Recent Posts

- Get HOMICIDE in four editions. Rated No.1 among The Five Best Crimes Biographies of All Time

- Peter Lance Biography

- HuffPost: DOJ report on MISSBURN case leaves out key detail: I.D. of the Mafia killer who broke the case for Hoover’s FBI

- On Halloween in 1994 CBS aired a new take on Orson Welles’ radio classic “War of The Worlds.” With 225,000+ views, it’s now become a YouTube cult favorite as well.

- Jason Leopold calls TRIPLE CROSS a “9/11 masterpiece”

Archives

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- March 2024

- January 2024

- November 2023

- June 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- September 2019

- April 2019

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- September 2017

- June 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- June 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- November 2010

- October 2010

- March 2010

- August 2009

- November 2006

- November 2004

- October 2003

- September 2003

- February 2000

Categories

- 1000 Years for Revenge

- ABC's Path to 9/11 issue

- Ali Mohamed

- Ali Mohamed revelations

- Anwar al-Awlaki

- ARCHIVES

- awards

- bio

- BIOGRAPHY

- BOOK TV C-SPAN2

- BOOK WRITING

- BOOKS

- Colombo family "war"

- Commentary

- DUI investigation

- Emad Salem investigation

- FBI ORGANIZED CRIME

- Featured

- FICTION

- First Degree Burn

- Fitzgerald censorship attempt

- Fitzgerald censorship scandal

- Fox News

- Gotham City Insider

- Gregory Scarpa Jr.

- Gregory Scarpa Jr.

- Gregory Scarpa Sr.

- Harpercollins

- HUFFINGTON POST

- INVESTIGATIONS

- Khalid Shaikh Mohammed

- MAGAZINE ARTICLES

- Major Hasan Fort Hood massacre

- MEDIA COVERAGE

- Meier Kahane Assassination

- Meir Kahane assassination

- Murder Inc.

- Nat Geo whitewash

- NEWSPAPER REPORTING

- NOVELS

- Oklahoma City bombing

- Omar Abdel Rahman

- OPERATION ABLE DANGER

- POLICE CORRUPTION

- Produced

- R. Lindley DeVecchio

- Ramzi Yousef

- Ramzi Yousef sting 302's

- REPORTING & ANALYSIS

- RESEARCH

- Santa Barbara News-Press

- SCREENWRITING

- Stranger 456

- Stranger 456

- teleplays

- Tenacity Media

- Triple Cross

- Triple Cross

- TV NEWS COMMENTARY

- Uncategorized

- videos

- WIKIPEDIA

NY Magazine on a former U.S. Attorney’s campaign to bury “Triple Cross.”

PROSECUTOR AS BOOK PUBLICIST By Boris Katchka.

PROSECUTOR AS BOOK PUBLICIST By Boris Katchka.

Patrick Fitzgerald, U.S. Attorney for Illinois’s Northern District, doesn’t pull his punches. Charming, tough, and named one of People’s “sexiest men alive” in 2005, he took down Governor Rod Blagojevich (as well as his predecessor) and got the Times’ Judith Miller imprisoned during the investigation that ended with Scooter Libby’s conviction. Now he’s threatening to take another journalist to court, for defamation and libel. And this time, it’s personal. He’s acting as a private citizen defending his public name.

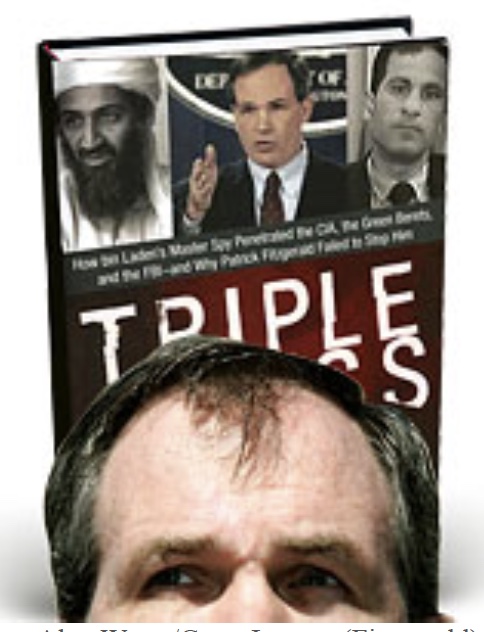

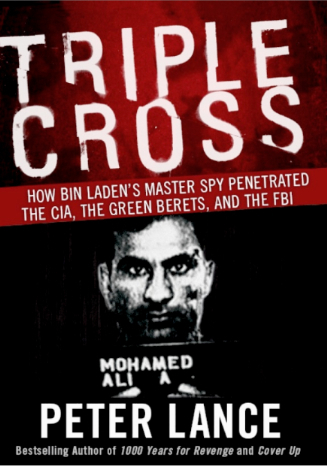

The book in question is Peter Lance’s Triple Cross, which was published in November 2006 by Regan Books, a division of HarperCollins. Lance examines how the FBI and the U.S. Attorney in New York prosecuted terrorists before 9/11, including Sheik Omar Abdel Rahman and those who blew up the U.S. embassies in Africa.

