as a result of new intelligence I’ve learned from Salem, it’s clear for the first time that the rabbi’s death was directly linked to Osama Bin Laden. More surprising, there was a second gunman on the night of Kahane’s murder: a young Jordanian cab driver named Bilal Alkaisi. Alkaisi was also identified in FBI files I’ve obtained as the “emir” of a hit team in a second grisly al-Qaida-related homicide months after the assassination—the 1991 murder of Egyptian immigrant Mustafa Shalabi. The identities of the alleged killers in that second slaying have now become known as a result of information from Salem that prompted the New York Police Department to reopen the Shalabi case.

But the real news is that Alkaisi, originally indicted in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, was cut loose by the feds in 1994 and presumably remains at large. This new intelligence, about a pair of historic terror-related homicides in New York City, lay buried for years in the files of the Joint Terrorism Task Force—until I obtained them from a government source.

As I tell it in “The Spy Who Came in for the Heat,” an investigative piece I wrote for Playboy’s September issue, Emad Salem was arguably the most important asset in the U.S. war with al-Qaida. But my interviews with him and the intel they have kicked loose provide shocking new insights into the ongoing failure of the FBI to reform its counterterrorism capabilities almost a decade after the Sept. 11 attacks.

In order to fully appreciate the significance of these two murders in the history of the war on terror, we need to go back to the summer of 1989, when George Bush was in the White House and terrorism was considered a backwater assignment at the FBI.

The First Shots Fired in Bin Laden’s War Against America

The story begins a year and half before El Sayyid Nosair, wearing a yarmulke, walked into the Morgan D Room at the New York Marriott and killed Kahane.

On four successive weekends in July 1989 (according to trial testimony), agents from the FBI’s Special Operations Group followed a group of “ME’s”—FBI-speak for “Middle Eastern Men”—from the al Farooq Mosque on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn to the Calverton shooting range, a large outdoor sand pit located at the end of Long Island.

Firing a series of weapons, including AK-47s and hand guns, the “ME’s” at the Calverton range included Nosair, then a 34-year-old janitor from Port Said, Egypt, who reportedly popped Prozac and worked in the basement of the Civil Courthouse on Centre Street in Manhattan; Mahmoud Abouhalima, aka “The Red,” a 6-foot-2-inch Egyptian cab and limo driver; Mohammed Salameh, a diminutive Palestinian; and Nidal Ayyad, a Kuwaiti who had graduated from Rutgers University. According to interviews with former FBI agent Jack Cloonan, each of them had been instructed by Ali Aboelseoud Mohamed, an ex-Egyptian Army commando from the unit that assassinated Anwar Sadat in 1981.

Mohamed was the focus of my last book, Triple Cross. In the early 1980s, shortly after being purged by the Egyptian Army for his radical views, Mohamed came under the influence of Ayman al-Zawahiri, the Cairo surgeon who had been jailed for a time for the Sadat murder and went on to form the Egyptian Islamic Jihad. By the end of the decade, after al-Zawahiri met Osama Bin Laden in Afghanistan and merged his Egyptian Islamic Jihad group into what would become al-Qaida, Ali Mohamed became the terror network’s principal espionage agent.

In 1984, Mohamed succeeded in infiltrating the CIA briefly in Hamburg, Germany, got past a watch list to enter the United States a year later, enlisted in the U.S. Army and, astonishingly, managed to get posted to the JFK Special Warfare Center at Fort Bragg, where elite Green Beret officers study. From there, he traveled to New York City on weekends to train the Calverton shooters.

Mohamed was so trusted by Bin Laden that he moved the Saudi billionaire’s entire entourage from Afghanistan to Sudan in 1991, set up al-Qaida’s training camps there, and trained Bin Laden’s personal body guards. He was also one of the principal planners in the simultaneous truck bomb attacks on the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998 that killed at least 223 and injured thousands.

Three of Mohamed’s Calverton trainees were convicted in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing plot. Nosair was convicted in the Kahane killing. A U.S.-born Muslim named Clement Hampton-El was convicted with Nosair in the 1993 “Day of Terror” plot to blow up the Lincoln and Holland tunnels, the George Washington Bridge, the United Nations, and 26 Federal Plaza, the building that houses the FBI’s New York office.

At the time of the Calverton surveillance, the FBI’s Special Operations Group clearly knew that these men were terrorists in training. New York Police Det. Tommy Corrigan, a former senior member of the NYPD-FBI Joint Terrorism Task Force, told me in an interview for Triple Cross that the surveillance stemmed from a tip that PLO terrorists were threatening to blow up casinos in Atlantic City. But for unknown reasons the FBI shut down the surveillance. By the end of that summer of 1989, the “ME’s” and their Green Beret-linked leader faded back into the shadows.