At that time, Fitzgerald worked for the U.S. Attorney in New York. Lance alleges that Fitzgerald discounted information Lance contends arguably pointed to the existence of an Al Qaeda cell in New York five years prior to 9/11. Nearly a year after Triple Cross was published, in the lull between Libby and Blagojevich, Fitzgerald sent an eleven-page letter to HarperCollins (listing a private P.O. box as a return address, to prevent confusion with his official duties). It alleged that “Triple Crossmakes a number of statements of fact which defame me (and others) and which are easily proven to be objectively false.”

He listed a few examples and asked the house to stop selling all hardcovers, refrain from printing another edition, and acknowledge the errors written about him. HarperCollins’s General Counsel wrote back, denying his claims and concluding that “we stand behind Mr. Lance” and would go ahead with the paperback, “which we regard as an important work of investigative journalism.”

Fitzgerald responded with an even longer letter. Thereafter, HarperCollins had a lawyer re-vet the entire book—a process that took fourteen months. Fitzgerald followed up again last September, noting that “surely, HarperCollins can make a decision in a year. And if it cannot feel comfortable proceeding after another eleven months of thought, that ought to tell HarperCollins something about its confidence level in the book.”

Last week, Fitzgerald sent one more letter, which ended with “To put it plain and simple, if in fact you publish the book this month and it defames me or casts me in a false light, HarperCollins will be sued.” But in the end, he backed down and never made good on his threat.

Lance is holding a press conference on the 16th at The National Press Club in Washington, when he’ll be flanked by anti-censorship activist librarian Ann Sparanese and the lawyer played by John Travolta in A Civil Action, Jan Schlichtmann.

In response to a request put through to his office, Fitzgerald called back personally to say he had no comment, adding that on this personal matter, he could be reached only through the P.O. box.

THE CHILLING EFFECT By Peter Lance. playboy.com

In 2002 I left the Philippines with a packet of classified intelligence. The material proved that the Al Qaeda bomb maker who exploded a 1,500-pound urea-nitrate device in the World Trade Center in 1993 was the same terrorist who, two years later in Manila, conceived the “planes operation” realized on 9/11.

Four years to the month after I’d left my meeting with an official of the Philippines National Police, I stood outside the Brooklyn Supreme Courthouse as a phalanx of angry ex–FBI agents surrounded the man once known in the bureau as Mr. Organized Crime. Swatting back the press like a mob of soccer hooligans after a losing match, the former agents were protecting R. Lindley DeVecchio, an ex–supervisory special agent who’d been indicted on four counts of murder.

I had covered DeVecchio in my book Cover Up, which a Brooklyn assistant DA had referred to as the “springboard” for their investigation. Now, as he moved down Jay Street, DeVecchio—just released on $1 million bail—shot me a predatory look.

At that point, I was writing a new book about how Al Qaeda met the mob. This book would soon put me in the crosshairs of the ex-agent’s defense team. Not only did I get subpoenaed and threatened with jail if I didn’t cough up my confidential sources, but after the book was published, the most powerful federal prosecutor in the country demanded it be killed.

I’d become the latest target of Patrick Fitzgerald, the U.S. attorney for Chicago and former special counsel in the CIA leak investigation. I’d raised some questions about his record on counterterrorism, and Fitzgerald, described by a former colleague at Justice as “Eliot Ness with a Harvard degree and a sense of humor,” was not amused.

The man who jailed publishing magnate Conrad Black and got Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich indicted has enjoyed an extraordinary reputation for honesty and integrity, but he’s also used his power to intimidate the media.

The story of how he came gunning for me sheds light on his methods as a prosecutor and calls into question certain decisions he made in the years leading up to 9/11.

The evidence I unearthed stems from Fitzgerald’s tenure in the mid-1990s as co-head of the Organized Crime-Terrorism Unit in the Southern District of New York, the U.S. attorney’s office that turned out Rudolph Guiliani and Louis Freeh.

In 1995, after President Clinton issued Decision Directive 39—a secret order targeting domestic and international terrorism—Fitzgerald was assigned to effectively supervise I-49, the elite bin Laden squad in New York’s FBI office. It would be a career-making position for Fitzgerald, the son of an Irish immigrant doorman.

Fitzgerald soon emerged as the Department of Justice’s leading bin Laden authority. In a February 2006 Vanity Fair profile friends and colleagues described him as a “crusader” with “scary-smart” intelligence and “a mainframe-computer brain.”

Fitzgerald soon emerged as the Department of Justice’s leading bin Laden authority. In a February 2006 Vanity Fair profile friends and colleagues described him as a “crusader” with “scary-smart” intelligence and “a mainframe-computer brain.”

As lead prosecutor in United States vs. bin Laden—the African embassy bombing case in 2001—Fitzgerald went on to become the top federal prosecutor in Chicago, a city well-known for political corruption.

During his current tenure Fitzgerald has amassed what a local reporter called “a remarkable string of courtroom victories,” convicting a host of dirty pols and white-collar criminals including former governor George Ryan and Tony Rezko, an early supporter of Barack Obama.

In December 2003 Fitzgerald was tapped to become special counsel in the Valerie Plame investigation. It would be his job to determine who had outed former CIA operative Plame in an effort to punish her husband for alleging the White House had used false intelligence to justify invading Iraq.

Fitzgerald became a hero for the left, with Bush critics certain the dogged prosecutor with the altar boy image would take the probe all the way to presidential aide Karl Rove or Vice President Dick Cheney. People magazine even named Fitzgerald as one of the “Sexiest Men Alive.” But after 45 months and a multimillion-dollar investigation, Fitzgerald convicted only one man of perjury and obstruction. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, Cheney’s chief of staff, got a 30-month term.

However, the sentence was later commuted by President Bush, allowing Libby to avoid jail. In fact, the only person locked up was Judith Miller, the New York Times reporter, who served 85 days for refusing Fitzgerald’s demands that she turn over her confidential sources.

Miller’s jailing seemed draconian when it was later discovered that Fitzgerald had for some time known the identity of the actual leaker: Richard Armitage, a Bush deputy secretary of state. Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen referred to the months of drama as “a train wreck—mile after mile of shame, infamy, embarrassment and occasional farce.”

The Wall Street Journal called Fitzgerald “a loose cannon.” Progressive columnists worried about his tactics. “Let’s remember that you and I still don’t know exactly why Miller was ordered by the court to go to jail,” wrote Chicago Sun-Times columnist Carol Marin.

“That’s because the written opinion of the U.S. Court of Appeals… contains [eight] blank pages…. [T]he information on those pages has been redacted at the request of U.S. Attorney Fitzgerald…. That level of secrecy in a court ruling has stunned constitutional lawyers.”

Fitzgerald initially went after me in October 2007, 11 months after the publication of my hardcover book. I got a call from Mark Jackson, general counsel for my publisher HarperCollins, who read me a letter he’d just received from Patrick Fitzgerald:

“I write to demand that HarperCollins cease publication, distribution and sale of the current version of [Triple Cross]; issue and publish a clear and unequivocal statement acknowledging that the book contains false statements about me; refrain from publication of any updated version…[and] take no steps to transfer the rights to any other person or entity to publish the book in any form.”

“I write to demand that HarperCollins cease publication, distribution and sale of the current version of [Triple Cross]; issue and publish a clear and unequivocal statement acknowledging that the book contains false statements about me; refrain from publication of any updated version…[and] take no steps to transfer the rights to any other person or entity to publish the book in any form.”

In the letter, Fitzgerald included an attachment requesting that HarperCollins “preserve” 12 separate categories of records, including all “book drafts,” correspondence between me and the publisher and “all records of profits attributable to Triple Cross.”

Black’s Law Dictionary defines a “chilling effect” as a “situation where speech or conduct is suppressed by fear of penalization at the interests of an individual.” Naturally, the level of fear depends on where the threat comes from. When I first got that call, even though I knew my research was bulletproof and Fitzgerald didn’t have a case, the news was, to put it mildly, disturbing.

Fitzgerald had not only succeeded in having a judge jail a reporter for the most influential newspaper in the country, but he’d succeeded in getting her cell phone records in another case. He had 161 lawyers under his command. Although he framed this as a personal complaint, my charges against him related directly to his work for the U.S. Department of Justice. During the next 20 months, he proceeded to send the legal department at HarperCollins 32 pages of threatening letters. In his most recent letter, sent June 2, 2009, he made his intentions clear:

“To put it plain and simple,” he wrote, “if, in fact, you publish the book this month and it defames me or casts me in a false light, HarperCollins will be sued.”

For copies of all four of Fitzgerald’s threat letters and HarperCollins initial response rejecting his claim click here

My book was the first in-depth attempt by a journalist to audit the two principal offices that investigated bin Laden: the SDNY (where Fitzgerald supervised terrorism and mob cases) and the FBI’s New York office (where he developed cases with the bin Laden Squad). It argued that Fitzgerald had been outmaneuvered for years by Al Qaeda’s top spy, Ali Mohamed, and told how he’d discredited a wealth of evidence that might have alerted other agencies to Al Qaeda years before 9/11.

In response to Fitzgerald’s letter, HarperCollins attorney Jackson wrote back, “We stand behind Mr. Lance and intend to go forward with the publication of the updated trade paperback edition of the book, which we regard as an important work of investigative journalism.”

But the U.S. attorney was not satisfied. On November 16, 2007 he sent a second letter demanding that the book be pulped. This time, as if to send a message, it was faxed from the office of the “U.S. Attorney Chicago.”

Last week Newsweek ran a story on Fitzgerald’s threat to sue. In it the U.S. attorney said that he was “not aware” that the “time stamp” on the letter would be visible. But Jan Schlichtmann, the tort lawyer celebrated in the book and film A Civil Action, disagrees. “In my opinion, this was a calculated move by perhaps the most powerful prosecutor in America, designed to intimidate Peter Lance’s publisher.”

In order to mount a successful claim for libel, Fitzgerald would have to prove not only that the statement was false, but that it was written with malice, defined by the Supreme Court in New York Times vs. Sullivan as “reckless disregard for the truth.”

Triple Cross ran 604 pages in hardcover. It had 85 pages of appendixes and supporting documents—including 1,420 end notes. Virtually every factual allegation was annotated.