***

In July 1990, following a path similar to Ali Mohamed’s, Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman, the spiritual “emir” of al-Qaida who became known as “the blind sheikh,” got a visa, slipped past the same State Department watch list, and landed at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York. He was met at the airport by Mustafa Shalabi, a big, burly 30-year-old electrical contractor from Egypt who ran the Alkifah Center at the al Farooq Mosque in Brooklyn.

The Alkifah was the principal U.S. office for the Makhtab al-Kidimat, often referred to as the MAK, a worldwide center of storefronts through which millions of dollars in cash was collected to support the Afghan Mujahadeen war against the Soviets, as Steven Emerson documents in American Jihad. By 1989, a year before Abdel-Rahman arrived in New York, Bin Laden and al-Zawahiri had merged their new terror network with the MAK. Its leader, Abdullah Azzam, had been killed in a car bomb in Pakistan in November of that year. Once al-Qaida’s takeover of the financing network was complete, Bin Laden’s group had what amounted to a New York clubhouse at the Alkifah Center.

“Prior to that time—1988, ’89—terrorism for all intents and purposes didn’t exist in the United States,” says Corrigan, the retired Joint Terrorism Task Force investigator. “But Abdel-Rahman’s arrival in 1990 really stoked the flames of terrorism in this country. This was a major-league ball player in what, at the time, was a minor-league ballpark.”

In Corrigan’s view, the arrival of Abdel-Rahman was “a real coup for the local cell members like Shalabi, Nosair, Abouhalima, and Ayyad.” Before long, as court documents show, Abdel-Rahman was preaching at three separate mosques: the Abu Bakr on Foster Avenue in Brooklyn; the Al-Salam, located on the third floor of a dingy Jersey City building; and the Shalabi-connected al Farooq Mosque on Atlantic Avenue. At first, Shalabi welcomed the sheikh with open arms—even installing him in a Brooklyn apartment. But their warm relationship wouldn’t last very long. Abdel-Rahman coveted the cash rolling into the Alkifah—as much as $2 million, a year according to The New Yorker’s Mary Ann Weaver, but no one knows for sure. In any case, as the months went by, Abdel-Rahman began quarreling with Shalabi openly in the mosques.

***

By the fall of 1990, one of the Calverton trainees was growing more and more restless. El Sayyid Nosair, the janitor who worked in the courthouse basement, had joined Abdel-Rahman’s ultra-violent Islamic Group, or Al Gamma Islamyah, and he was itching to make his bones for the jihad. The newly uncovered FBI documents reveal a confession by Nosair that on the night of the Kahane murder he was aided by Alkaisi, then a 25-year-old Jordanian immigrant who worked as a cab driver in New Jersey and instructor at the al Farooq Mosque.

Describing Alkaisi as “a veteran of jihadist activity overseas,” including Afghanistan, Nosair told the feds that the two of them entered the Marriott East Side and that, just after Kahane had finished speaking, Nosair exclaimed, “This is the moment.” He then lunged forward with the same chrome-plated .357 Magnum photographed by the FBI at Calverton and fired the single shot that hit Kahane in the neck, blowing him to the floor.

As I later learned from Alkaisi’s former attorney, Robert L. Ellis, Alkaisi “left the Marriott and escaped by way of the subway station at 51st Street and Lexington Avenue.” Meanwhile, as Nosair rushed from the conference room, he was grabbed by Irving Franklin, a 73-year-old Kahane supporter. After a brief scuffle, Nosair shot the old man in the leg and raced toward the hotel’s front door, searching for a taxi.

His intended getaway driver was Mahmoud Abouhalima, who had been waiting outside, but moments earlier, the doorman had waved him away from the entrance, according to reports. So when Nosair ran from the hotel, he mistakenly got into a taxi driven by Franklin Garcia, a New York City cabbie. Suddenly, a young follower of Kahane jumped in front of the cab and prevented it from moving.

In the back seat, Nosair realized the error and pointed the barrel of the .357 at Garcia’s head, whereupon the taxi driver burst from the cab. Nosair then exited the taxi and ran down Lexington Avenue with the gun, where he was spotted by Carlos Acosta, a uniformed U.S. postal inspector, who drew his service weapon. Nosair fired first, wounding Acosta in the shoulder, just outside the edge of his flak vest, but the heroic officer dropped to his knee and returned fire as Nosair started to run, striking the Egyptian with a single shot. A pair of ambulances rushed both Nosair and Kahane to Bellevue Hospital’s trauma unit, where they were operated on in parallel stalls. The shooter survived; Kahane did not.