There were multiple citations from the five terror trials prosecuted by Patrick Fitzgerald’s own Southern District office. Nonetheless, Fitzgerald has succeeded in holding up the paperback’s publication for more than 20 months.

My reporting established that agents of the FBI’s elite Joint Terrorism Task Force had blown multiple chances to stop Ramzi Yousef in the fall of 1992 as he built an urea-nitrate bomb in Jersey City. On February 26, 1993 Yousef set off the bomb in the B-2 parking level beneath the Twin Towers, killing six and injuring 1,000.

After escaping New York that evening, Yousef ultimately made his way to Manila, where he hatched three plots with his Al Qaeda cell: a plan to kill Pope John Paul II during a 1995 visit to the Philippines, the so-called Bojinka plot in which small improvised explosive devices would be placed aboard a dozen U.S. jumbo jets exiting Asia and the “planes operation” in which airliners would be used as suicide bombs in the U.S.

“ The SDNY had more than five years’ prior warning of Ramzi Yousef’s hijacking scenario. ”

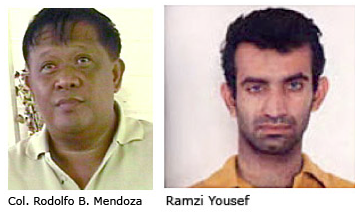

Back on my trip in 2002 I’d received classified evidence about Yousef’s Manila plans from Colonel Rodolfo B. Mendoza of the Philippines National Police. I was shocked to find that Mendoza had sent the same intel in 1995 to the U.S. embassy in Manila, where it was forwarded to prosecutors in the Southern District.

I had traced the chain of custody, interviewing the U.S. Diplomatic Security Service agent who picked up the intel from Mendoza at Camp Crame in Manila and stood by as the FBI legal attaché at the U.S. embassy sent it to the SDNY. The agent confirmed an earlier account he’d given that Mike Garcia and Dietrich Snell, the assistant U.S. attorneys who later prosecuted Yousef, “almost certainly had access to the materials.” By December 1995 Garcia and Snell were working directly under Patrick Fitzgerald.

In short, the SDNY had more than five years’ prior warning of Ramzi Yousef’s hijacking scenario.

My findings created such a stir that Chairman Thomas Kean asked me to testify before the 9/11 Commission.

But when I came to present the evidence I’d received from Mendoza, the senior counsel assigned to interview me was Dietrich Snell, the ex-SDNY prosecutor who should have had access to Mendoza’s intelligence warning.

As I saw it, Snell should have been a witness before the commission, not one of its senior counsels. On March 15, 2004 he led me into a windowless conference room at 26 Federal Plaza, the commission’s New York office. There was no stenographer present and no recording equipment.

Nevertheless, I testified to what I’d learned from Mendoza: In early 1995, after a fire in their Manila apartment, Yousef and his uncle, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, had escaped to Pakistan. But a third member of their cell, Abdul Hakim Murad, had been caught. Mendoza learned that Murad was a commercial pilot trained at four U.S. flight schools. Murad also stated he was more than willing to die at the controls as part of the suicide hijacking plot. At that point, Yousef and KSM had chosen seven targets: the WTC, the Pentagon, the White House, CIA headquarters, the Sears and Transamerica towers and a nuclear facility.

I couldn’t help but feel that Snell seemed to have an agenda as he took notes on my testimony. A source inside the commission staff later revealed to me that Snell and other investigators were working on a scenario that took Ramzi Yousef out of the plot.

Why would they do that? Here’s my theory: Confirming Yousef’s involvement would raise questions about whether the SDNY and FBI had been tipped off to the plot in 1995. They might also be held accountable for failing to stop him in 1992 as the Al Qaeda bombmaker plotted the first WTC attack.

In the end Snell reduced my testimony to a single footnote in the commission’s final report. Ignoring Mendoza’s findings, he cited a meeting between Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Osama bin Laden in 1996—a date after Yousef’s arrest—as the genesis of the 9/11 plot. Most important: Snell’s sole authority for this rewrite of history was Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who Snell, per the 9/11 Report, claimed had confessed after his capture.

To me, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was completely unreliable, particularly since he had been waterboarded 183 times in March 2003. (Recently, Robert Windrem published the results of his exhaustive study of the 9/11 Commission Report. Windrem showed that an astonishing 25 percent of the end notes documenting the commission’s findings were derived from the testimony of prisoners who had been subjected to torture such as water boarding.)

But in spring 1996, KSM was still on the loose, working to execute Yousef’s plot. Meanwhile, Yousef and Murad had been rendered back to the SDNY for the Bojinka trial. One of the prosecutors assigned to the case was Dietrich Snell, then working directly under Patrick Fitzgerald.

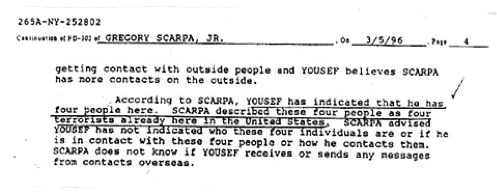

Yousef and Murad were housed on the ninth floor of the Metropolitan Correctional Center. That’s where events began to unfold that led to a crucial Fitzgerald decision. Adjacent to their cells was Gregory Scarpa Jr., the son of a notorious capo for the Colombo crime family.