***

Later that night, Abouhalima and Mohammed Salameh (another Calverton shooter) regrouped at Nosair’s home in Cliffside Park, New Jersey. But they were soon taken into custody as material witnesses by New York police after the house was raided. According to a series of FBI documents, detectives and FBI agents also seized 47 boxes in the raid—material that included prima facie evidence of an international bombing conspiracy with the World Trade Center as a target. Among the files seized was a potential hit list of prominent Jewish figures, including federal judge Jack B. Weinstein, a legendary jurist known as “the lion of the Eastern District.”

The seized material also contained documents presumably left by Ali Mohamed, including Green Beret training manuals and communiqués from the Joint Chiefs of Staff that investigators believe he’d pilfered from Fort Bragg, a sign of al-Qaida’s intent to attack strategic U.S. targets. There was a Joint Chiefs of Staff “Warning Order,” addressed to eight separate U.S. military command centers, the White House, and the Defense Intelligence Agency, plus the U.S. embassies in Egypt, Sudan, Somalia, and Saudi Arabia.

The presence of these documents, many labeled “top secret for training,” not to mention Abouhalima and Salameh, suggested a conspiracy in the Kahane murder. Yet the very next day, NYPD Chief of Detectives Joseph Borelli concluded that the killing was a “lone-gunman” shooting. “There hadn’t been any political assassinations in New York in more than a decade and Borelli didn’t want one on his watch,” Newsday reporters Jim Dwyer, David Kocieniewski, Diedre Murphy, and Peg Tyre wrote in their book on the World Trade Center bombing, Two Seconds Under the World.

Although the raid on Nosair’s house was conducted by New York police and the FBI—which had the Calverton photos not just of Nosair but also of Abouhalima and Salameh—the latter two were released within hours and never charged in the crime.

***

By the summer of 1990, just about when Shalabi picked up Abdel-Rahman at JFK, the Brooklyn Alkifah Center was grossing more than $100,000 per month in cash for the “struggle.” So when Nosair was arrested, Shalabi took it upon himself to raise the money for his legal fund, particularly after star attorney William Kunstler signed on for the defense. By the time Nosair’s trial began in late 1991, $163,000 had poured in—$20,000 of which, court documents would later show, came from Osama Bin Laden, who had been contacted by Nosair’s cousin.

But Shalabi was intent on making his own decisions. While respectful of al-Qaida, the terror network that had consumed the financing system known as MAK, Shalabi remained loyal to Abdullah Azzam, his old mentor, who had wanted to use the money to set up a Taliban-like government in Afghanistan. That put him in direct conflict with Bin Laden and the Egyptians around him, who wanted the funds to be used for the worldwide jihad. And even though Shalabi himself sponsored Abdel-Rahman’s visa entry into the United States, he balked when Abdel-Rahman demanded that some of the Alkifah’s monthly income be used for a fund to help overthrow Hosni Mubarak in Egypt.

And so by the late summer of 1990, tensions were mounting between Shalabi and Abdel-Rahman. In the Brooklyn-based Abu Bakr Mosque, Abdel-Rahman began denouncing Shalabi openly as a “bad Muslim.” Abdel-Rahman even suggested that his fellow Egyptian was embezzling the Alkifah’s funds. Handouts were circulated under the Sheikh’s name. “We should not allow ourselves to be manipulated by his deviousness,” the leaflets said. Other handouts included mini fatwas declaring that Shalabi was “no longer a Muslim.”

Soon Shalabi began to fear for his life.

Continue reading: A murder case reopened. Or view as a single page. According to former FBI agent Jack Cloonan, who debriefed Ali Mohamed—the former Egyptian-commando-turned espionage agent—after his arrest, Shalabi made the mistake of confiding in Mohamed and asking his help so that he could escape home to Egypt with his family. As Cloonan tells it, Mohamed actually drove Shalabi’s wife, Zanib, to the airport and made plans to move her husband back home. At least that’s how he presented himself to the increasingly terrified Alkifah director. On February 26, 1991, on the eve of the first Gulf War, Shalabi hurriedly packed for a flight to Cairo, where his family was waiting. That was the last time his loved ones saw him alive.

A few days later, a neighbor of Shalabi’s noticed that the door to his Seagate, Brooklyn, apartment was open. Ali Mohamed’s former confidant was sprawled on the floor. “He was knifed, shot, and beaten with a baseball bat,” says former Joint Terrorism Task Force investigator Tommy Corrigan. “This wasn’t some genteel thing. He was made an example of.”