Though Greg Jr. was a mid-level wiseguy, his father had been jailed for only 30 days in a 30-year career of murder and racketeering. Why? Because in the early 1960s the elder Scarpa had become a Top Echelon informant for the FBI. It’s not surprising that Greg Jr. figured he could rat out these two terrorists and help his cause when he came up on RICO charges.

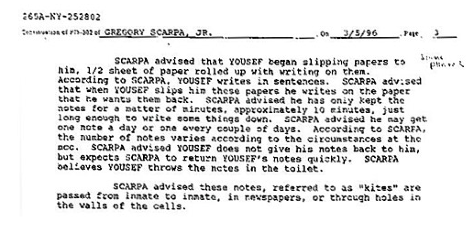

After Yousef and Murad removed bed struts from the walls of their cells they began passing notes, known as kites, through Greg Jr., who acted as middleman. Among the kites was a protocol for a Bojinka-like plot entitled “How to Smuggle Explosives Into an Airplane.” (Many of the notes and the FBI 302 memos that describe them can be accessed here.)

After Yousef and Murad removed bed struts from the walls of their cells they began passing notes, known as kites, through Greg Jr., who acted as middleman. Among the kites was a protocol for a Bojinka-like plot entitled “How to Smuggle Explosives Into an Airplane.” (Many of the notes and the FBI 302 memos that describe them can be accessed here.)

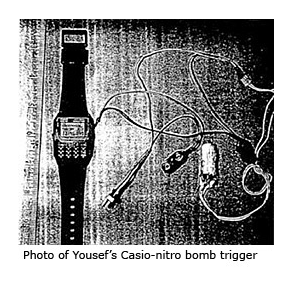

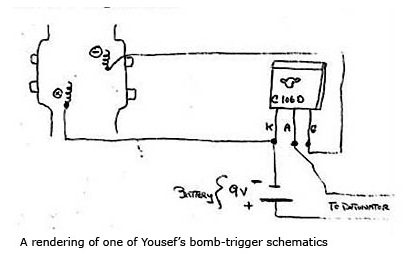

Scarpa Jr. also retrieved a schematic from Yousef that showed how a Casio DBC-61 Databank watch could be soldered into a C106D semi-conductor. That schematic matched copies of a Casio IED recovered from Yousef’s Manila apartment. In August 1996 the C106D was described at the Bojinka trial as Yousef’s “signature,” but in the spring of 1996 nobody outside the FBI or the SDNY prosecutor’s office had access to those details.

Scarpa Jr. also retrieved a schematic from Yousef that showed how a Casio DBC-61 Databank watch could be soldered into a C106D semi-conductor. That schematic matched copies of a Casio IED recovered from Yousef’s Manila apartment. In August 1996 the C106D was described at the Bojinka trial as Yousef’s “signature,” but in the spring of 1996 nobody outside the FBI or the SDNY prosecutor’s office had access to those details.

The FBI was impressed. They gave Greg Jr. a camera to photograph the notes. Eventually they set up a phony Mafia front company called Roma Corp. Convincing Yousef that Roma was manned by wiseguys, Scarpa Jr. encouraged him to call it from the pay phone on the ninth floor of the MCC. That way, the purported mobsters could patch him through to his people in New York and the Middle East. Instead of mafiosi, of course, the feds had special agents on the phone who tracked each call.

It was around this time that the feds recorded one international call by Yousef from the jail, in which he asked to speak to “Khalid.” The number was traced to Doha, Qatar, and the bureau rushed its Hostage Rescue Team there only to have KSM disappear with the help of a senior Qatari official. It was KSM’s second escape from the FBI and he was free once again to carry out his nephew Ramzi’s plot.

It was around this time that the feds recorded one international call by Yousef from the jail, in which he asked to speak to “Khalid.” The number was traced to Doha, Qatar, and the bureau rushed its Hostage Rescue Team there only to have KSM disappear with the help of a senior Qatari official. It was KSM’s second escape from the FBI and he was free once again to carry out his nephew Ramzi’s plot.

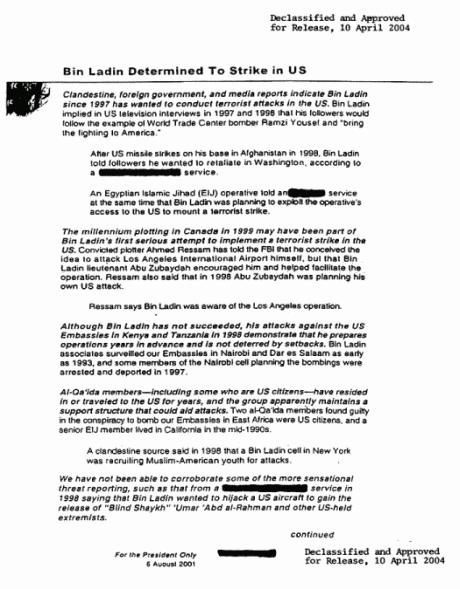

Over the course of 11 months, Greg Jr.’s Yousef sting yielded an amazing amount of intelligence—including proof of an active Al Qaeda cell in New York City and a plot to hijack planes to free blind Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman from federal lockup. That last piece of intelligence was significant enough that, although qualified as unverified, it later showed up in the infamous Presidential Daily Briefing to President Bush weeks before 9/11, headlined “Bin Ladin Determined to Strike in U.S.”