Detectives from the NYPD’s 60th Precinct, which covers that section of Brooklyn, took control of the crime scene. In the course of their investigation, they discovered that more than $100,000 in Alkifah cash was missing from the apartment. Mahmoud Abouhalima, Mohamed’s redheaded former student at Calverton, came in and identified the body—falsely claiming that he was the victim’s brother.

Forensic investigators found two red curly hairs clutched in the corpse’s hand, but Shalabi himself was a redhead so that lead proved inconclusive. Neither Abouhalima nor the Abdel-Rahman was ever charged in the murder. In any case, the brutal Shalabi slaying, coming after the 1989 killing of MAK founder Abdullah Azzam, represented the final takeover of the MAK financing network by Osama Bin Laden and his Egyptian entourage. “At the time,” says Corrigan, “Nobody realized how important the Alkifah Center was. It was basically a direct link from al-Qaida right into New York.”

Shalabi’s murder remained an open “cold case” in the files of the 60th Precinct until the end of June of this year, when I uncovered a series of standard FBI interview reports, known as “302 memos.” These 302s from the Joint Terrorism Task Force not only identified the second gunman in the Meir Kahane assassination as Bilal Alkaisi but also named him as the lead killer in the three-man team that killed Mustafa Shalabi.

The NYPD Reopens the Murder Case

In order to appreciate the significance of those 302s, we need to go back to the story of Emad Salem and how he first infiltrated the cell around the blind Sheikh, Omar Abdel-Rahman, responsible for both murders as well as the 1993 Twin Towers bombing and the “Day of Terror” plot.

In the fall of 1991, Salem was recruited by an alert FBI agent named Nancy Floyd. He’d begun hanging out amid the throng of protesters supporting El Sayyid Nosair during his trial for the Kahane killing. Within weeks, Salem had done such a convincing job of proving his loyalty to the jihad that he’d become Abdel-Rahman’s bodyguard. According to trial testimony, he even drove the spiritual head of al-Qaida in the United States on a fund raising tour of mosques in Detroit in a van furnished by the FBI.

With William Kunstler as his attorney, Nosair beat the Kahane murder rap. He was convicted only on minor weapons charges after witnesses at the Marriott failed to identify him. Still, Judge Alvin Schlesinger, who presided at the trial, handed down the maximum sentence, and Nosair was sent to Attica State Prison.

By May 1992, working with Nancy Floyd and his two other control agents, Det. Lou Napoli of the Joint Terrorism Task Force and Special Agent John Anticev, Emad Salem began sensing that the followers around Abdel-Rahman were conspiring to wreak further “havoc” in New York City. Napoli and Anticev had learned that Nosair had become a member of the Islamic Group, Abdel-Rahman’s Egyptian-based terror organization, which had merged with al-Qaida. So Salem began visiting Kahane’s killer in Attica. There Nosair hatched what the FBI later called the “12 Jewish locations plot”: a wide-ranging conspiracy to bomb the Diamond District and a series of New York synagogues.

“Target the Jews,” Nosair told Salem, during one of his prison visits, mentioning specifically Judge Schlesinger, who had sentenced him, along with Brooklyn Assemblyman Dov Hikind. “He was not merciful with me,” said Nosair, according to trial testimony, “and we should have no mercy with him.” Nosair went so far as to suggest that Salem kidnap the judge or “maybe even shoot him,” details Salem dutifully reported back to his handlers at the FBI.

But after months undercover, Salem was, according to Napoli, effectively forced out of the cell by Carson Dunbar, an ex-New Jersey State Trooper who had just become the head of the Joint Terrorism Task Force. Despite risking his life for the FBI for months and furnishing invaluable intel, Salem was mistrusted by Dunbar, who insisted that he wear a wire. Given that he was sleeping on the floors of mosques and could easily have had his cover blown if taping equipment was discovered, Salem was forced to remove himself from Abdel-Rahman’s cell.

Years later when I interviewed him, Dunbar insisted that Salem was “a prolific liar,” and an informant who was “out of control.” But Corrigan underscored the significance of Salem’s removal from the cell. “The withdrawal of Emad really hurt us a lot,” Corrigan told me in an interview with him for Triple Cross. It was also a move that left the “nest of vipers” around Abdel-Rahman without a bomb maker.