The revelation about an active Al Qaeda cell should have rocked the corridors of the FBI’s New York office. Why? Because after Fitzgerald’s conviction of Sheikh Omar in 1995, the conventional wisdom of the feds had been that they had eliminated the Islamic terror threat to New York.

The revelation about an active Al Qaeda cell should have rocked the corridors of the FBI’s New York office. Why? Because after Fitzgerald’s conviction of Sheikh Omar in 1995, the conventional wisdom of the feds had been that they had eliminated the Islamic terror threat to New York.

Before his arrest, Scarpa Jr. ran a marijuana syndicate on Staten Island. In jail, his proximity to the terrorists, his skills as a Mafia con man and his audacious willingness to work for the feds (like his murderous father) made him the perfect spy. Documented in dozens of FBI 302 memos, his reports became known as “the Scarpa materials.”

One 302 recounted how, for a payment of $2,500, Yousef was willing to set up a meeting “between one of [Yousef’s] people and one of Scarpa’s people [FBI] on the outside.” Such a meeting would have given the FBI a chance to penetrate a U.S.-based Al Qaeda cell linked to bin Laden and KSM five years before the 9/11 attacks.

“These 302s had extraordinary potential intelligence value to other agencies like the CIA and DIA,” said Lieutenant Colonel Anthony Shaffer. A Bronze Star recipient, Shaffer was a key official in Able Danger, the U.S. Army’s top-secret data-mining operation, in 2000. “After we found similar links between the blind sheikh’s New York cell, this intel might have helped us connect some major dots in the years leading up to 9/11.”

Who was privy to the Scarpa Jr. sting? Patrick Fitzgerald and a host of FBI and Justice Department officials. The 302 of March 7, 1996 documents how Greg Jr. was interviewed by Dietrich Snell, Valerie Caproni (chief of the criminal division in the U.S. attorney’s office for the Eastern District of New York) and Fitzgerald.

“That information from Greg Jr. was clearly credible,” said Scarpa Jr.’s former lawyer Larry Silverman, himself an ex-EDNY prosecutor. “I first heard the name Osama bin Laden from Greg Jr. after Yousef told him that name. And I want to emphasize that this information came forth in stages. That proves it was credible. If at any point the information was inaccurate, the government would have pulled the plug.”

Did the FBI ever act on Yousef’s offer to meet his cell members? Did the CIA and the Defense Intelligence Agency ever see those Yousef-to-Scarpa Jr. kites or the two-inch-thick pile of FBI 302s? It’s unlikely, because by late summer 1996 the feds were moving into containment mode.

As I see it, the Justice Department officials came to believe that if the younger Scarpa was found credible in his sting of Yousef, he’d be credible when he testified about the alleged corrupt relationship between his father and R. Lindley DeVecchio.

A senior FBI agent, DeVecchio was under investigation by the bureau for allegedly feeding information about organized crime to Scarpa Sr.

A senior FBI agent, DeVecchio was under investigation by the bureau for allegedly feeding information about organized crime to Scarpa Sr.

In the early 1990s, the suspected leaks to Scarpa had contributed to what became known as “the Colombo war.” The intra-family struggle left 10 people dead. A federal judge had warned that more than 60 Mafia prosecutions in the EDNY had the potential to “unravel” if the Scarpa Sr.-DeVecchio scandal continued to fester.

The feds turned their back on Scarpa Jr., actually taking the position that the intelligence documented in those 11 months of 302s was fabricated.

Patrick Fitzgerald was a leading proponent of this assertion. In a June 25, 1999 Affirmation that I’d gotten unsealed, he swore that “Scarpa’s effort at ‘cooperation’ was a scam in collusion with Yousef and others.”

Fitzgerald’s principal authority for his theory was John Napoli, a Gambino family wiseguy who arrived on the ninth floor of the MCC in December 1996.

But when I interviewed Napoli from his Texas prison in 2006 he denied he’d ever called the Scarpa materials a fabrication: “As far as my personally being there, hearing it, seeing it—anything that Yousef gave Greg wasn’t a scam,” said Napoli. “It wasn’t a hoax. He wasn’t trying to do anything with Ramzi against the government. He was legitimately trying to help them. He was giving them information.”

Fitzgerald alleged collusion between the wiseguy and the terrorist, but he offered no explanation for why Yousef, then on trial, would knowingly reveal his secrets to the feds. Or how Scarpa Jr., a mobster with a 10th-grade education, could concoct such elaborate bomb schematics.

It didn’t seem to matter. By 1997 the hoax story stuck. When Greg Jr. sought reduced time a year later in return for his Yousef sting, the feds threw the book at him. The judge in his RICO trial sentenced Junior to 40 years in the Supermax prison even though he hadn’t been convicted of a single murder.

The FBI closed its two-year investigation of Lin DeVecchio and let him retire with a full pension (despite the fact that the ex-supervisory special agent had taken the Fifth Amendment, refused a polygraph and later, after a grant of immunity, answered “I don’t recall” more than 60 times when questioned on charges that he had leaked FBI intel to Scarpa Sr.).