So once Salem was out, they called in Ramzi Yousef, a Baluchistani raised in Kuwait who had earned an engineering degree in Wales. On February 26, 1993, six months after Salem left the cell, Yousef set off a 1,500-pound bomb on the B-2 parking level below the Twin Towers. He’d built it with the help of Abouhalima, Salameh, and Ayyad, three of the Calverton shooters the FBI had under surveillance in July of 1989.

For the Playboy piece, Salem provided me with a tape that he’d made with his FBI control agent John Anticev after the bombing. “If we was continuing what we were doing, the bomb would never go off,” Salem tells Anticev in broken English. At that point, the FBI agent replies: “Absolutely. But don’t repeat that.” As I see it, this is the first concrete admission by an FBI agent that the bureau could have stopped the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.

Days later, even though he’d been vastly unappreciated by the management in the bureau’s New York office, Salem volunteered to go back undercover, this time with a wire. As the feds’ linchpin witness in the “bridge and tunnel” case, Salem provided testimony that led to the conviction of Abdel-Rahman and nine others in 1995. In that same trial the feds succeeded in convicting El Sayyid Nosair for Kahane’s murder after the Manhattan D.A. had only convicted him on gun charges.

In one of our interviews, Salem told me that during an undercover conversation in 1993, Clement Hampton-El, a member of the Calverton shooting cell, had told him that a .22 pistol was used to kill Mustafa Shalabi, the Egyptian who had run the Alkifah Center at the al Farooq Mosque. Hampton-El, who was later convicted in the “Day of Terror” plot, also told Salem that, after the bloody killing, Shalabi’s body was moved in such a way as to “make it look like the Jews did it.”

These two details, which have never before been made public, reminded me of something I had previously learned from an FBI source: During the Kahane trial, William Kunstler had received a single bullet in the mail—a threat intended to get him off the case. The bullet, purportedly sent by Kahane’s supporters in the Jewish Defense League, was a .22. Could it be that this threat to Kuntsler had actually come from the killers who, once again, sought to blame the homicide on “the Jews”?

***

In 1993, the FBI reopened the Shalabi case and leaked information that led to a series of stories in The New York Times identifying Hampton-El, Mahmoud Abouhalima, and Mohammed Salameh as possible suspects, I learned in my research. The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York even subpoenaed witnesses to a Shalabi grand jury. But for reasons unknown until now, the FBI dropped the case, and it stayed “cold” until this past winter.

In mid-February, with the new details furnished by Salem, Det. James Moss, of the NYPD Brooklyn South Homicide Squad, began kicking over rocks and searching for the forensic evidence from the 1991 Shalabi crime scene. By late May, Moss discovered that this key evidence, once stored in the police department’s property clerk’s office, had been signed out by an investigator for the Joint Terrorism Task Force in October 1993.

That was around the time the FBI had shown renewed interest in the case. I soon learned through a source that the investigator who removed the evidence was none other than Tommy Corrigan—the same Joint Terrorism Task Force investigator who had been present during the 1989 Calverton surveillance of Abouhalima, Salameh, Hampton-El, and Nidal Ayyad, the Kuwaiti émigré and Rutgers grad convicted in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing for having supplied chemicals to the cell.

Corrigan went on to work closely with I-49, the so-called “Bin Laden Squad” in the FBI’s New York Office, which was the principal FBI squad supporting al-Qaida prosecutions in the Southern District of New York—from the World Trade Center bombing case, tried in 1994, through the East African U.S. embassy bombings case, tried in 2001. What were the odds that of the nearly 100 law enforcement officers assigned to the Joint Terrorism Task Force, Corrigan, the one cop who had been present at the original surveillance of these cell members, would confiscate the evidence from the New York police? When I tried to reach Corrigan, who has since retired, I couldn’t get through to him.

But by June, Moss, the Brooklyn detective, had hit a brick wall: The forensic evidence could not be located, and his investigation would be severely hampered without it. So I sent the first in a series of detailed emails to the Intelligence Division of the New York Police Department, asking them to contact the FBI for the return of the evidence seized by Corrigan. On June 30, according to a confidential source, the FBI coughed up a series of interview memos, called 302s, dating from 2004 to 2006, which shed extraordinary new light on both the Shalabi and Kahane murders. Among the revelations was the fact that Bilal Alkaisi, the Jordanian cab driver who assisted Nosair during the Kahane hit, was also the lead killer in the Shalabi murder.

But perhaps most important, these memos, taken together with a 1996 FBI memo I obtained, prove a link between Osama Bin Laden and the Meir Kahane assassination.

Continue reading: Undisclosed FBI Files. Or view as a single page. Undisclosed FBI Files Show al-Qaida’s Links to Both Murders

In a series of confessions given to Joint Terrorism Task Force investigators and Southern District of New York prosecutors, Ayyad, the Kuwaiti immigrant who worked at Allied Chemical in New Jersey, described how he was the wheel man of the three-man Shalabi hit team including Palestinian Mohammed Salameh and Jordanian Bilal Alkaisi. He tells of how the trio gained entry to Shalabi’s home in a gated community that February night in 1991. At the time, fearing for his life after being denounced by Abdel-Rahman, Shalabi was preparing to flee back to Egypt.

As Ayyad describes it to the FBI in gruesome detail, Salameh, using a silenced .22 provided by Alkaisi, followed Shalabi into his kitchen and shot him twice in the head but, after the gun jammed, the big Egyptian got up and chased the diminutive Palestinian. At that point, Alkaisi pulled out a knife and began stabbing Shalabi, whereupon Salameh put a new magazine in the gun and fired four more shots, finishing the job. The three fled the bloody crime scene leaving Shalabi with 30 puncture wounds from Alkaisi’s blade.

The murder took place precisely two years to the day before the World Trade Center blast executed by Ramzi Yousef, whose uncle is Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, the man the FBI calls the mastermind of the Sept. 11 plot. Despite multiple stories in The New York Times during the spring, summer, and fall of 1993—that the Shalabi case had been reopened and a grand jury was hearing evidence in the investigation—the New York Office of the FBI and prosecutors in the Southern District of New York seemed to lose interest in the case by 1994. The question is why.

Another important question is why the FBI began pursuing the case in 2004 with multiple interviews of Nosair and Ayyad over the next two years. And in the post-Sept. 11 era, when counterterrorism agencies were supposed to end the “stove-piping” and intelligence hoarding that failed to prevent the Sept. 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, why did the Joint Terrorism Task Force keep the confessions a secret?

“It could be that they were embarrassed,” said one ex-FBI agent I interviewed after obtaining the Ayyad-Nosair 302s. “If you read those confessions, it’s clear that Alkaisi wasn’t just some minor player. He was a major operative—and, as Ayyad tells it with great credibility—the ring leader in the Shalabi murder. On top of that, the confessions from Nosair indicate that Alkaisi played a leadership role in the Kahane hit as well.”

The Bigger Embarrassment: Bilal Alkaisi’s Release

Alkaisi had turned himself in at the FBI’s Newark office on March 24, 1993, almost a month after the World Trade Center bombing. Evidence developed by the FBI in what was called the TRADBOM investigation revealed that Alkaisi shared not only an apartment in Jersey City with Salameh, but also a bank account, through which more than $100,000 was funneled to help finance the bombing conspiracy. When Ayyad was arrested, he was carrying a credit card with Alkaisi’s name on it.

Further, according to an interview I conducted with Robert L. Ellis, Alkaisi’s attorney at the time, the Jordanian cab driver had initially been identified by a security guard at the Space Station storage locker in Jersey City where the Yousef-Abouhalima-Salameh cell stored the chemicals furnished by Ayyad that they used to build the bomb.

On March 25, 1993, Southern District prosecutors charged Alkaisi with “aiding and abetting” the Trade Center blast and ordered him held without bail. Special Agent Jim Esposito of the FBI’s Newark office, where Alkaisi had turned himself in a day earlier, told reporters that Alkaisi was seen “on several occasions” at the storage locker rented by Salameh—a location, federal agents claimed, where the bomb chemicals were mixed. Federal officials later admitted that after walking into the Newark FBI office, Alkaisi waived his rights and was questioned for three hours by agents.

Alkaisi was finally charged in the bombing on April 7 and entered a not guilty plea a week later. Four days after that, he hired Ellis to represent him. Curiously, unlike some of the other defendants, Alkaisi’s legal fees were being paid for by a defense fund financed by several area mosques.

By late May, The New York Times was reporting that “fingerprints later found inside a Newark safe-deposit box showed that Mr. Salameh and Mr. Alkaisi had access to it, according to an F.B.I. report. And investigators have found that close to $100,000 had been wired to several bank accounts linked to the suspects, some of the money from Iran.”

It was widely reported that Alkaisi worshipped at the al Farooq Mosque on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn and the Al-Salam Mosque in Jersey City, two places where Abdel-Rahman preached his fiery sermons. At a trial, federal agents would describe Abdel-Rahman as the leader of the “jihad army” responsible for the World Trade Center blast and the “Day of Terror” plot.