The Brooklyn DA eventually indicted DeVecchio on four counts of homicide, leading to the mob scene outside the Brooklyn Supreme Courthouse in 2006. Following a two-week trial in the fall of 2007, the charges were dropped when a key witness was accused of perjury. Still, the presiding judge called DeVecchio’s relationship with Greg Sr. a “deal with the devil.”

Leslie Crocker-Snyder, a special DA appointed to investigate, concluded that there was no perjury. She also found that the alliance between the G-man and the hitman exposed “a dramatic picture of corruption” that “warrants further investigation.”

As I describe in Triple Cross, Patrick Fitzgerald had gone along with a decision by the feds to discredit important Al Qaeda intelligence.

But here’s the irony: The Twin Towers might still be standing if the feds had monitored an Al Qaeda hot spot in New Jersey. During the 1980s and early 1990s the “top investigative priority” in the FBI’s New York office was taking down mob boss John Gotti. The probe cost millions. But, following three failed conviction attempts, the feds finally brought down the Teflon Don with their around-the-clock surveillance of his Little Italy social club.

Meanwhile, across the Hudson River in Jersey City an Al Qaeda hot spot called Sphinx Trading went virtually ignored. A check-cashing and mailbox store, Sphinx pops up three times in the story of 9/11:

Meanwhile, across the Hudson River in Jersey City an Al Qaeda hot spot called Sphinx Trading went virtually ignored. A check-cashing and mailbox store, Sphinx pops up three times in the story of 9/11:

As early as 1991, the FBI had known that Sphinx was the location of a mailbox held by El Sayyid Nosair, an Al Qaeda cell member who had gunned down Rabbi Meir Kahane in 1990. While preparing to prosecute Sheikh Omar Rahman in 1994, Fitzgerald put Waleed al-Noor, the co-incorporator of Sphinx, on a list of 172 unindicted co-conspirators (Osama bin Laden was also among them).

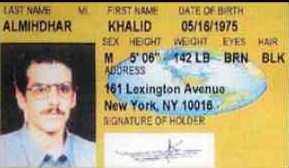

In fact, Rahman preached at a mosque in a building just a few doors down from the store. And in July 2001, two of the 19 9/11 hijackers obtained their fake IDs from Mohammed El-Attris, the other co-incorporator of Sphinx Trading (where the pair rented mailboxes). They contained a bogus Lexington Avenue address.

In the face of the evidence, you have to ask whether the feds could have interdicted the 9/11 plot if they’d devoted half the surveillance time they’d put in on John Gotti to the building on Kennedy Boulevard that once housed “the Jersey jihad office.”

In the face of the evidence, you have to ask whether the feds could have interdicted the 9/11 plot if they’d devoted half the surveillance time they’d put in on John Gotti to the building on Kennedy Boulevard that once housed “the Jersey jihad office.”

In September 2008, with a third letter to HarperCollins, Fitzgerald amped up the pressure to make sure my book would never appear in paperback: “I write to demand immediate compliance with my demands of October 2007,” he insisted. “Surely HarperCollins can make a decision in a year.” Months later, the publisher did. HarperCollins came down on the side of the First Amendment and an investigative reporter’s right to tell a story, no matter how embarrassing a public official might find it. The updated edition of Triple Cross is due on June 16.

About the Author

A five-time Emmy Award-winning investigative reporter and former correspondent for ABC News, Peter Lance is the author of 1000 Years for Revenge, Cover Up and the novel First Degree Burn. Buy the new paperback edition of Triple Cross at Amazon.com.

Seven weeks ago Patrick Fitzgerald, the most intimidating Federal prosecutor in America, sent my publisher (HarperCollins) and me a letter threatening to sue us for libel if Triple Cross, a book I wrote, critical of his anti-terrorism track record, was published.

Yesterday marked the four-week anniversary of the book’s pub date and although it’s been out for a month, we’re still waiting for his summons and complaint.

It was the fourth threat letter that Fitzgerald had sent since October 2007 and the man who’d succeeded in getting New York Times reporter Judith Miller jailed for 85 days in the CIA leak probe was growing impatient.

“To put it plain and simple,” Fitzgerald wrote, “if in fact you publish the book this month and it defames me or casts me in a false light, HarperCollins will be sued.”

You could almost hear Fitzgerald holding his breath and stamping his feet, astonished that we had not rolled over after he issued the following demand in his first letter 20 months earlier: For full Post CLICK IMAGE

I write to demand that Harper Collins cease publication, distribution and sale of the current version of the book… issue and publish a clear and unequivocal statement acknowledging that the book contains false statements about me; refrain from publication of any updated version (and) take no steps to transfer the rights to any other person or entity to publish the book in any form.

In this initial letter, Fitzgerald included an attachment requesting that HarperCollins “preserve” twelve separate categories of records including all “book drafts,” correspondence between me and the publisher, even “records of any and all projected sales” of the book “including any and all records of profits attributable to Triple Cross.”