But by early August of 1993, the feds had begun to shift their focus away from Alkaisi as a key player in the Trade Center bombing conspiracy. Prosecutors acquiesced to a request by Ellis that Alkaisi be tried separately, and the young Jordanian’s name was missing from the latest bombing conspiracy indictment. Then, just days before jury selection, Ellis told me, federal agents dropped their own bomb.

“I received a call from Gil Childers, the lead federal prosecutor, who informed me that he was not proceeding against Alkaisi,” Ellis said, making this disclosure in a July interview after I’d uncovered Ayyad’s confession.

By early March of 1994, after a five-month trial, federal prosecutors had their victory, convicting all four suspects in the Twin Towers bombing. Curiously missing from the courtroom at the time of the verdicts was the man who had roomed with Salameh, shared a bank account with him, and had reportedly been spotted at the storage locker where the bomb’s lethal cocktail of chemicals was mixed. At that point, attorney Ellis was telling reporters that he was hoping to “settle” Alkaisi’s case without trial. And two months later, that’s exactly what happened. On May 9, prosecutors allowed Alkaisi to plead guilty to a minor immigration charge.

Despite the fact that in earlier indictments Alkaisi had been tightly tied into the World Trade Center bombing conspiracy with Abouhalima, Salameh, and Ayyad, Mary Jo White, then U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, now claimed that the government didn’t have the evidence “to obtain a sustainable conviction” against him “beyond a reasonable doubt.” She insisted that federal prosecutors had “made no promises or agreements not to bring new charges against the defendant.” After serving 18 months of his 20-month sentence, Alkaisi was released and deported.

The Southern District gave Alkaisi what amounted to a wrist slap and cut him loose, but additional evidence I’ve uncovered suggests that the feds viewed him as an important al-Qaida-related operative.

In February 1994 Alkaisi was named No. 20 on a list of 172 “un-indicted co-conspirators” in the “Day of Terror” case—a list compiled by Southern District of New York prosecutors Andrew C. McCarthy and Patrick Fitzgerald. A Who’s Who of terrorists and radical Islamic sympathizers with links to the Trade Center bombing and the “Day of Terror” plot, the list included Osama Bin Laden (No. 95), Mustafa Shalabi (No. 149), Ali Mohamed (No. 109), and Bin Laden’s brother-in-law Mohammed Jamal Khalifa (No. 86), the man who would later bankroll the Yousef-Khalid Sheik Mohammed Manila cell that spawned the Sept. 11 plot. Why would McCarthy and Fitzgerald have included Alkaisi on the list if he was a minor player whom the government didn’t think significant enough to try?

Fitzgerald, now U.S. Attorney in Chicago, is the former special prosecutor in the Valerie Plame CIA leak case who moved a court to jail New York Times reporter Judith Miller for 85 days in 2005 and most recently secured a single conviction against Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich on corruption charges. But in the fall of 1996 when he was co-head of the Organized Crime and Terrorism Unit in the Southern District of New York, Fitzgerald was directing Squad I-49, in the FBI’s New York Office, which was building a case against the Saudi billionaire.

The al-Qaida Link to the Meir Kahane Assassination

Earlier that year, Jamal al-Fadl (aka Gamal Ahmed Mohamed Al-Fedel), a 33-year-old Sudanese émigré, walked into the U.S. Embassy in Eritrea. Later dubbed “Junior” by prosecutors, al-Fadl had worked directly under Mustafa Shalabi at the Alkifah Center, and then, at Shalabi’s behest, fought in Afghanistan and later swore an oath to the new terror network called al-Qaida before moving to Khartoum, in Sudan, where he worked side by side with Bin Laden as his assistant.

Having embezzled funds from al-Qaida, al-Fadl was looking to cut a deal with U.S. authorities, so Fitzgerald traveled to Germany with FBI agents to debrief him. Fitzgerald would later use the young Sudanese man as his key witness against Bin Laden in the 2001 African Embassy bombing case. The extraordinary details of Fitzgerald’s al-Fadl debriefing are contained in an 18-page FBI 302 memo that I obtained. It’s labeled “Particularly Sensitive.”

This epic 302 not only documents a near-straight line from the al Farooq mosque in Brooklyn to the Trade Center bombing and “Day of Terror” cells, but it also links to the Ramzi Yousef-Khalid Sheikh Mohammed Manila cell that designed the Sept.11 “planes operation” via Wali Khan Amin Shah; aka Osama Asmurai. An Uzbeki whom Bin Laden called “the Lion,” Shah was later convicted with Yousef in the so-called “Bojinka” plot to plant bombs on a dozen U.S.-bound jumbo jets exiting Asia.