There was even the hint of a personal vendetta. Apparently, Judith Regan, my former publisher, who’d left HarperCollins in 2006 after the scandal over the O.J. Simpson book If I Did It had discussed a $1 million book deal with Fitzgerald for his memoirs.

So in that first threat letter, the U.S. Attorney demanded:

…any documents reflecting Harper Collins estimate of the market value of my personal reputation, including, but not limited to, any documents relating to an unsolicited letter from Judith Regan, on behalf of Harper Collins, to me offering me a “seven figure” sum for the rights.

Two weeks later, on November 2nd, 2007, Mark Jackson, then attorney for HarperCollins, rejected Fitzgerald’s libel claim and called Triple Cross “an important work of investigative journalism.”

But the man The Washington Post once called a “relentless” prosecutor was undaunted. On November 16th, Fitzgerald send a second letter; this one amounting to 16 pages. And, as if to remind us who we were dealing with, each page bore a time stamp showing that it was faxed from the office of the “U.S. Attorney Chicago.”

In the June 8th edition of Newsweek, when Michael Isikoff, broke the story of Fitzgerald’s campaign to kill the book, he quoted the Chicago U.S. attorney as saying that he was “not aware” that the time stamp would be visible. But that’s a difficult story to swallow from the man Vanity Fair described as having a “mainframe-computer brain,” in their fawning 2006 tribute, “Mr. Fitz Goes to Washington.”

32 Pages of Threat Letters

If you go to my website http://peterlance.com and download the 32 pages of threat letters, they chronicle an almost obsessive effort by Fitzgerald to pulp the book.

In his third letter, sent on September 22nd, 2008 Fitzgerald actually used the word “demand” twice in the same sentence: “I write to demand immediate compliance with my demands of October, 2007.”

In his fourth letter, sent June 2nd, 2009, Fitzgerald described the entire book as “a deliberate lie masquerading as the truth.”

Consider the recklessness of that statement in the context of the libel standard that all journalists live by: the rule set forth in the landmark Supreme Court case, New York Times vs. Sullivan.

In order to mount a successful defamation claim “Times vs. Sullivan” requires a public official like Fitzgerald to demonstrate “a reckless disregard for the truth,” or “actual malice.”

Fitzgerald would be hard pressed to clear that hurdle, since the hardcover edition of Triple Cross ran 604 pages, with 1,420 end notes and 32 pages of documentary appendices including a series of FBI 302 memos and a 1999 affirmation sworn to by Fitzgerald himself.

If you have any doubts about the depth of my research, termed “meticulous” in a recent piece for Forbes.com, you can download a pdf of the illustrated Timeline from the middle of the book, along with those appendices, which include some heretofore classified documents.

Yet in his 20-month campaign to kill the book, Fitzgerald crossed the threshold of libel himself. In a June 8th interview with the Associated Press, he falsely claimed that I blamed him in Triple Cross for the mass casualties on 9/11 and the African Embassy bombings:

“The book lied about the facts and alleged that I deliberately misled the courts and the public in ways that in part caused the deaths in the 1998 embassy bombing attacks and in the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.” Fitzgerald said the lives lost in those attacks were personal for him and he decided to stand up for himself because “it is outrageous to falsely accuse me of causing those deaths corruptly.”

A simple reading of Triple Cross in its hardcover edition will offer proof positive that I never even came close to making such a claim. But that comment, along with Fitzgerald’s “lie masquerading as the truth” line, suggested the same reckless disregard for the truth that Iwas accused of by the Chicago U.S. Attorney.

A Justice Dept. Complaint Vs. Fitzgerald

So, on June 15th, I filed a complaint against Fitzgerald with the Justice Department’s Office of Professional Responsibility, asking acting counsel Mary Patrice Brown to open what amounts to an internal affairs investigation of the U.S. Attorney and his drive to pulp my book.

An examination of Fitzgerald’s 32 pages of threat letters suggests that if he actually wrote them himself he must have spent days, perhaps even weeks, trying to bury Triple Cross. If he used one of the 161 lawyers in the Chicago federal prosecutor’s office, that raises even more serious questions.

Since word of the Fitzgerald censorship scandal broke I’ve had the support of a number of First Amendment and anti-censorship advocates. including The Reporter’s Committee for Freedom of the Press, Nat Hentoff, the éminence gris of The Village Voice and Jan Schlichtmann, the gusty tort lawyer celebrated in Jonathan Harr’s 1995 best seller A Civil Action.

“What Patrick Fitzgerald, tried to do, in attempting to shut down this book, was repugnant,” says Schlitchtmann. “It represented a virtually unprecedented attempt by a sitting U.S. official to kill a book critical of his performance in office. Fitzgerald had to know he didn’t have a libel claim, yet for months and months he tried to force HarperCollins and Peter Lance to knuckle under to his demands — something they refused to do.”

So far, online columnists on the right and the left, who might otherwise have cut each other’s throats, have been universal in their support for Triple Cross’s publication.

See columns from Newsmax, WorldNetDaily, Accuracy in Media and The New American on the right to The Daily Kos, rawstory.com and thepublicrecord.com on the left.

Rory O’Connor’s piece for The Huffington Post was entitled: Patrick Fitzgerald’s Private Jihad.

MY HUFF POST

MY HUFF POST

Recent Comments