Al-Fadl told Fitzgerald that he worked with Khan-Asmurai in Afghanistan for several months, after he had been sent there by his mentor and emir Mustafa Shalabi.

Shalabi is mentioned on multiple pages of that 302 memo, offering some indication of Patrick Fitzgerald’s interest in his death. But what is particularly telling is that two years after being cut loose by federal authorities, Bilal Alkaisi was considered important enough by Fitzgerald to include on a list with the most dangerous al-Qaida players known to the FBI at that time. According to the 302, at the end of the debriefing, Fitzgerald showed al-Fadl 77 photos with the pictures of key al-Qaida operatives, including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Yousef, Shah, Ali Mohamed, Ayyad, Abouhalima, Salameh, Nosair, and Hampton El.

No. 19 on that list was a picture of Bilal Alkaisi.

In his confession to the federal agents on December 20, 2005, documented in one of the recently discovered FBI 302s, El Sayyid Nosair admits that he did a surveillance of a New York airport in anticipation of the Kahane hit with a man named Ephron Gilmore, an American Muslim U.S. Army vet whose nom de guerre was “Tahir.” That very same operative was identified by Jamal al-Fadl in his 1996 confession to Fitzgerald as “Tehar.” In fact, al-Fadl told Fitzgerald that “Tehar” was working for Bin Laden and that he saw him at a meeting with the Saudi billionaire and Abu Ubaidah al-Banshiri, a top-level al-Qaida leader reported killed in 1996.

Taken together, these two 302 memos referencing the involvement of Gilmore (aka Tehir/Tehar) show a link between Osama Bin Laden and the rabbi’s death. For a case tried by the Manhattan D.A. as a “lone-gunman” killing, that is big news.

“If we’d known that three of the guys who went on to bomb the World Trade Center had killed Shalabi, that would have enhanced our sense of their bench strength much earlier,” said Lt. Col. Anthony Shaffer, a principal in Operation Able Danger, the 1999-2000 al-Qaida data-mining operation conducted by the Defense Intelligence Agency. Able Danger, based at the Army’s Land Warfare Information Activity at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, would later find links between four Sept. 11 hijackers and what was described as a “Brooklyn-based cell” associated with the al Farooq mosque.

***

Some of the questions raised by all of this are as old as Watergate: What did the feds know about these acts of terror and when did they know it? It’s clear that Southern District prosecutors thought the Shalabi homicide investigation important enough to reopen it and subpoena witnesses before a grand jury in 1993. The Joint Terrorism Task Force thought it important enough to remove key forensic evidence from the NYPD’s property clerk’s office that October. Federal agents leaked stories to The New York Times that cited Mohammed Salameh as a possible suspect. Yet for unknown reasons, they shut the investigation down in 1994 and didn’t effectively reopen it again for another decade.

Why did it take a revelation by Emad Salem to an investigative reporter almost 20 years after the Shalabi death to connect the dots? Even more disturbingly, given what these newly uncovered FBI 302s tell us about the Kahane and Shalabi murders, why would the Joint Terrorism Task Force keep those confessions hidden from New York police almost a decade after Sept. 11, when intelligence sharing between counterterrorism agencies has become a mandate?

It’s now clear that Bilal Alkaisi was a linchpin connecting the Kahane assassination with the World Trade Center bombing, effectively recasting Kahane’s significance, if not in life, then in the manner of his death. In my books, I prove a direct connection between Ramzi Yousef’s first Trade Center attack in 1993 and the “planes as missiles” plot executed on Sept. 11, which was designed by Yousef in Manila in 1994 and executed by his uncle Khalid Sheikh Mohammed in 2001. What more could other U.S. intelligence agencies like the CIA, the Defense Intelligence Agency, and the National Security Agency have learned, in the years leading up to the Sept. 11 plot, if the full truth behind the rabbi’s murder and its place in Bin Laden’s decades-long plot to attack the United States had been known?

And there’s a more immediate question: What, if anything, does the New York Police Department intend to do about Bilal Alkaisi? With these confessions, now public, will the Brooklyn D.A. issue a murder warrant for the Jordanian national, who is still presumably at large? We don’t know if he’s alive or dead. The NYPD’s public information office has refused my multiple requests for a response. The district attorney’s office says it’s still studying the matter. And the FBI, as it has with all of my findings, remains mute.

Peter Lance, the author of Triple Cross, Cover Up, and 1000 Years for Revenge, is an investigative reporter and former correspondent for ABC News.

Recent Comments